calsfoundation@cals.org

William Meade Fishback (1831–1903)

Seventeenth Governor (1893–1895)

William Meade Fishback was a prominent Unionist during the Civil War who became the seventeenth governor of Arkansas. He was elected (but not seated) as U.S. senator by the Unionist government in 1864. During Reconstruction, he became a Democrat and, in the mid-1870s and early 1880s, championed repudiation of state debts. The Fishback Amendment earned him the name the “Great Repudiator.” His relatively lackluster one term as governor was most notable for his public relations effort to improve Arkansas’s image.

William Fishback was born on November 5, 1831, in the Jeffersonton community of Culpeper County, Virginia, the oldest of the nine children born to Frederick Fishback and Sophia Ann (Yates) Fishback. As the son of a prosperous farmer, he received the rudiments of a classical education before attending the nearby University of Virginia. He taught school after his graduation in 1855, but he also read law in a Richmond law office. In 1857, he moved west to Springfield, Illinois, where he was admitted to the bar and came in contact with several other lawyers, including Abraham Lincoln, whose firm sent him his first client. Shortly after the conclusion of Lincoln’s famous 1858 debates with Stephen Douglas, Fishback moved to the frontier region of Sebastian County near Fort Smith.

Within a month of his arrival, he entered into a partnership with Judge Solomon F. Clark in nearby Greenwood (Sebastian County). The partnership flourished, but the crisis of the Civil War compelled the young attorney to become directly involved in public affairs. His Unionist stance led to his election as a Sebastian County delegate to the state convention considering secession, where he voted with the majority against it. However, during the second session of the Secession Convention, following the firing on Fort Sumter, he joined the majority endorsing secession, with Isaac Murphy left as the lone dissenter. Fishback’s rationale for this reversal was that President Lincoln’s policy of coercion would collapse because the departure of additional Southern states would result in practical persons in both sections demanding reunion. Armed hostilities in reaction to Fort Sumter caused him to journey to Missouri and take the oath of allegiance to the Union. Fishback then moved to St. Louis became editor of the St. Louis Democrat. In Missouri, he became involved in Unionist politics, and after Little Rock (Pulaski County) fell in 1863, General James Schofield appointed him a colonel with the responsibility of forming the Third Arkansas Infantry Regiment. Upon his return to Little Rock, he published a Unionist newspaper, the Unconditional Union, instead of recruiting for the Third Arkansas, but he later recruited 900 men for the Fourth Arkansas Cavalry.

Fishback did not actively serve in either unit. At one point, he was viewed as the leader of “the Fishback faction,” which included Isaac Murphy and Elisha Baxter. Their efforts were designed to not only meet Lincoln’s Ten Percent Plan but also to weaken the antebellum elite and make Arkansas government more democratic. Over the protests of some more moderate conservative Unionists, the group successfully called a constitutional convention to meet in January 1864. Fishback was instrumental in writing the Loyalist Constitution of 1864, referred to by some as “the Fishback Constitution.” One of the most controversial provisions restricted suffrage to whites, even as it abolished slavery; secession was voided, and several state offices were made elective. The convention chose Murphy as provisional governor and called for an election to approve its work and to elect a legislature. President Lincoln lauded the convention’s efforts and, in March, the requisite number of voters (at least ten percent of the 1860 electors) approved. Elisha Baxter and Fishback were chosen by the new legislature in May as the two U.S. senators from Arkansas, but in February 1865, their admission was denied by congressional Republicans displeased with Lincoln for trying to restore Southern representation in Congress so easily. Consequently, in the first several months after the war, Fishback served as a federal treasury agent, gaining some popularity among former foes by protecting numerous impoverished ex-Confederates from property seizures.

Fishback soon returned to Sebastian County, reopened a law office in Fort Smith, and spent the next decade building his practice into one of the most prosperous in western Arkansas. On April 4, 1867, he married Adelaide Miller, whose father had been a prominent Fort Smith merchant. They had six children. After his wife’s death on December 6, 1882, he never remarried.

Shortly after his marriage, Fishback had increased his vocal criticism of Reconstruction policies and eventually switched to the Democratic Party. Local Democrats selected him as a delegate to the 1874 constitutional convention. He gained considerable notoriety for his failed attempt to include a provision rejecting certain categories of state indebtedness. This stand, made at the convention and in the legislature after his election to the House of Representatives in 1876 and again in 1878, earned him the label the “Great Repudiator” throughout the state. He felt these categories of debt—the “Holford bonds,” the railroad aid, and the levee bonds—had been incurred without sufficient value accruing to Arkansas and, consequently, should be canceled. On April 2, 1879, the legislature finally passed the “Fishback Amendment” for presentation to the voters, but the measure was blocked by conservative governors Augustus Garland and William Miller until 1884. That year, this first amendment to the ten-year-old constitution passed overwhelmingly in the general election—119,806 to 15,492. Its passage prohibited the legislature from paying either principal or interest on the three categories of bonds and resulted in the “Great Repudiator” being hailed as the leader of those who had freed the state from as much as $14 million of questionable indebtedness.

