calsfoundation@cals.org

Elaine Massacre of 1919

aka: Elaine Race Riot of 1919

aka: Elaine Race Massacre

The Elaine Massacre was by far the deadliest racial confrontation in Arkansas history and possibly the bloodiest racial conflict in the history of the United States. While its deepest roots lay in the state’s commitment to white supremacy, the events in and around Elaine (Phillips County) stemmed from tense race relations and growing concerns about labor unions. A shooting incident that occurred at a meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union escalated into mob violence on the part of the white people in Elaine and surrounding areas. Although the exact number is unknown, estimates of the number of African Americans killed by whites have ranged into the hundreds; five white people lost their lives.

The conflict began on the night of September 30, 1919, when approximately 100 African Americans, mostly sharecroppers on the plantations of white landowners, attended a meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America at a church in Hoop Spur (Phillips County), three miles north of Elaine. The purpose of the meeting, one of several by black sharecroppers in the Elaine area during the previous months, was to obtain better payments for their cotton crops from the white plantation owners who dominated the area during the Jim Crow era. Black sharecroppers were often exploited in their efforts to collect payment for their cotton crops. The union had contracted with lawyer Ulysses S. Bratton, whose son, Ocier, was at this meeting.

In previous months, racial conflict had occurred in numerous cities in America, including Washington DC; Chicago, Illinois; Knoxville, Tennessee; and Indianapolis, Indiana. With labor conflicts escalating throughout the country at the end of World War I, government and business interpreted the demands of labor increasingly as the work of foreign ideologies, such as Bolshevism, that threatened the foundation of the American economy. Thrown into this highly combustible mix was the return to the United States of black soldiers who often exhibited a less submissive attitude within the Jim Crow society around them.

Unions such as the Progressive Farmers represented a threat not only to the tenet of white supremacy but also to the basic concepts of capitalism. Although the United States was on the winning side of World War I, supporters of American capitalism found in communism a new menace to their security. With the success of the Russian Revolution, stopping the spread of international communism was seen as the duty of all loyal Americans. Arkansas governor Charles Hillman Brough told a St. Louis, Missouri, audience during the war that “there existed no twilight zone in American patriotism” and called Wisconsin senator Robert LaFollete, who opposed the war, a Bolshevik leader. During this “Red Scare,” the threat of “Bolshevism” seemed to be everywhere: not only in the labor strikes led by the radical Industrial Workers of the World but also in the cotton fields of Arkansas.

Leaders of the Hoop Spur union had placed armed guards around the church to prevent disruption of their meeting and intelligence gathering by white opponents. Though accounts of who fired the first shots are in sharp conflict, a shootout in front of the church on the night of September 30, 1919, between the armed black guards around the church and three individuals whose vehicle was parked in front of the church resulted in the death of W. A. Adkins, a white security officer for the Missouri-Pacific Railroad, and the wounding of Charles Pratt, Phillips County’s white deputy sheriff.

The next morning, the Phillips County sheriff sent out a posse to arrest those suspected of being involved in the shooting. Although the posse encountered minimal resistance from the black residents of the area around Elaine, the fear of African Americans, who outnumbered whites in this area of Phillips County by a ratio of ten to one, led an estimated 500 to 1,000 armed white people—mostly from the surrounding Arkansas counties but also from across the river in Mississippi—to travel to Elaine to put down what was characterized by them as an “insurrection.” On October 1, Phillips County authorities sent three telegrams to Gov. Brough, requesting that U.S. troops be sent to Elaine. Brough responded by gaining permission from the Department of War to send more than 500 battle-tested troops from Camp Pike, outside of Little Rock (Pulaski County).

After troops arrived in Elaine on the morning of October 2, 1919, the white mobs began to depart the area and return to their homes. The military placed several hundred African Americans in makeshift stockades until they could be questioned and vouched for by their white employers. (Union leader Robert Lee Hill was hidden by friends during the violence and later escaped to Kansas.) The violence even claimed those who had nothing to do with the union efforts, such as brothers David Augustine Elihue Johnston, Gibson Allen Johnston, Lewis Harrison (L. H.) Johnston, and Leroy Johnston, who were returning to Helena from a hunting trip when they were attacked and killed on October 2.

