calsfoundation@cals.org

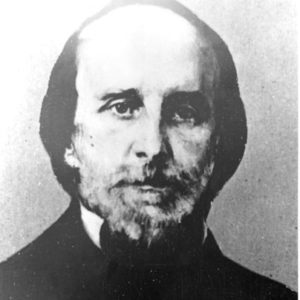

Isaac Murphy (1799–1882)

Eighth Governor (1864–1868)

Isaac Murphy was a teacher, attorney, and eighth governor of Arkansas. After years of relative obscurity, he became nationally famous when, at the Arkansas Secession Convention on May 6, 1861, he not only voted against secession but also resolutely refused to change his vote despite enormous crowd pressure. In 1864, he became the first elected governor of Union-controlled Arkansas.

Isaac Murphy was born outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on October 16, 1799, to Hugh Murphy and Jane Williams Murphy. His Murphy ancestors came to the United States from the Dublin, Ireland, area between about 1737 and 1740. His father was a paper manufacturer who died during Isaac’s childhood. The executor saw to Murphy’s education but squandered the estate before committing suicide. According to Murphy’s son-in-law, James R. Berry, Murphy graduated from Washington College in Washington, Pennsylvania, and was admitted to the Pennsylvania bar on April 29, 1825.

Murphy became primarily a schoolteacher, and moved to Clarksville, Tennessee, where he married Angelina Lockert on July 31, 1830. Murphy was her senior by fourteen years, and she was sixteen years old at the time of the marriage. Her father, a slaveholder, disowned her because of Murphy’s opposition to slavery. In 1834, shortly after the birth of their first daughter, the Murphys moved west to Fayetteville (Washington County), where Murphy surveyed land, occasionally practiced law, and taught school. He became chairman of the board of visitors to the Far West Seminary, a visionary educational institution located three miles northwest of Fayetteville promoted by former missionary and teacher to Native Americans, Cephas Washburn. Doubtless one reason for assigning Murphy this role was that he supported education, in spite of being a Democrat. Area Democrats fought the creation of the seminary, with six of the region’s Democrats voting in the state legislature against granting the school a charter. The Arkansas Gazette noted: “as they wish to keep their party in ascendancy, it is a principle with them never to encourage institutions of learning.” Despite a strong statement probably written by Murphy on the non-sectarian nature of the school, religious prejudice against Presbyterians figured in the fight as well. Democrats rejoiced when fire and hard times led to the project’s abandonment.

Murphy’s political career began in 1836 with his election as Washington County treasurer. He served until 1838. In 1846, he was elected to the lower house of the Sixth General Assembly. He was reelected in 1848. A Democrat staunchly opposed to the Arkansas political dynasty known as “The Family,” he introduced a bill to create a state-financed common school system, but it never made it out of committee. Astronomy was one of his main interests, and he made his own telescope using a horse collar.

Arkansas was hit hard by the failure of its banks, and Murphy (whose family, as enumerated in the 1850 census, consisted of Malilla, Romea, Louiza, Laura, Lockhart, and Geraldine) tried to repair his fortune by joining the exodus to the California gold fields apparently in 1849. While he was gone, in 1851, one of his notes was called in, and he lost his 120-acre farm. Murphy returned later that year, having failed to strike it rich. In 1854, he moved to Huntsville, the county seat of Madison County, and in 1856 was elected state senator, representing Madison and Benton counties in the Eleventh General Assembly. His wife died at their Huntsville home in 1860.

In February 1861, Murphy was elected on a Unionist platform to a state convention called to consider the issue of secession. At its March meeting, Murphy voted with the majority in refraining from taking any immediate action. The firing on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, however, led convention president David Walker to summon the delegates back to Little Rock (Pulaski County). On May 6, a motion Murphy supported to refer secession to the voters was turned down. Murphy was one of the five delegates who voted against the passage of the secession ordinance.

Walker then called for unanimity. Four delegates capitulated, but Murphy alone refused to budge. Several versions of his words have been put forward, but the essence was that he would not break his promise to the voters. Mrs. Frederick Trapnall of Little Rock showed her support by throwing him a bouquet from the gallery. Murphy remained in the convention until its work ended, living with a daughter and her husband (who subsequently enlisted and died in the Confederate service). He voted against Arkansas’s acceptance of the new Confederate Constitution, and he did not sign the new state constitution (Constitution of 1861) that concluded the convention’s work. After the convention adjourned, he returned to Huntsville, where he remained despite increasing threats on his life. After the Union invasion of Arkansas in the spring of 1862, he and two other avowed Unionists, James M. Johnson and his brother Frank, fled to General Samuel Curtis’s army in Missouri. Murphy joined Curtis’s staff as an aide, while Johnson raised the First Arkansas Infantry Volunteers. Murphy later managed to get his daughters out of Huntsville, but Louiza, age twenty-four, and Laura, age twenty-two, died along with the four-year-old child of a third daughter in St. Louis, Missouri, in early March 1863. Two other daughters, Geraldine and Angelina, were sent to a female seminary in Illinois.

