calsfoundation@cals.org

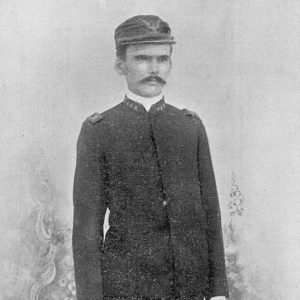

William Henry Abington (1870–1951)

William Henry (W. H.) Abington, a physician and a Democratic politician, served as a state senator and a state representative in the Arkansas General Assembly from 1923 to 1951. From 1929 to 1931, he was speaker of the Arkansas House of Representatives. As a legislator, he supported medically oriented legislation and established the Junior Agricultural School of Central Arkansas (now Arkansas State University–Beebe) in 1927.

W. H. Abington was born on January 2, 1870, in Collierville, Tennessee, to the farming family of William T. Abington and Mary Jane Plant Abington. He had an older sister and a younger brother. His family moved to White River (Prairie County) in 1870 but had relocated to Union (White County) by 1880. His brother, Eugene H. Abington, also became a physician.

Educated in the local schools, he graduated from South Kentucky College in Hopkinsville in 1889. Trained at the Arkansas Industrial University’s Medical Department—now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS)—he was licensed to practice medicine in 1892.

In 1896, he married Minnie Mae Herndon, who was from Judsonia (White County). The couple had no surviving children. In 1902, after his first wife’s death, he married Sarah Ann Sands, who was from Bald Knob (White County). The couple had three children.

Entering politics during the 1890s, he served as the mayor of Russell (White County) and later Bald Knob. During the gubernatorial campaigns of James P. Clarke and Jeff Davis, he managed their campaigns in White County.

Sometime in the early 1900s, former governor Clarke introduced him to William C. Faucette, who served as the mayor of Argenta, which is now North Little Rock (Pulaski County), from 1904 to 1909. After moving to Argenta about 1903, Abington served as an alderman during William Faucette’s tenure as mayor and began educating future physicians. From 1906 to 1909, he taught obstetrics and physiology at Little Rock’s College of Physicians and Surgeons medical school.

In 1909, he became a co-owner of the Beebe Drug Company and moved to Beebe (White County). In 1910, he was elected mayor of Beebe. After being reelected Beebe’s mayor in 1912, he resigned soon after taking office, saying that he needed to focus on his medical career.

Becoming a surgeon in the Arkansas National Guard, he served during the Mexican Border Incident in 1916 and in the First Arkansas Infantry during World War I.

After the war, he returned to Beebe. Elected a state senator in 1923, he supported strong medical licensing requirements and opposed the Arkansas Medical School’s mandatory two years of college-level pre-medical training for entering students. The requirement, he argued, prohibitively increased the expense and the time required to obtain medical degrees and contributed to a physician shortage in rural Arkansas. He charged that Morgan Smith, who was the dean of the medical school, and his “doctor trust” conspired to restrict the state’s supply of physicians.

In 1923, Abington introduced legislation designed to replace the medical school’s trustees with a five-member board of physicians empowered to remove Smith and lower the school’s admission requirement, but it died in the Senate.

After 1923, he repeatedly failed to secure passage of legislation intended to remove the medical school’s college requirement and allow the admission of high school graduates. In 1933, his frustration turned violent in the Senate chamber. In that year, the Senate public health committee rejected his bill aimed at lowering the medical school’s entrance requirement. In response, he physically attacked L. V. Parmley, a Little Rock (Pulaski County) surgeon and chair of the Arkansas Medical Society’s legislative committee, who had met with the Senate health committee. Both men were uninjured in the attack, and Abington later apologized to Parmley.

In 1925, despite his crusade against the medical school’s admission requirement, Abington successfully sponsored legislation that, combined with a separate bill authorizing the construction of a new medical school building, sought to build a state charity hospital. By 1927, insufficient funding canceled the planned construction of the hospital and the school building.

