calsfoundation@cals.org

Sanford Lewis (Lynching of)

At midnight on March 23, 1912, a mob hanged Sanford Lewis from a trolley pole in Fort Smith (Sebastian County). He had been suspected of shooting Deputy Constable Andy Carr, who sustained a fatal wound above the eye. Although the Arkansas Gazette refers to this as the first lynching in Sebastian County, it was actually the first lynching of an African American there. The murder of a white man named James Murray in the county on December 6, 1897, was described in many media outlets as a lynching.

Deputy Constable Andy Carr was probably the Andy Care [sic] listed on the census as living in Ward 4 in Fort Smith in 1910. Living with him were his wife, Della, and five children, ages eight to sixteen.

Some newspaper accounts report that Sanford Lewis was the son of a minister from Moffett, Oklahoma. (Moffett is located across the Arkansas River from Fort Smith in Sequoyah County, Oklahoma.) At the time of the 1910 census, farmer Webster Lewis was living in Sequoyah County with his wife, Lula. They had a son, named Lanford Lewis in the census but probably the same man as Sanford Lewis, and four other children.

According to initial reports in the Arkansas Gazette, the original incident was a complicated one. On the night of March 23, 1912, detectives Cathey Pitcock and J. O. Jarnigan had arrested several African-American men and women for disturbing the peace at the corner of 10th and Garrison streets. One man escaped and was pursued by Pitcock, Carr, and John Williams, who was identified as a “local horse trader.” Although there is no other information about Pitcock and Jarnigan, in 1910 Jonathan B. Williams, a native of Kansas, was living with his wife and two children and working as a horse buyer in Fort Smith.

Pitcock fired at the escaping man several times but missed. He then gave the gun to Williams, who chased Lewis to the Pony Express office at 10th and A streets and knocked him down. Lewis again escaped, but before Williams could resume the chase, he heard a shot and saw that Carr was down. Williams then beat Lewis until Officer Lacey arrived, whereupon he turned Lewis over to Lacey and took Carr to the hospital.

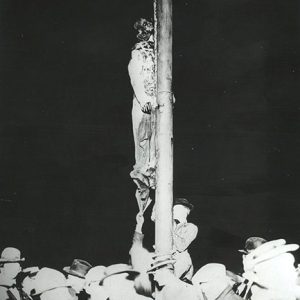

Lacey, followed by a large crowd, took Lewis to the jail. A mob of almost 1,000 people gathered in front of the jail and spent over an hour trying to break down the door. The police officers reportedly stood by while this was happening. Failing to break down the door, members of the mob pried off the bars on a window, and six men crawled through into the jail. They found Lewis hiding in a dark corner of his cell, reportedly “on his knees and pleading for mercy.” The men pushed Lewis through the window, and he was beaten. Mob members got a rope and took Lewis across the courthouse lawn onto Garrison Avenue. By the time they reached a trolley pole there, Lewis had been jumped on and kicked so many times that he was a “bleeding mess.” The Gazette reported: “Half dead, but yet pleading for mercy, he was strung up to a cross arm while the frenzied mob cheered.”

Some residents of Fort Smith were outraged that authorities had made no attempt to stop the mob. Mayor Fagan Bourland criticized the police department, saying that he himself “could have stopped the mob with three men,” and questioned the evidence in the case. No one involved in the incident saw Lewis with a knife, and the only revolver found at the scene belonged to Carr. Coroner Hugh Johnston scheduled an inquest to determine whether Lewis had fired the shot or whether Carr was accidentally hit by a stray bullet. Circuit judge Daniel Hon promised to call a special court session to prosecute the perpetrators.

On March 26, the Gazette reported that the grand jury had met. The grand jury heard from two eyewitnesses: J. F. Brewer and William Walker. Although their testimony was not public, they reportedly testified that Lewis did not shoot Carr. Hon told the grand jury members that they did not need to know the identities of mob members to return indictments and asked them to “secure a description of the lynchers for the assistance of the arresting officers.”

In the meantime, the city council had suspended Chief of Police Bryant L. Barry—as well as the night captain Sam Smart, chief of detectives Pitcock, and night jailer J. S. Stansberry—for their inaction when the mob attacked the jail. The council also vowed to find out why members of the police department failed to respond to orders to “save the negro by drenching the mob.” At a meeting of citizens called by President C. A. Lick of the Commercial League, fifty of Fort Smith’s most prominent citizens pledged funds to help prosecute mob members and condemned the lynching as an “outrage against law and order perpetrated by an irresponsible mob of thugs.” More than 1,000 Fort Smith citizens attended a public meeting to condemn the lynching and adopted a resolution asking citizens to help local officials and the grand jury to identify and convict the members of the mob. They also declared that any official who knew about the mob and failed to suppress it “deserves severest condemnation and is to be no longer trusted with public service.” By that time, the grand jury had heard testimony from nineteen witnesses but had failed to issue any indictments.

On March 28, John C. Stowers was arrested and charged with first-degree murder for leading the mob. (In 1910, thirty-seven-year-old Stowers was living in Fort Smith with his wife and two daughters and working as a carpenter.) A short time later, authorities arrested and jailed gambler Sam Smith as an “accessory before the fact of the crime of murder” for demanding the keys from the jailer. According to excerpts from the Southwest American, Smith had a record of petty larceny and vagrancy, and his brother, Walter, had served a term in the penitentiary for forgery.

