calsfoundation@cals.org

Hardy (Sharp County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 36°18’57” N 091°28’57″W |

| Elevation: | 358 feet |

| Area: | 5.06 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 743 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | July 12, 1894 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

347 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

329 |

399 |

508 |

721 |

599 |

555 |

692 |

643 |

538 |

578 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

772 |

743 |

|

Located in northern Arkansas on the Spring River, Hardy (Sharp County) was established in 1883 as a result of the construction of the Kansas City, Springfield, and Memphis Railroad. The town emerged in the twentieth century as a popular tourist destination for Mid-southerners seeking the natural beauty of the Ozark foothills.

The Arkansas General Assembly’s 1867 decision to pay companies $10,000 for every mile of track laid led to a statewide boom in railway construction. The Kansas City, Springfield, and Memphis Railroad through Arkansas was built, at least in part, because of this incentive.

Named for railroad contractor James A. Hardy of Batesville (Independence County), the town was developed on 600 acres of land by early settler Walker Clayton in 1883 to service the needs of travelers. Clayton also donated the land for what is now called the Hardy Cemetery Historic Section. Residents wanted to name the town Forty Islands after a nearby creek, but the U.S. Post Office insisted on Hardy because that designation was used to deliver mail to railroad workers in the area. This was not the last time an outsider influenced the direction of Hardy’s development.

When Hardy was incorporated, it was far removed from the county seat in Evening Shade. Feeling isolated from their government, Hardy residents complained to the General Assembly for a solution to the problems of distance and poor roads. In 1894, the state divided Sharp County into two sections, with Hardy named county seat of the Northern District. A court was established along with other government offices, which increased Hardy’s population to 347 people by 1900. As the twentieth century progressed, better roads made the dual-county-seat structure unnecessary, so Ash Flat was designated the county seat in 1963.

In 1908, Memphis physician George Gillespie Buford and his wife were temporarily stranded in Hardy when their train experienced a mechanical failure. The couple climbed Wahpeton Hill on the south bank of the Spring River and was charmed by the area’s natural beauty. The following year, the Bufords purchased fifty acres on Wahpeton, where they built a summer cottage.

Over the next few years, Buford expanded his land holdings by purchasing the nearby Jordan and East Wahpeton hills. In 1912, the Memphis physician constructed ten cottages for summer visitors on his newly acquired property, which he named Wahpeton Inn. Blytheville (Mississippi County) native L. L. Ward opened a second resort, Rio Vista, in 1932. In addition to the resorts, several Memphis youth organizations established summer camps near Hardy. The Girl Scouts established Camp Kiwani in 1920; Miramichee was built by the YWCA in 1916, and the Boy Scouts constructed Kia Kima in 1916. In addition to the railroad, bus service also connected Hardy to the rest of the world. By 1930, the town held 508 permanent residents, but its visitor population swelled to 1,000 per day between July and September.

The tourism boom spawned by Wahpeton, Rio Vista, and the summer camps in turn led to economic growth. By 1920, two blocks of Main Street were filled with several businesses, including a bank, two cafés, two drug stores, a Ford automobile dealership, and a grocery. Town leaders—perhaps most notably drugstore-owner William Johnston—tirelessly promoted Hardy as a place where city dwellers could find relaxation. In an interview with a Memphis Press-Scimitar reporter, Johnston boasted that Hardy had the “finest fishing in the world….” Although most residents welcomed tourists, some townspeople found it difficult to adjust as the average population increased by thousands during the summer months. In 1935, café owner Tennie Meeker exclaimed: “You take a big trainload of people and dump them down suddenly in a small town like Hardy, and it nearly works everybody to death.”

Hardy Alton “Spider” Rowland, born near Hardy, was a nationally known newspaperman in the 1940s. The Wilburn Brothers, also from Hardy, were popular country music singers in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

As the twentieth century progressed, tourists increasingly relied on automobiles to travel to the Spring River area. Resting near the intersection of national highways 62 and 63, Hardy was easily accessible for those who traveled by car. When large-scale federal highway construction began in the 1950s, the tourism population shifted from long-term visitors to those looking for a weekend getaway. Recognizing this trend, the Wahpeton resort individually sold its cottages in 1953. The established tourism industry in Hardy was augmented in 1955 with the construction of retirement homes by West Memphis (Crittenden County) developer John Cooper. The founding of Cherokee Village (Sharp County) increased tourism to the Ozark foothills, and within a decade, the Hardy area was recognized as an important retirement center. In 1968, the Arkansaw Traveller Folk Theater was established in Hardy to preserve the culture of the Ozarks. When the railroad depot closed in the 1970s, some Main Street businesses relocated. This relocation accelerated when the Spring River flooded in December 1982. In their place, shops specializing in antiques and crafts were opened, which, along with the draw of the Ozarks’ natural beauty, has helped Hardy remain a popular tourist destination. In 2014, the Discovery Channel broadcast a six-episode “reality television” series called Clash of the Ozarks, set in Hardy.