Abington continued to support the establishment of a state charity hospital. In 1938, the medical school still suffered from a lack of sufficient teaching hospital facilities and other problems, prompting the American Medical Association’s Education Council to withdraw its approval of the school. Governor Carl E. Bailey began efforts to restore the medical school’s rating, spurring the state legislature into action. In 1939, Abington voted for appropriations to support the medical school and a charity teaching hospital.

Despite Abington’s differences with Governor Bailey, who represented the reform faction within the state Democratic Party, the two men shared an interest in the well-being of senior citizens. In 1939, Bailey appointed him to serve as a commissioner in the State Department of Public Welfare. Abington, who disliked federal authority, chafed under the administration of State Welfare Director Gussie Haynie.

In 1939, Abington successfully sponsored legislation designed to decentralize the administration of the state welfare department, fund a hospitalization program for the indigent, and allocate a greater percentage of funding for old-age and blind pensions. Shortly after the bill’s passage, the Social Security Board withheld federal funding from the state. Abington blamed this action on “fake propaganda transmitted to the Social Security Board” and called for the act’s repeal. On March 10, 1939, Governor Bailey signed legislation to repeal the act and restore the State Welfare Department’s previous operating plan. Abington did not argue when Bailey decided not to reappoint him to the welfare department.

In 1943, Abington’s antistrike bill, which made it a felony to use force or threats of force to obstruct anyone from participating in their chosen vocation, was enacted into law.

In 1951, Abington introduced legislation designed to make the theft of hunting dogs a felony. In a much publicized action, state senators used the bark of a dog instead of “aye” to vote for the bill. Following Abington’s death on March 19, 1951, Governor Sidney S. McMath signed the dog bill into law. Abington is buried in Beebe Cemetery.

For additional information:

“Abington Deserts His Own Measure.” Hope Star, March 10, 1939, p. 1.

“Abington ‘Dog Bill’ Signed by Governor.” Northwest Arkansas Times, March 22, 1951, p. 1.

Abington, E. H. Back Roads and Bicarbonate: The Autobiography of an Arkansas Country Doctor. New York: Vintage Press, 1955.

Abington, W. H. “Who’s To Blame for Adverse Medical Legislation?” Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society 22 (December 1925): 153–159.

Baird, W. David. Medical Education in Arkansas, 1879–1978. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1978.

“Dr. Abington to Leave.” Arkansas Democrat, June 29, 1909, p. 10.

“Dr. W. H. Abington, Veteran Senator from Beebe, Dies.” Arkansas Gazette, March 23, 1951, p. 2.

Fletcher, John L. “Doc Abington—He’s an Unhappy Warrior.” Arkansas Gazette, January 14, 1951, p. 5F.

Johnson, Ben F., III. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Johnson, Lincoln, and Elizabeth Short. In and Around the Big Rock: A History of Bald Knob, Arkansas. Columbus, GA: Quill Publications, 1988.

Neil, Jerry. “Senators Yip Aye to Abington’s Bill.” Arkansas Gazette, February 21, 1951, p. 1.

“State Returned to Old Plan of Welfare Set-Up.” Arkansas Gazette, March 11, 1939, p. 1.

“Surgeon Attacked by State Senator.” Arkansas Gazette, February 9, 1933, p. 1.

Melanie K. Welch

Mayflower, Arkansas

Abington, William Henry

Abington, William Henry Arkansas State University–Beebe (ASU–Beebe)

Arkansas State University–Beebe (ASU–Beebe) Beebe (White County)

Beebe (White County) Des Arc (Prairie County)

Des Arc (Prairie County) Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Education, Higher

Education, Higher Health and Medicine

Health and Medicine North Little Rock (Pulaski County)

North Little Rock (Pulaski County) Orto, Zaphney

Orto, Zaphney Politics and Government

Politics and Government Russell (White County)

Russell (White County) Spanish-American War

Spanish-American War Strawberry Industry

Strawberry Industry University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS)

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Eugene Abington

Eugene Abington

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.