calsfoundation@cals.org

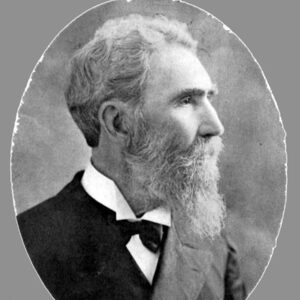

James Philip Eagle (1837–1904)

Sixteenth Governor (1889–1893)

James Philip Eagle served as governor during one of the most turbulent times in Arkansas’s history. Elected under a cloud of election fraud and faced with a divided Democratic Party, he presided over a General Assembly bent on enacting a series of “Jim Crow” laws to segregate Arkansas society along racial lines. By the time Eagle left office, the dominance of the Democratic Party had been restored, but Arkansans were more racially divided than at any time since the days of slavery.

James Eagle was born on August 10, 1837, in Maury County, Tennessee, the son of James and Charity Swaim Eagle. The family, of German descent, immigrated to the United States from Switzerland. In November 1839, Eagle’s father, a farmer, brought his family to Arkansas and purchased a farm in Pulaski County. In 1857, the family moved to the Richwoods community in what was then Prairie County (today, the community would be located near Lonoke in Lonoke County).

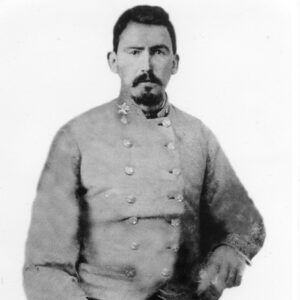

In 1859, Eagle was appointed deputy sheriff of Prairie County. He held that position until the Civil War. In June 1861, he enlisted as a private in the Fifth Arkansas Mounted Regiment and was assigned to Confederate units in Indian Territory; he was soon transferred to the Second Arkansas Mounted Riflemen, which was later made a part of the First Consolidated Arkansas Mounted Rifles. He also saw action in Kentucky and Tennessee, where he was taken prisoner. Released in a prisoner exchange in May 1863, he rejoined his old unit and participated in battles in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Georgia. In the Battle of Atlanta, he received a severe abdominal wound but recovered in time to rejoin his unit for campaigns in Tennessee and North Carolina. By the time the war was over, he had reached the rank of lieutenant colonel.

His father died during the war, and Eagle inherited most of his estate. He was able to build on his father’s holdings and became one of the most prosperous farmers in central Arkansas. By the early 1880s, he owned 2,400 acres of farmland and fourteen lots in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Having converted to Christianity during the war, he joined the New Hope Baptist Church shortly after his return and was licensed to the ministry in 1870. As a Baptist minister, he needed more education, and in 1870, he enrolled at Mississippi College. Illness forced him to drop out of school before completing the first year. He returned to Arkansas, where he began to work with small, rural Baptist churches. He was elected president of the Arkansas Baptist State Convention for twenty-four consecutive years.

In 1872, he was elected to represent Arkansas, Prairie, and Lincoln counties in the General Assembly. He joined the legislature in the midst of the Brooks-Baxter War over the governor’s office. Eagle supported Elisha Baxter in the controversy, organized six companies of volunteer troops in response to Baxter’s call for protection, and served as one of the three commissioners appointed by the legislature to investigate claims growing out of the conflict. He also served as a delegate to the 1874 constitutional convention and continued to represent his district when the new constitution was adopted. Eagle introduced the bill to create Lonoke County and served as representative from that county in the twenty-second (1877–79) and twenty-fifth (1885–87) sessions of the General Assembly. During the latter session, he served as speaker of the house.

Between those sessions, on January 3, 1882, he married Mary Kavanaugh Oldham, originally from Kentucky, whom he had met during the Civil War. The couple had no children.

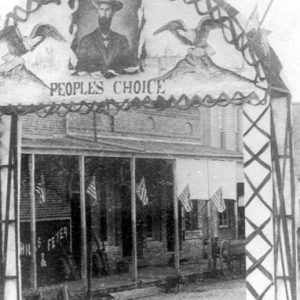

After repeated urging from supporters, Eagle sought the nomination for governor in 1888. The Democratic convention of that year was one of the most acrimonious in the party’s history. Five candidates appealed for support, and the meeting lasted three days. It took 126 ballots before the delegates chose Eagle as the party’s nominee. He won in the general election by an approximately 15,000-vote margin amid widespread charges of election fraud. As governor, he faced a divided party and a disorganized General Assembly. He demanded that the assembly appoint a special commission to investigate the fraud charges, but legislators refused. He urged the assembly to reform the prison system and to create an equalization commission to restructure tax rates. Legislators largely ignored Eagle’s requests, and for the balance of his first term, he spent most of his time trying to restore harmony in the party.

Eagle was a paradox. He owned one of the largest farming operations in Pulaski and Lonoke counties but, as governor, championed causes dear to small farmers and rural Arkansans. He also supported female suffrage and personally opposed many of the racially discriminatory bills introduced by legislators. Nevertheless, he signed them into law for the sake of party unity. He also welcomed Benjamin Harrison, the first sitting U.S. president to visit the state.

Efforts to reunify the Democratic Party were largely successful, and Eagle won reelection in 1890 by a comfortable margin. But a unified party did not mean a cooperative legislature, and Eagle faced most of the same obstacles in his second administration. The assembly still ignored most of his program, including a new call for a railroad commission, an equalization board, abolition of the convict-lease system used by the state prison system, and a new state penitentiary. Legislators were more interested in Jim Crow laws and followed their own agenda. Perhaps the most notorious of the laws that came out of this session was the “separate coach law,” which segregated public transportation and accommodations in the state. Eagle refused to endorse the proposal, but he did sign it into law. He also signed the Election Law of 1891, which ensured the dominance of the Democratic elite for decades to come.

He did not seek a third term for governor and retired from politics. He continued to live in Little Rock and remained active in Baptist church work. He also served on the first State Capitol Commission but was removed from that body by Governor Jeff Davis over what Eagle supporters said was a dispute involving church politics. Both men were members of Little Rock’s Second Baptist Church, and Eagle participated in a successful move by church leaders to exclude Davis from the church on charges of excessive alcohol consumption.

Eagle died of heart failure on December 20, 1904, in Little Rock and was buried at Mount Holly Cemetery.

For additional information:

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press,1995.

Graves, John William. Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban Context, Arkansas, 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press,1990.

James Philip Eagle Papers. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Moneyhon, Carl H. Arkansas and the New South, 1874–1929. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Niswonger, Richard L. Arkansas Democratic Politics, 1890–1920. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

C. Fred Williams

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Politics and Government

Politics and Government Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Eagle House

Eagle House  James Eagle

James Eagle  James Eagle

James Eagle  Mary Eagle

Mary Eagle  James Eagle Campaign Arch

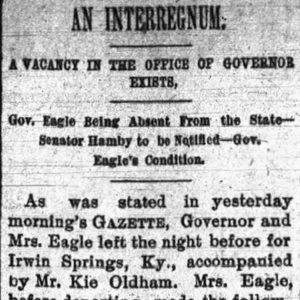

James Eagle Campaign Arch  Governor Vacancy Article

Governor Vacancy Article  Governor's Residence

Governor's Residence

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.