Evidence shows that the mobs of whites slaughtered African Americans in and around Elaine. For example, H. F. Smiddy, one of the white witnesses to the massacre, swore in an eye-witness account in 1921 that “several hundred of them… began to hunt negroes and shotting [sic] them as they came to them.” Anecdotal evidence also suggests that the troops from Camp Pike engaged in indiscriminate killing of African Americans in the area, which, if true, was a replication of past militia activity to put down perceived black revolts. In 1925, Sharpe Dunaway, an employee of the Arkansas Gazette, alleged that soldiers in Elaine had “committed one murder after another with all the calm deliberation in the world, either too heartless to realize the enormity of their crimes, or too drunk on moonshine to give a continental darn.”

Colonel Isaac Jenks, commander of the U.S. troops at Elaine, recorded the number of African Americans killed by U.S. troops as only two. In contrast, the correspondent for the Memphis Press on October 2, 1919, wrote, “Many Negroes are reported killed by the soldiers….” Other anecdotal information suggests that U.S. troops also engaged in torture of African Americans to make them confess and give information.

The white power structure in Phillips County formed a “Committee of Seven,” made of influential planters, businessmen, and elected officials, to investigate the cause of the disturbances. The committee met with Gov. Brough, who had ridden on the train with the troops and accompanied them on a march to the Hoop Spur area. The governor, who was reported as saying he was going to Elaine to “obtain correct information,” accepted the authority of the committee in return for its commitment that no lynchings would take place in Helena (Phillips County). He returned to Little Rock the next day and told a press conference, “The situation at Elaine has been well handled and is absolutely under control. There is no danger of any lynching…. The white citizens of the county deserve unstinting praise for their actions in preventing mob violence.”

From this point forward, two versions of what occurred at Elaine exist. The white leaders put forward their view that black residents had been about to revolt. E. M. Allen, a planter and real estate developer who became the spokesman for Phillips County’s white power structure, told the Helena World on October 7, “The present trouble with the Negroes in Phillips County is not a race riot. It is a deliberately planned insurrection of the Negroes against the whites directed by an organization known as the ‘Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America,’ established for the purpose of banding Negroes together for the killing of white people.”

On the other hand, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in New York, which had sent Field Secretary Walter White to investigate the events in Elaine, contested such allegations from the outset. White wrote in the Chicago Daily News on October 19, 1919, that the belief there had been an insurrection was “only a figment of the imagination of Arkansas whites and not based on fact.” He said, “White men in Helena told me that more than one hundred Negroes were killed.” Famed journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett secretly interviewed some of the prisoners in Helena, from which she produced the pamphlet “The Arkansas Race Riot.” This work also challenged allegations of an insurrection and documented the torture and other depredations the prisoners had suffered.

Within days of the initial shoot-out, 285 African Americans were taken from the temporary stockades to the jail in Helena, the county seat, although the jail had space for only forty-eight. Two white members of the Phillips County posse, T. K. Jones and H. F. Smiddy, stated in sworn affidavits in 1921 that they committed acts of torture at the Phillips County jail and named others who had also participated in the torture. On October 31, 1919, the Phillips County grand jury charged 122 African Americans with crimes stemming from the racial disturbances. The charges ranged from murder to nightriding, a charge akin to terroristic threatening (as defined by Act 112 of 1909). The trials began the next week, with John Elvis Miller leading the prosecution. White attorneys from Helena were appointed by Circuit Judge J. M. Jackson to represent the first twelve black men to go to trial. Attorney Jacob Fink, who was appointed to represent Frank Hicks, admitted to the jury that he had not interviewed any witnesses. He made no motion for a change of venue, nor did he challenge a single prospective juror, taking the first twelve called. By November 5, 1919, the first twelve black men given trials had been convicted of murder and sentenced to die in the electric chair. As a result, sixty-five others quickly entered plea-bargains and accepted sentences of up to twenty-one years for second-degree murder. Others had their charges dismissed or ultimately were not prosecuted.