Murphy, accompanied by his widowed daughter from Little Rock and her infant son, came back to the state capital with General Frederick Steele’s Union army in September 1863. Unionists began calling for reconstructing the state government, and Murphy’s name alone was mentioned as governor. In early 1864, a convention wrote a new constitution in which Murphy was declared to be the provisional governor until the March election. Murphy refused to act, but after the successful ratification in March, he was inaugurated on April 18, 1864. His inaugural address urged peace without rancor, and he used more than one third of his time to promote the necessity of education.

The Murphy government was a largely shadowy affair in that the Union army’s control barely extended a few miles outside of the few camps. Congressional leaders in Washington DC had already decried Abraham Lincoln’s Reconstruction plan and denied seating either the Arkansas congressmen or the two new U.S. senators (Elisha Baxter and William Meade Fishback) sent to Washington DC. Nevertheless, Congress considered the legislature valid to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery.

In the spring of 1865, the Confederacy collapsed. The Confederate state government disbanded, leaving Murphy alone in nominal control. While some diehard Confederates fled to Texas and then Mexico or Brazil, most came home. For the leaders, returning to public life and avoiding the loss of property required a pardon. Murphy was generous in recommending and expediting such requests, and his philosophy for Reconstruction paralleled that of some of his former allies, such as editor Christopher Columbus Danley at the newly revived Arkansas Gazette. However, in Rison v. Farr (1866), Chief Justice T. D. W. Yonley declared unconstitutional the test oath that banned from voting all those who had remained in rebellion after the establishment of the Union state government. In the next general elections in 1866, Unionist members were booted out of the legislature, and state auditor James Russell Berry, Murphy’s son-in-law, was left without a job. Murphy wielded his veto power in vain, but he did get a commitment for public education, although it was limited to whites. He also laid the foundations for accepting federal funds under the Morrill Act for a state institution of higher education, which Arkansas did not yet possess (this would become the University of Arkansas).

Unrepentant and utterly unreconstructed, the legislature thanked Jefferson Davis for his sterling conduct of the war and sent a delegation to Washington DC in support of the embattled and soon-to-be-impeached president, Andrew Johnson. Real power, however, had passed to Congress. The test case for admitting a reconstructed state to the Union was ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment. This amendment defined as citizens everyone born in the country and then extended to American citizens due process, equal protection of the laws, and the privileges and immunities of citizenship. Every Southern state except Tennessee rejected it, and each then fell under military control.

The situation in Arkansas was unique in that Murphy, an avowed Unionist, served as governor, and Unionists were present elsewhere in the government. Hence, Murphy was permitted to remain in office, and the state Supreme Court could continue its deliberations, but not those that touched on the rights of the freedmen. The former Confederate-dominated legislature, however, was sent packing.

Seeing an opening, former Union men, joined by a Northern element and leaders from the African American community, organized the Republican Party for the first time in Arkansas. In early 1868, they wrote a new constitution that was approved in a dubious election. New officials were chosen, but the whole scheme remained on hold until June 22, 1868, when Congress readmitted Arkansas to the Union. On July 2, Murphy turned over his office to the newly elected governor, former Union general Powell Clayton. Clayton arrived wearing white gloves, but the homespun departing governor took exception: “Only dudes wear gloves in the summer time,” Murphy exclaimed. Clayton took the gloves off and kept them off during his tumultuous term. After the swearing in, the men returned to the governor’s office in the capitol, where Murphy reached into a barrel and pulled forth a bottle of the highest quality (but untaxed) “mountain dew” for a toast.

Murphy returned home to Huntsville in 1868, where he farmed and practiced law. On occasion, he was called upon to be special judge when the presiding judge had a conflict of interest. Murphy died on September 8, 1882. He is buried in the Huntsville cemetery. Ironically, his house site later became the retirement home of segregationist governor Orval Faubus.

In a letter to Reverend Lyman Abbott in 1865, Murphy had laid out his vision of a new Arkansas. After declaring that “Industry, Education and Christian morality are the pillars of freedom,” he averred: “Kindness will conquer the most stubborn and reform if reform is possible.” Murphy was held in high regard during his gubernatorial days, and though denigrated by historian Thomas S. Staples, Murphy was better described by David Yancey Thomas as “a man of sound common sense, of good intentions, and of scrupulous honesty.”

For additional information:

Carter, Dean G. “Some Historical Notes on Far West Seminary.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Winter 1970): 345–360.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Isaac Murphy Papers. Kie Oldham Collection. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Moneyhon, Carl. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Smith, John I. The Courage of a Southern Unionist: A Biography of Isaac Murphy, Governor of Arkansas, 1864–68. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1979.

Staples, Thomas S. Reconstruction in Arkansas, 1862–1874. New York: Columbia University Press, 1923.

Todd, Keith J. L. “Forging with Embers: The Life and Pre-Gubernatorial Career of Isaac Murphy, 1799–1864.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2018. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3065/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Politics and Government

Politics and Government Isaac Murphy

Isaac Murphy

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.