For additional information:

Moore, Caruth Shaver. Early History of Evening Shade and Sharp County. Evening Shade, AR: 1979

The Timely Club. The Hardy History. Batesville, AR: Riverside Graphics, 1980.

G. Wayne Dowdy

Memphis Public Library and Information Center

Arkansas Traveler Theater

Arkansas Traveler Theater  "Frisco" Railway near Hardy

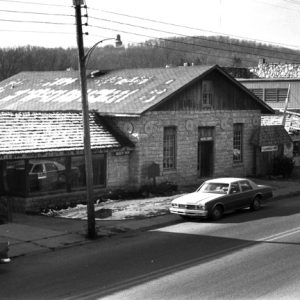

"Frisco" Railway near Hardy  Hardy Amoco Station

Hardy Amoco Station  Hardy Cemetery Historic Section

Hardy Cemetery Historic Section  Hardy Historic Mural

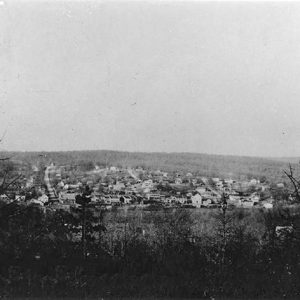

Hardy Historic Mural  Hardy Overlook

Hardy Overlook  Hardy Sign

Hardy Sign  Hardy Street Scene

Hardy Street Scene  Hardy Street Scene

Hardy Street Scene  Hardy Street Scene

Hardy Street Scene  Hardy, View From River

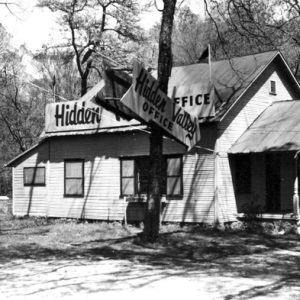

Hardy, View From River  Hidden Valley Office

Hidden Valley Office  Sharp County Courthouse

Sharp County Courthouse  Sharp County Courthouse

Sharp County Courthouse  Sharp County Map

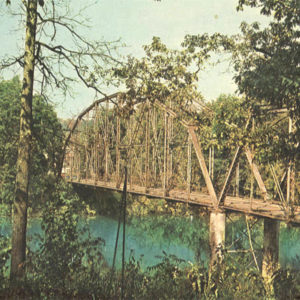

Sharp County Map  Spring River Bridge

Spring River Bridge  Thunderbird Lodge

Thunderbird Lodge

I was a Boy Scout living in Memphis, Tennessee. In 1953, my parents, desiring to go on a vacation by themselves, volunteered me to the confines of Camp Kia Kima for eight weeks. The camp was overflowing, and the cabins were all filled. I was among a number of scouts assigned to live, for the duration, in smelly canvas tents on a hillside near the main camp. The camp had a shortage of counselors, and a few sadistic young men were assigned to ride herd on us. We were trained like Marines at Paris Island, and any form of escape was clearly discouraged. We were trapped on the wrong side of the river, and any boats were securely locked up. Only guile and a pretense at religion enabled a number of us to attend church services in Hardy. I was too short on cash to purchase a train ticket. After convincing one of the counselor overlords that I wished to contribute to the church collection, I was loaned an extra quarter. If I failed to pay back the debt, I would become his gofer and lackey for my three remaining weeks. While all heads were bowed in humble submission, I silently slipped out of my pew and sneaked out the door. I made a quick dash to the train station and bought a ticket to Memphis. Careful planning ensured that the awaiting train was there. My greatest recollection is that of a red-faced counselor running along the station platform as I waved goodbye from the rear car. I can proudly say that I am probably the only thirteen year old who escaped intact from the confines of Camp Kia Kima. My vacation at home, without my parents, for the next four days was most enjoyable. I won’t describe the events that followed. I am truly grateful that Hardy was placed along the railroad. All scout camps should be placed near train tracks.