In Little Rock and at the headquarters of the NAACP in New York, efforts began to fight the death sentences handed down in Helena, led in part by Scipio Africanus Jones, the leading black attorney of his era in Arkansas, and Edgar L. McHaney. Jones began to raise money in the black community in Little Rock for the defense of the “Elaine Twelve,” as the convicted men came to be known. The twelve men were: Frank Moore, Frank Hicks, Ed Hicks, Joe Knox, Paul Hall, Ed Coleman, Alfred Banks, Ed Ware, William Wordlaw, Albert Giles, Joe Fox, and John Martin.

At the same time, the New York offices of the NAACP, upon the advice of Arkansas attorney Ulysses S. Bratton, hired the Little Rock law firm of George Murphy, a former attorney general and candidate for governor, as counsel for the twelve men. Even at the age of seventy-nine, Murphy, a former Confederate officer and Arkansas attorney general, was considered one of the best trial attorneys in Arkansas. By late November, Jones was working with Murphy’s firm to save the Elaine Twelve.

Their initial task was to appeal the sentences given to the Elaine Twelve and ask for a new trial based on errors committed by the trial court. Gov. Brough issued a stay of the executions to permit an appeal to the Arkansas Supreme Court after the motions were denied. For the next five years, the cases of the Elaine Twelve were mired in litigation as Murphy and Jones fought to save the men from death. They secured new trials for six of the men, known as the Ware defendants, based on the fact that the trial judge had not required jurors to indicate the degree of murder on their ballot forms.The convictions of the other six men, known as the Moore defendants, were affirmed.

The cases of the Elaine Twelve were litigated on two separate tracks. The re-trials of the Ware defendants began on May 3, 1920. During the trials, Murphy became ill, and Jones became the principal counsel. Hostility toward him was so great from local white residents that, out of fear for his life, he was said to sleep at a different black family’s house every night during the trials. The convictions were again affirmed. Gov. Brough once again stayed their executions until the Arkansas Supreme Court could again review the cases. Ultimately, the Ware defendants were freed by the Arkansas Supreme Court after two terms of court had passed, and the state of Arkansas made no move to re-try the men.

The Moore defendants were granted a new hearing after the U.S. Supreme Court, in the case of Moore v. Dempsey, ruled that the original proceedings in Helena had been a “mask,” and that the state of Arkansas had not provided “a corrective process” that would have allowed the defendants to vindicate their constitutional right to due process of law on appeal.

Instead of pursuing a new hearing in federal court, in March 1923, Scipio Jones entered into negotiations to have the Moore defendants released. To be released, the men would have to plead guilty to second-degree murder and a sentence of five years from the date they were first incarcerated in the Arkansas State Penitentiary. Finally, on January 14, 1925, Governor Thomas McRae ordered the release of the Moore defendants by granting them indefinite furloughs after they had pleaded guilty to second-degree murder. In the interim, Jones had secured the release of the other Elaine defendants.

Though some local white residents of Phillips County still contend that white people at the time acted appropriately to prevent a slaughter in the Elaine area in 1919, the modern view of most historians of this crisis is that white mobs unjustifiably killed an undetermined number of African Americans. More controversial is the view that the military participated in the murder of blacks. Race relations in this area of Arkansas are currently quite strained for a number of reasons, including the events of 1919. A conference on the matter in Helena in 2000 resulted in no closure for the people in Phillips County. However, the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation provided major funding for a 2002 documentary, The Elaine Massacre: Tragedy and Triumph, which was distributed, along with an informational booklet, to every Arkansas school district. On September 29, 2019, a memorial to those who died during the massacre was dedicated in downtown Helena-West Helena. On November 5, 2019, the Elaine Twelve were memorialized on the Arkansas Civil Rights Heritage Trail in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Anthony, Steven. “The Elaine Riot of 1919: Race, Class, and Labor in the Arkansas Delta.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, 2019. Online at https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/2040/ (accessed November 9, 2022).

