calsfoundation@cals.org

Act 258 of 1909

aka: Toney Bill to Prevent Lynching

Act 258 of 1909 was a law intended to prevent citizens from engaging in lynching. It was not, strictly speaking, a piece of anti-lynching legislation, as it imposed no punishment for the crime of lynching. Instead, it aimed to expedite trials relating to particular crimes in order to render what would likely be a death penalty verdict to mollify the local population enough that they would not take the law into their own hands. Such a law as Act 258 is indicative of the connection between lynching and the modern death penalty observed by some scholars; as Michael J. Pfeifer noted in his 2011 book, The Roots of Rough Justice: Origins of American Lynching, legislators across the nation “reshaped the death penalty in the early twentieth century to make capital punishment more efficient and more racial, achieving a compromise between the observations of legal forms long emphasized by due process advocates and the lethal, ritualized retribution long sought by rough justice supporters.”

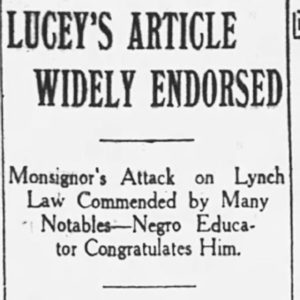

Act 258 was written by Father John Michael Lucey, a Catholic priest and founder of the Colored Industrial Institute in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). As he wrote it, the law mandated that when there was committed a “rape, murder, or any other crime, calculated to arouse the passions of the people” to such an extent that mob violence was likely, then the sheriff “shall notify the judge of the circuit or district” and request “a special term of the court in order that the person or persons charged with such a crime or crimes may be brought to immediate trial.” Lucey, however, did not apparently intend the expedited trial to be a means of swiftly determining the guilt or innocence of the accused; as he was wrote to the Arkansas Gazette, he wanted “to bring about a speedy trial of the brute who outrages the laws of God and man and thereby so inflames the mind of a community that a quick disposition of his case is the only way to restore peace and normal conditions.” Indeed, as Lucey acknowledged, part of his own motivation for producing the bill was to prevent the enactment of more severe anti-lynching legislation, such as that previously introduced into the Arkansas General Assembly by Senator Kie Oldham in 1907. Oldham’s bill would have permitted speedy trials should the danger of lynching arise but would also have fined, imprisoned, and/or removed from office local officials who allowed prisoners to be taken from their custody.

Father Lucey convinced state Senator Hardin K. Toney to introduce the bill, which became Senate Bill 88 (SB 88). It was referred to the Judiciary Committee on January 25, 1909, and Lucey testified on behalf of the measure. Many committee members reportedly looked unfavorably upon the bill, in part because nothing in the bill prevented defendants from requesting a change of venue due to prevailing local conditions. However, the bill passed the Senate on April 7, 1909, by a vote of 21–4 and moved on to the Arkansas House of Representatives, where it passed on May 12, 1909, by a vote of 54–24. Governor George Washington Donaghey signed the bill into law.

Arkansas jurists well understood that Act 258 was not intended to protect the rights of the accused but rather to facilitate an execution in order to stave off mob desire for immediate revenge. For example, following the lynching of Will Norman in Hot Springs (Garland County) in 1913, Circuit Judge Calvin T. Cotham referenced Act 258 of 1909 as a tool that would have facilitated a quick trial, adding, “It would have been a much better lesson had [Norman] been executed after a fair trial, not by self-appointed executioners who had neither legal nor moral right to take away his life.” In perhaps the most notable example of the “success” of the legislation, Act 258 was invoked following the Catcher Race Riot of 1923, allowing for the expedited trial and execution of Son Bettis and Charles Spurgeon Rucks. The alleged rape and murder of which they were accused occurred on December 28, 1923; their trial, including sentencing, was held January 4–5, 1924.

Later developments in national and state jurisprudence mean that Act 258 no longer remains in effect, although racial disparities in the use of the death penalty continue to exist, with one factor being a poorly funded public defender system that leaves public defense attorneys with little time to prepare for trials.

For additional information:

Acts of Arkansas of the General Assembly of the State of Arkansas, 1909. Little Rock: General Assembly of the State of Arkansas, 1909.

“Among the Law Makers.” Arkansas Democrat, February 11, 1909, p. 3.

Lancaster, Guy. American Atrocity: The Types of Violence in Lynching. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2021.

“News and Notes of the Legislature.” Arkansas Gazette, February 11, 1909, p. 3.

“Suppression of Mob Violence.” Arkansas Gazette, January 27, 1907, p. 16.

“To Prevent Lynchings.” Arkansas Gazette, February 16, 1909, p. 5.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Law

Law J. M. Lucey Anti-Lynching Article

J. M. Lucey Anti-Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.