calsfoundation@cals.org

Gary v. Stevenson

The Arkansas State Supreme Court adjudicated Gary v. Stevenson, a freedom suit and racial-identity trial, in 1858. It was one of an increasing number of racial-identity suits in the South during the last decade before the Civil War. In this case, Thomas Gary sued slaveholder Remson Stevenson in an attempt to win his freedom from slavery. Gary, aged about sixteen in 1858, whom witnesses described as having sandy-colored hair and blue eyes, appeared to be white. He contended that he was lawfully free because he was the white son of white parents. Stevenson, a slaveholder in Van Buren (Crawford County), countered that Gary was the child of an enslaved mother and therefore not white; this made him a slave for life. The Crawford County circuit court ruled in Stevenson’s favor, and Gary appealed to the Supreme Court.

According to Gary, he was born in Alabama, where his parents cohabited until about 1843 when his father, also named Thomas Gary, left his mother to marry another woman. The elder Gary then sent his son to Louisiana under the care of a man named Armstrong until he would ask for his return. By a circuitous series of events, including Armstrong’s death, Gary was sold to Remson Stevenson of Crawford County, Arkansas, in 1850.

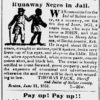

Witnesses testified that Stevenson purchased Gary from Riley Holman, who informed Stevenson that Gary’s mother was a slave but that Gary had been promised his freedom at age twenty-one. The sale was made with the understanding that Stevenson would indeed manumit Gary (that is, free him from slavery), but there was no legal obligation for him to do so. Gary lived with Stevenson until he ran away in May 1854, shortly after a court solicitor demanded that Stevenson hand him over to the elder Gary, who now claimed his son as his slave. Stevenson, fearful of losing a slave without recompense, attempted to sell Gary to a third party, Charles Bailey, instead. When Gary learned of those circumstances, he absconded, hoping to win his freedom in court. The court issued an injunction against all three claimants. Then, the elder Gary ceased pursuing the matter, and Bailey renounced any claim on the complainant, leaving Stevenson as the only defendant.

Arkansas law at the time defined a “Negro” as an individual with one-sixteenth “African blood.” Three medical doctors, presumed experts on determining race, testified about Gary’s ancestry. Two testified that Gary had no trace of African ancestry. The third concluded that it was possible he might have a small amount of “negro blood,” but not more than one-sixteenth.

Despite the experts’ opinions that Gary did not meet the state’s legal definition of “Negro,” the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled against Gary on the grounds that his mother was a slave, and therefore he was not white. Although Gary had claimed that his mother was a free white woman, the justices hinged their decision on the status of a woman named Susan, whom the justices concluded was Gary’s mother. Susan, like Gary, was fair skinned with straight hair, but she had never disputed her status as an enslaved woman. Moreover, her full lips and “coarse features” were deemed indicative of African ancestry. As the child of an enslaved woman, Gary inherited her status.

The Supreme Court’s decision also applied a version of the “one-drop rule” to determine racial status. Although many scholars consider the one-drop rule a product of the Jim Crow era, in the 1850s, the Arkansas Supreme Court applied a version of it in this case and in the similar Guy v. Daniel case. Despite Arkansas’s law defining “Negro” as having one-sixteenth African ancestry and medical testimony that Gary did not have a sufficient percentage of said ancestry, the Supreme Court ruled that he was not white simply because his presumed mother was a slave; by that logic, since a white person could not be a slave, Susan was not white, and consequently neither was Thomas Gary.

For additional information:

Clymer, Jeffory A. Family Money: Property, Race, and Literature in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Morris, Thomas D. Southern Slavery and the Law, 1619–1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Shafer, Robert. “White Persons Held to Racial Slavery in Antebellum Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Summer 1985): 134–155.

Warnke, Georgia. After Identity: Rethinking Race, Sex, and Gender. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Kevin D. Butler

University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff

African Americans

African Americans Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Law

Law Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Morrison v. White

Morrison v. White Slave Resistance

Slave Resistance

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.