Burke, Jordan C. “White Discipline Black Rebellion: A History of American Race Riots from Emancipation to the War on Drugs.” PhD diss., University of New Hampshire, 2020. Online at https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2544/ (accessed November 9, 2022).

Butts, J. W., and Dorothy James. “The Underlying Causes of the Elaine Riot of 1919.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Spring 1961): 95–104.

Clancy, Sean. “Marking a Tragedy.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 29, 2019, pp. 1E, 6E.

Collins, Ann V. All Hell Broke Loose: American Race Riots from the Progressive Era through World War II. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2012.

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Dillard, Tom. “Scipio A. Jones.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Autumn 1972): 201–219.

Dunaway, L. S. What A Preacher Saw Through a Keyhole in Arkansas. Little Rock: Parke-Harper Publishing Company, 1925.

Elaine Race Massacre: Red Summer in Arkansas. UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture. https://ualrexhibits.org/elaine/ (accessed August 16, 2022).

Ellis, Mark. “J. Edgar Hoover and the ‘Red Summer’ of 1919.” Journal of American Studies 28 (April 1994): 39–59. Online at http://history.msu.edu/files/2010/04/Mark-Ellis.pdf (accessed August 16, 2022).

Ferguson, Bessie. “The Elaine Race Riot.” Master’s thesis, George Peabody College for Teachers (now Peabody College of Education and Human Development at Vanderbilt University), 1927.

Ives, Mike. “Beyond Tulsa, Overlooked Race Massacres Draw New Focus.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 29, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/29/us/elaine-massacre-history-lessons.html (accessed January 22, 2024).

Johnson, J. Chester. Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and a Story of Reconciliation. New York: Pegasus Books, 2020.

Krug, Teresa. “A Rural Town Confronts Its Buried History of Mass Killings of Black Americans.” The Guardian, August 18, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/aug/18/a-rural-town-confronts-its-buried-history-of-mass-killings-of-black-americans (accessed February 22, 2023).

Krugler, David F. 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Lancaster, Guy. “The Elaine Massacre and Memory: An Informed Polemic on Commemoration and Contestation Regarding the Nature of Atrocity.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 54 (August 2023): 130–139.

Lancaster, Guy, ed. The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Livingston, Kelly, and Madison Peek. “Two Narratives: How a 1919 Massacre Tore Elaine, Ark., Apart.” Howard Center for Investigative Journalism, November 15, 2021. https://lynching.cnsmaryland.org/2021/11/14/two-narratives-how-a-1919-massacre-tore-elaine-ark-apart/ (accessed August 16, 2022).

McCool, B. Boren. Union, Reaction, and Riot: The Biography of a Rural Race Riot. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1970.

McWhirter, Cameron. Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. New York: St. Martin’s, 2011.

Mitchell, Brian K. “Even in Tragedy, Memories Fail Us.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 21, 2024, p. 2H. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/jan/21/even-in-tragedy-memories-fail-us/ (accessed January 22, 2024).

———. “Soldiers and Veterans at the Elaine Massacre.” In The War at Home: Perspectives on the Arkansas Experience during World War I, edited by Mark K. Christ. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Mulder, Brandon. “Arkansas Residents Make a Case for Reparations 100 Years after the Elaine Massacre.” American Prospect, September 30, 2019. https://prospect.org/justice/arkansas-reparations-elaine-race-massacre/ (accessed August 16, 2022).

Pascal, Olivia. “Descendant of Arkansas’ Elaine Massacre Victims Push for Restorative Justice.” Facing South, October 7, 2020. https://www.facingsouth.org/2020/10/descendants-arkansas-elaine-massacre-victims-push-restorative-justice (accessed August 16, 2022).