The popularity of his amendment did not result in immediate political success for Fishback, partially because it hurt the state’s credit rating in the Northeast but especially because several influential conservative Democrats opposed repudiation. He received little support from Democratic convention delegates for the gubernatorial nomination in 1880 and 1888 or for the U.S. Senate in 1884, but finally on June 14, 1892, he was nominated for governor on the first ballot. In the campaign, he won an easy victory over his two principal opponents: the Republican William G. Whipple, a former mayor of Little Rock, and Jacob P. Carnahan, nominee from the newly formed Populist Party. Fishback was a veteran state-wide campaigner, unlike his opponents, and this was reflected in the September 5 vote: Fishback, 90,115; Whipple, 33,634; and Carnahan, 31,116, with all but seven counties carried by the Democratic candidate. Although the election of 1892 was conducted on a higher plane than some previous ones, it precluded the possibility of a two-party system. Further, the Election Law of 1891, with its literacy clause and the proposed poll tax amendment, boded ill for African-American voting participation. Before the election, twelve African Americans still sat in the legislature, but none remained afterward. White supremacy and Democratic primacy had become assured.

In his inaugural address on January 14, 1893, Fishback proclaimed that “it is not more laws that we need so much, but a broader development of the physical, social and intellectual resources with which our state has been so happily endowed.” Accordingly, he urged the legislature to make efforts to foster agricultural prosperity, physical resources development, public-education improvements, flood control, good roads, and the enhancement of Arkansas’s image. The last point led him to urge lawmakers to fully support an outstanding Arkansas exhibit at the Columbian Exposition of 1893. It is somewhat ironic that perhaps his principal contribution as governor was his attempt to portray Arkansas as a state with great potential for prosperity, even during the period when agrarian distress was rising as a result of the Panic of 1893. While the Arkansas exhibition won several awards at the exposition, it failed to attract the expected increase in desirable immigrants and industries. Nonetheless, throughout his term, Fishback focused his energies on public relations activities designed to help dispel the perception that Arkansas was still a wilderness peopled by ignorant squatters.

Fishback’s victory in the election never translated into a mandate acknowledged by legislators in the Twenty-ninth General Assembly and other major Democratic politicians. In particular, Senate president E. B. Kinsworthy and Attorney General James P. Clarke dealt with Fishback warily. The possibility of influencing the legislators and other officials was further diminished by his view that governments should be a limited force in society whenever possible. However, in 1894, he quite forcefully sent the state militia to Little Rock and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) rail yards to protect property during strikes resulting from the famous Pullman strike of that year. He also witnessed the negotiations with the federal government that resulted in the establishment of Fort Roots in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) in exchange for the cession of the old arsenal grounds in Little Rock. More importantly, he cooperated with the General Assembly in establishing the St. Francis Levee District, which covered over 1,500 square miles between Crowley’s Ridge and the Mississippi River and eventually reclaimed over a million acres for cultivation.

The national depression dampened Governor Fishback’s tenure. When he made a foolhardy attempt to take the Democratic senatorial nomination from the incumbent James Henderson Berry, while running for his own gubernatorial reelection in 1894, he lost both, with James P. Clarke easily becoming his successor. After his gubernatorial term, Fishback never again held public office, but he continued to participate in politics. In 1896, he was active in stumping the state for William Jennings Bryan and free silver, an issue he had derided in his own campaign just four years earlier but one that both he and his party came to embrace as a cure for the depression. He remained active in his law practice in Fort Smith until he suffered a stroke in early February 1903. He died in his sleep on February 9, 1903, and is buried in Oak Cemetery in Fort Smith.

For additional information:

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Herndon, Dallas T. Centennial History of Arkansas. vol. 1. Little Rock: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1922.

Moneyhon, Carl H. Arkansas and the New South: 1874–1929. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

———. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

Harry W. Readnour

University of Central Arkansas

This entry, originally published in The Governors of Arkansas, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. The Governors of Arkansas is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Walker, David

Walker, David Arkansas State Building

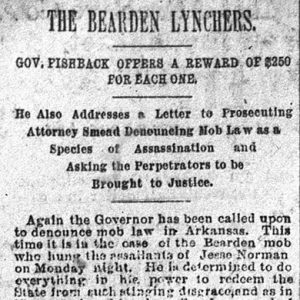

Arkansas State Building  Fishback Lynchings Letter

Fishback Lynchings Letter  William Fishback

William Fishback

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.