Andy Carr died of his wounds around April 1 and was buried in Oak Cemetery in Fort Smith. Around that time, the city dismissed Barry and Smart for “lack of executive ability.” A number of other police officers—Pitcock, Jarnigan, Edward Pennewell, Laster, Surratt, Philips, R. O. Lacy, and Adams—were dismissed for “indifference, of lack of knowledge of what constituted the duty of an officer.” Little is known about these men. There was one Laster family in Fort Smith in 1910. Included in the household was the father, Frank Laster, and two sons, Dailey (born 1887) and Donald (born 1891). Although there were no Surratts listed in Fort Smith in 1910, E. H. Surratt and his wife were living there in 1900. By 1910, they were living in Van Buren in neighboring Crawford County, where they remained in 1920. There was a Robert Lacy living in Fort Smith in 1910 with his wife, Olive, and their two daughters and two sons. Thirty-five-year-old police officer Sam Smart was also there with his wife, Emma, and two children.

By early May, the grand jury had finished its work. According to the Gazette, the grand jury’s task had not been an easy one because “citizens and officers who undoubtedly are in a position to throw much light upon the identity of the mob members suffered from loss of memory,” and that there appeared to be “a general undercurrent to suppress evidence.” Despite these problems, they issued twenty-three indictments against fifteen people. John B. Williams was charged with involuntary manslaughter for killing Andy Carr, and also with assault for beating Lewis. John C. Stowers, who had been arrested but then released from jail, was indicted for first-degree murder for his role in the lynching and taken back into custody. Con Sullivan of Oklahoma was also charged with first-degree murder. Sullivan was apparently a seasoned criminal. In February 1905, he had appeared in court in Muskogee, Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), on charges of disturbing the peace, carrying a weapon, and assault with intent to kill. Two years later, the criminal docket there showed a second appearance, this time for introducing and disposing of liquor, committing forgery, and wearing a weapon. In early May 1912, he was accused with Lee Phillips in Van Buren of robbing a bank in Midland, but they were released for lack of evidence. Eight police officers were also indicted.

In a somewhat contradictory story written in June 1912, the Kenna Record reported that officers Lacey, Pennewell, and Jarnigan had been convicted of malfeasance in office by the circuit court. The story later indicates that five police officers in all had been indicted by the grand jury, tried, found guilty, and fined $100. By mid-August, Stowers was on trial in Waldron (Scott County). John B. Williams was tried soon after. After deliberating for twenty-seven hours, the jury acquitted Stowers; Williams was also acquitted. There is no indication as to whether Sam Smith and Con Sullivan were ever tried.

Officers Pennewell, Lacey, and Jarnigan appealed their convictions to the circuit court, and the case eventually was appealed to the Arkansas Supreme Court. On September 30, 1912, the Supreme Court upheld the original sentence, maintaining that the officers had clearly heard the threats of lynching but left the jail to go “on about their duties to other parts of the city,” making no effort to disperse the mob.

It is possible to trace the lives of some of those affected by the Lewis lynching. The Lewis family apparently left Oklahoma, and in 1920 they were living in Kansas City, Missouri. John B. Williams remained in Fort Smith, where by 1930 he was the Sebastian County sheriff. According to one source, he served as the county sheriff from January 1, 1929, until December 31, 1934, and died in 1966. In his Centennial History of Arkansas, Dallas Herndon reported that Williams “fairly radiates happiness and cheer and is a most likable man.” Con Sullivan continued his nefarious ways. In June 1923, Sullivan, described as “a wealthy gambler of Tulsa and Fort Smith, Ark.,” was arrested along with an attorney named Walter Chitwood for possessing a large number of Argentine government bonds, part of $3 million in bonds stolen in New York in April.

For additional information:

“23 Indictments Follow Lynching.” Arkansas Gazette, May 3, 1912, p. 1.

“Alleged Lynchers on Trial at Waldron.” Arkansas Gazette, August 14, 1912, p. 2.

Arkansas Reports: Cases Determined in the Supreme Court of Arkansas, Vol. 105. Little Rock: Democrat Printing & Lithographing Co., 1913.

“Arrest Alleged Leader of Mob.” Arkansas Gazette, March 29, 1912, p. 1.

Boulden, Ben. “The Lynching of Sanford Lewis.” Fort Smith Historical Society. http://www.fortsmithhistory.org/archive/lynchingSL.html (accessed October 13, 2020).

“Condemn Fort Smith Lynching.” Arkansas Gazette, March 27, 1912, p. 1.

“Dismissed Ft. Smith Officers.” Laclede Blade (Laclede, Missouri), April 5, 1912, p. 2.

“The February Term of Court.” Muskogee Daily Phoenix (Muskogee, Indian Territory), February 5, 1905, p. 2.

Hendricks, Wincie. “1912 Newspapers.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 36 (April 2012): 37–40.

Herndon, Dallas Turner. Centennial History of Arkansas, Vol. 3. Little Rock: S. J. Clarke Publishing 1922.

“Negro Victim of Fort Smith Mob.” Arkansas Gazette, March 24, 1912, p. 1.

“Police Held for a Lynching.” Kenna Record (Kenna, New Mexico), June 21, 1912, p. 8.

“Probing Fort Smith Lynching.” Arkansas Gazette, March 26, 1912, 1.

“Sanford Lewis’ Murder Brings Two to Prison.” Arkansas Gazette, March 29, 1912 , p. 1.

“Stowers Freed of Lynching Charge.” Arkansas Gazette, August 17, 1912, p. 1.

“To Probe Fort Smith Lynching.” Arkansas Gazette, March 25, 1912, p. 1.

Untitled. Muskogee Times-Democrat, February 4, 1907, p. 2.

Untitled. Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 22, 1923, p. 2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Lewis Lynching Article

Lewis Lynching Article  Sanford Lewis Lynching

Sanford Lewis Lynching

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.