Peacock, Leslie Newell. “To Those Known and Unknown: The Elaine Massacre Memorial.” Arkansas Times, August 2019, pp. 24–31. Online at https://arktimes.com/news/cover-stories/2019/08/02/to-those-known-and-unknown (accessed August 16, 2022).

Neuman, Scott. “In 2 U.S. Cities Haunted by Race Massacres, Facing the Past Is Painful and Divisive.” NPR, December 11, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/12/11/1137090651/elaine-massacre-tulsa-race-riot (accessed December 12, 2022).

Pierce, Michael, and Calvin White, eds. Race, Labor, and Violence in the Delta: Essays to Mark the Centennial of the Elaine Massacre. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

Research Materials for Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Race Massacres of 1919. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Roberts, Michael. “Elaine: A Premeditated Massacre.” MA thesis, Southern New Hampshire University, 2022.

Rogers, O. A., Jr. “The Elaine Race Riots of 1919.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 19 (Summer 1960): 142–150.

Smith, C. Calvin, ed. “The Elaine, Arkansas, Race Riots, 1919.” Special Issue. Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 32 (August 2001).

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Stockley, Grif, and Jeannie M. Whayne. “Federal Troops and the Elaine Massacres: A Colloquy.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 61 (Autumn 2002): 272–283.

Stopford, Annie. Trauma and Repair: Confronting Segregation and Violence in America. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2020.

Taylor, Kieran. “‘We Have Just Begun’: Black Organizing and White Response in the Arkansas Delta, 1919.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Autumn 1999): 265–284.

Visualizing the Red Summer. http://visualizingtheredsummer.com/ (accessed August 16, 2022).

Voogd, Jan. Race Riots and Resistance: The Red Summer of 1919. New York: Peter Lang, 2008.

Waskow, Arthur I. From Race Riot to Sit-in: 1919 to the 1960’s. New York: Anchor Books, 1967.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. “The Arkansas Race Riot.” N.p.: 1920. Online at https://archive.org/details/TheArkansasRaceRiot (accessed August 16, 2022).

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Black Farmers in the Red Autumn: A Review Essay.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 68 (Autumn 2009): 327–336.

———. “Low Villains and Wickedness in High Places: Race and Class in the Elaine Riots.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Autumn 1999): 285–313.

Whitaker, Robert. On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation. New York: Crown, 2008.

Williams, Lee E., and Lee E. Williams II. Anatomy of Four Race Riots: Racial Conflict in Knoxville, Elaine (Arkansas), Tulsa and Chicago, 1919–1921. Jackson: University and College Press of Mississippi, 1972.

Wise, Leah. “The Elaine Massacre.” Southern Exposure 1, nos. 3 and 4 (1974): 9–10. Online at https://www.facingsouth.org/1974/08/elaine-massacre (accessed January 30, 2024).

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Wormser, Richard, director. The Elaine Riot: Tragedy & Triumph. VHS Documentary. Little Rock: Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, 2002. Online at (part 1) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EM7XTg2tSDo and (part 2) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mD8ucOs4CKs (accessed January 22, 2024).

