calsfoundation@cals.org

Gillam Park

Gillam Park was purchased by the city of Little Rock (Pulaski County) in the 1930s as a place to relocate jobless and homeless citizens during the Great Depression. It later became the site of a segregated Jim Crow–era park. Subsequently, it was the cornerstone of a multi-million-dollar slum clearance and urban redevelopment plan that sought to relocate much of the African-American population into that part of the city. In the twenty-first century, it is managed by Audubon Arkansas as a site of natural significance. The park is named in honor of Isaac Taylor Gillam.

The purchase of Gillam Park was authorized by Mayor Horace A. Knowlton and the Little Rock City Council at a meeting on November 22, 1934, with the approval and support of the Little Rock Chamber of Commerce. The purchase addressed two problems. The first was the growing homeless population in the city, which was being fed and sheltered during the Great Depression era by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). The second was the lack of recreational facilities for Little Rock’s black population. Although the city funded six whites-only parks, it provided none for its black population, contravening the established segregation principle to provide “separate but equal” facilities.

At the end of 1935, the city council proposed a bond issue of $15,000 “to purchase, improve and to cover the city’s contribution for the development of the colored park.” The park bond issue was bundled with two other bond issues, one for $468,000 to build the then-segregated downtown Robinson Auditorium, and another for $25,000 to construct and equip a segregated addition to the city library. The bond issue for the black park was added “as sop” to win black support for the white projects and to encourage white voters to support the black park project. All three bonds passed in January 1937.

However, it was not until after World War II that the city turned its attention back to Gillam Park, responding to protests from the black community. The city agreed to issue a bond for $359,000 to pay for the development of black recreational facilities at Gillam Park. In doing so, the city fully expected the bond issue to fail, but at least, it believed, it would show token goodwill. The bond issue went to the voters on February 1, 1949. Then, as the Arkansas State Press, a black newspaper owned by L. C. and Daisy Bates, described it, “The unexpected happened—the bond issue passed and has made the city the acme of deception and the laughing stock of the entire south.” The Arkansas State Press predicted, “It is not going to be spent any time in the near future if there is any way for the present administration to stop it.”

Nothing did happen until the following year, when the city used the bond money as a lure for newly available federal money to initiate a comprehensive program of urban renewal that would involve the purposeful and premeditated development of segregated neighborhoods in the city. A special election held in January 1950 mandated the city’s slum clearance and urban redevelopment plans, and the black park bond issue was successfully used to secure a federal grant of $9,641,000.

With the urban renewal money, work at Gillam Park quickly began. By August 1950, there had been an opening ceremony for the newly built swimming pool. Less than a year after opening, however, the Gillam Park swimming pool was reported leaking. Attendance was poor. Problems came to a head in July 1954 when Tommy Grigsby, a black boy, drowned in the Gillam Park pool. At the time, the pool was understaffed with lifeguards, and it lacked a respirator that might have saved Grigsby’s life. Its remote location also meant that a doctor and rescue squad could not reach the scene in time to resuscitate him.

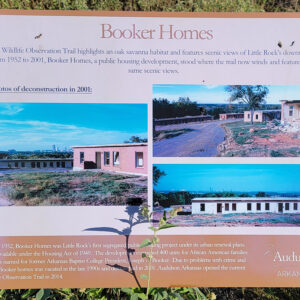

The city’s first segregated public housing projects under its urban renewal plans were the 400 units of Joseph A. Booker Homes built adjacent to Gillam Park at Granite Mountain. In 1952, Booker High School was built next to Booker Homes. Due to racial gerrymandering, it emerged that although Gillam Park, Booker Homes, and Booker High School all fell within the city limits and could qualify for federal funds for slum clearance and urban redevelopment, the Little Rock School District parameters ended just short of the school. As a result, the area fell instead within the Pulaski County Special (Rural) School District.

Booker High School opened in September 1952 under crowded conditions. There was not even enough room to accommodate all of the children of the black families residing at Booker Homes, so more than 100 black students were left without provisions for their education. Such was the outrage among black and some white sections of the population in Little Rock that the Arkansas General Assembly was forced to rush through the “Booker Bill,” which required Booker High School to be incorporated into the Little Rock School District.

In the 1990s, the Booker Homes development was demolished due to problems with crime and drugs. Mining and other industries have operated at Granite Mountain near Gillam Park, and it is on the regular flight path for the Bill and Hillary Clinton National Airport, prompting allegations of environmental racism.

In the twenty-first century, Gillam Park is managed by Audubon Arkansas, which has its Little Rock Audubon Center nearby. The park contains one of the few exposed igneous rock clusters of nepheline syenite in the world, with an endangered and federally protected plant, the small-headed pipewort, growing on top of the cluster. One of the state’s oldest groups of whiteoak trees also stands on the land.

For additional information:

Kirk, John A. “Housing, Urban Development and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the Post-Civil Rights South.” Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Society and Culture. Special Issue: “The Black South since the Civil Rights Movement.” 8 (Winter 2006): 47–60.

———. “Plan for the Homeless Echoes Gillam Park’s History.” Arkansas Times, July 20, 2017, pp. 12–13. Online at https://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/plan-for-the-homeless-echoes-gillam-park-history/Content?oid=8133527 (accessed November 14, 2017).

———. “‘A Study in Second-Class Citizenship’: Race, Urban Development and Little Rock’s Gillam Park, 1934–2004.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 64 (Autumn 2005): 262–286.

John A. Kirk

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Audubon Trail

Audubon Trail  Booker Homes Sign

Booker Homes Sign  Gillam Park Neighborhood

Gillam Park Neighborhood  Gillam Park View

Gillam Park View

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.