Grif Stockley

Butler Center for Arkansas Studies

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Army Trucks

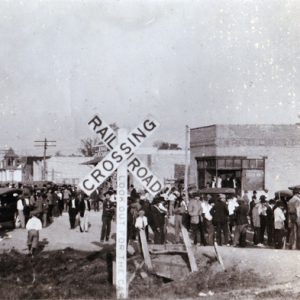

Army Trucks  Awaiting Arrival of Troops at Elaine Depot

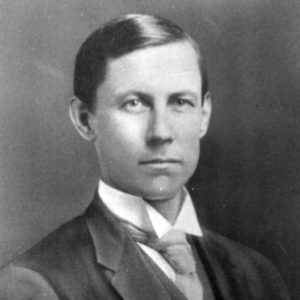

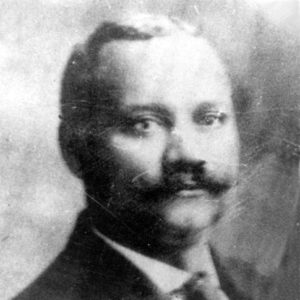

Awaiting Arrival of Troops at Elaine Depot  Ulysses S. Bratton

Ulysses S. Bratton  Charles Brough at Elaine

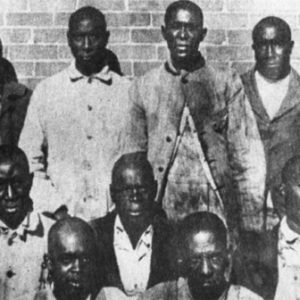

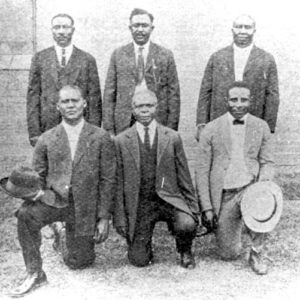

Charles Brough at Elaine  Elaine Massacre Defendants

Elaine Massacre Defendants  Elaine Massacre Newspaper Article

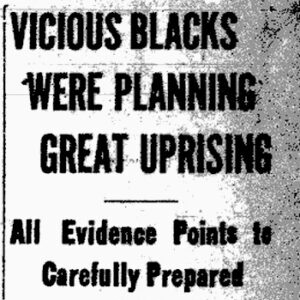

Elaine Massacre Newspaper Article  Elaine Massacre Newspaper Article

Elaine Massacre Newspaper Article  Elaine Machine Gun Emplacement

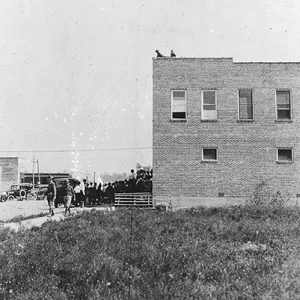

Elaine Machine Gun Emplacement  Elaine Temporary Stockade

Elaine Temporary Stockade  Elaine Massacre Aftermath

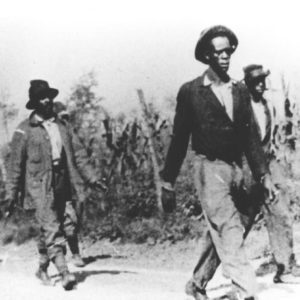

Elaine Massacre Aftermath  Elaine Massacre Defendants

Elaine Massacre Defendants  Elaine Massacre Flyer

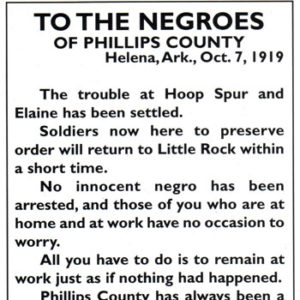

Elaine Massacre Flyer  Elaine Massacre Headlines

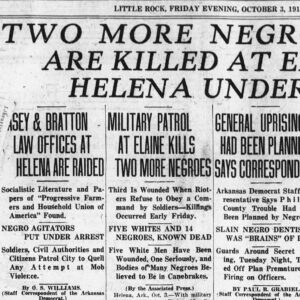

Elaine Massacre Headlines  Elaine Massacre Prisoners

Elaine Massacre Prisoners  Elaine Nurses

Elaine Nurses  Jacob Fink

Jacob Fink  Robert L. Hill

Robert L. Hill  D. A. E. Johnston

D. A. E. Johnston  Scipio Jones

Scipio Jones  Frank Moore Memorial

Frank Moore Memorial  Red Cross at Elaine

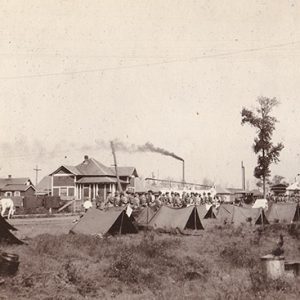

Red Cross at Elaine  Red Cross Canteen at Elaine

Red Cross Canteen at Elaine  Soldiers at Elaine

Soldiers at Elaine  Troops at Elaine

Troops at Elaine

I was born in Pope County, Arkansas, in 1955, thirty-six years after the Elaine Massacre. For the first five years of my education, I attended a Black school. I started sixth grade in a white school with only four Black students in the whole class. I regret to say that in both schools I was taught history but was never taught the true history of Arkansas. I remember buying food and having to sit or stand on the street to eat it. I stumbled onto the history of the Elaine Massacre while searching for my ancestry in 2021. I cried as I learned more about “Red Summer” and “Bloody Sunday.” My parents were born in 1924 and 1926, and I’m not sure that either of them knew exactly what happened in 1919–neither had an education higher than eighth grade. After finding information about the Elaine Massacre, I soon found that Elaine was not the only massacre. It’s not pretty and most want to forget it, but this is part of history and it should be remembered. It took what seemed like forever to find out how the African people were brought here as slaves and humiliated, raped, and whipped. I would love to hear more about the true history of the state of Arkansas–a place that was once called the Land of Opportunity but is now called the Natural State.

I first learned of the Elaine Massacre today, February 7, 2017, and I am both saddened and angered. My sadness comes from the senseless murder of human beings–so many that there isn’t an exact number, which is wrong on so many levels. How could anyone treat people with such horrendous disregard and violence? People often say they believe in God and that he doesn’t make mistakes, yet they refuse to acknowledge we are all created equal by him. So sad. My anger comes from this being hidden/erased from history like the lives that were taken that day. No one even took the time to “confirm the number of kills,” as if these people were as worthless as termites. That was 97 years ago but little has changed in the hearts of people. They still believe non-whites are a threat to their way of life. The fear is instilled by people who continue to voice the hatred of slave owners of 257 years ago and they don’t see it as the source of belligerent race rations. These are the same people who don’t understand why African Americans choose Black Lives Matter as a valid starting point. If we can’t get people to recognize we matter, we will never get past the color of our skin being the reason for unemployment, violence, and intolerance by authorities simply because we’re black. If we don’t teach ALL AMERICAN HISTORY we miss a opportunity to learn about our part, examine our present, and plan and prepare for our future as, ONE NATION, UNDER GOD, INDIVISIBLE, WITH LIBERTY AND JUSTICE FOR ALL.

During the 1910 census, my great-great-great-grandfather was listed. The 1920 census lists my great-great-great-grandmother as a widow. I have been trying to close a chapter in my family history. As you know, our black history is very limited in some areas. As for me, I have a timeline of ten years, 1910 to 1920, in the Delta of Bogy Township, Jefferson, Arkansas, just below Elaine, Arkansas. I am wondering if any group, agency, or government entity ever developed a list of the 100 or 237 black lynchings in 1919 in the Elaine area during that evil time in black history. Sandy Diggs or Toby Diggs was the name father and son, I’m trying to find what happened to them. Any information would be helpful. The information you have provided is great for families that lost people and is greatly needed. [Editor’s note: A professor at UA Little Rock is working to compile such a list.]

When I was a little girl, I remember my father, Willie Hall, receiving a letter from his uncle, Richard Hall, who was his father’s brother. Richard Hall asked my father to come to Mississippi to visit him. When my father arrived at the address that was on the letter, a lady answered the door, but she said his uncle didn’t live there. My mother said she believed his uncle Richard was there, but he was afraid to come outside for fear someone would be there to take him back to Arkansas. I know for a fact my father’s people were involved in the Elaine Riot. Paul Hall was one of the twelve men who were slated to be electrocuted, and I believe he was my relative.

What a travesty of justice. All the white people had to do was stay away from the church while the meeting was going on. This was murder on the part of the white population. The trials were a joke.