calsfoundation@cals.org

Alexis Karl Hartman (1838–1899)

Alexis Karl Hartman was the first elected Reconstruction mayor of Little Rock (Pulaski County), winning the office in January 1869 for an eleven-month term and again in November 1869 for a two-year term. Reflecting the contentious politics of the Reconstruction years, he is the only Little Rock mayor who was twice suspended from office by the city council. In 1871, he lost his bid for a third term.

Alexis Hartman was born on August 22, 1838, in Saxony, a province of Prussia, and studied medicine there. In the late 1850s, he immigrated to the United States, and on June 7, 1859, he married Margaret Althus in St. Clair County, Illinois. The couple settled in O’Fallon, a town near St. Louis, Missouri, and were living there in 1864 when he joined the Forty-Third Regiment of the Illinois Infantry as an “assistant surgeon.” He served on the regimental staff in Little Rock from September 1, 1864, until December 31, 1864, when he resigned “for the good of the service.” After the Civil War ended, Hartman returned to Little Rock with his wife and three children. The couple had one more child while living in the city.

In Little Rock, Hartman practiced medicine, spending much of his time providing care to the freedmen who had flocked to Little Rock during and immediately after the war. He was appointed city physician in 1868 to treat indigent patients. He continued to hold that position throughout 1869, even as he served as mayor. His work as a physician made him highly appreciated by the city’s African Americans, as expressed in a long poem published in the Morning Republican containing this verse: “The widow, the orphan, the sick and the poor, / His help never would ask in vain. / Hope and relief at misery’s door / He’d leave, over and over again.”

Hartman’s popularity with black voters, who in 1869 were newly enfranchised and made up a majority of registered Little Rock voters, was instrumental in his election as mayor by lopsided margins. As the Republican nominee, he was elected to the office in January 1869 by a vote of 1,106 to 310 and in November 1869 by a vote of 813 to 159.

During his first term, from January to November 1869, Hartman dominated the city council so thoroughly that the Daily Arkansas Gazette described him as a boss and nicknamed him “Count Bismarck.” The paper, whose writers often expressed deep enmity toward Hartman and his Radical Republican views, described him as “large and corpulent, resembling much a large lager beer barrel, of which he is said to be very fond.” It reported that Hartman had a “dull sneaking look in his eye, and is in no manner prepossessing in appearance.” Many years later, however, former Little Rock mayor Frederick Kramer recalled him as being a “fine looking man.”

Democratic-Conservative Party leaders and the Gazette accused Hartman of corruption during his first term, mainly because the expenditures of the rapidly growing city rose substantially during that time and the city had inadequate tax revenues to pay its bills. To make up the difference, the city borrowed funds using its own scrip and other debt instruments. Despite the opportunity for abuse of borrowing powers, an independent audit of city finances in December 1869 found no evidence of the misuse of city funds, and no evidence of criminality in city finances during Hartman’s administration was ever documented.

Hartman’s domination of the council ended when his first term expired. A month before the November election, Hartman had joined the reform Republicans, an emerging faction of the Republican Party opposed to the leadership of Governor Powell Clayton. This affiliation did not endear him to the six aldermen who were aligned—some closely, some loosely—with the regular Republicans loyal to Clayton.

Hartman damaged his relationship with council members not long after the November 1869 election by sending them a letter demanding that they remove from office two newly elected aldermen whom he maintained were not qualified under law to hold office. One of his targets was Frederick Kramer. In the letter, dated November 13, 1869, Hartman wrote: “I have undeniable information that Mr. Frederick Kramer, one of the aldermen elect of the 1st ward, has voted ‘against’ the present constitution of the state of Arkansas, and consequently could not register, and in fact has not registered under the state legislation. He has also by taking the oath of office required by law committed perjury.” This letter outraged most of the council members, who tossed it aside and denounced Hartman for writing it. Three months later, still angry with him and unimpressed with his performance as mayor, the city council by a 5–3 vote declared the office of mayor vacant and stopped paying the mayor’s salary. Most of the council’s actions against Hartman were overturned by a court decision, but by then the council had transferred the bulk of the mayor’s powers to the president of the city council.

During the 1870 election, Hartman got into deeper trouble with the city council when he joined other reform Republicans (who had acquired the name “brindletails”) in a plot to “usurp” (meaning, take possession of) Pulaski County’s polling places. Hartman led the usurpation of Little Rock’s First Ward. As planned, a group of brindletails occupied the polling place (the truck house of the Defiance Hook and Ladder Company) early in the morning and tried to keep the regular election judges from entering it. However, an officer of the volunteer fire company used his key to open the building; he then ordered the occupiers out and invited the regular judges in.

The regular judges opened the Ward 1 polling place on time, but the brindletails assembled outside on the building’s porch and pretended they did not see the regular judges and open poll. They elected their own election judges and opened an outside poll. Hartman spent the day directing African-American voters to the outside poll, telling them that the one inside was illegal. The candidates supported by the brindletails won by huge margins at the outside polls but lost equally badly at the regular polls. Ultimately, the victors at the regular polls—who were backed by the regular Republicans, known as the “minstrels”—were seated on the Little Rock city council.

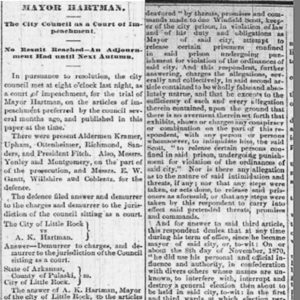

Hartman’s interference with the election had repercussions. On December 1, 1870, “misdemeanor in office” charges were brought against him, and an impeachment trial was scheduled. When a court order delayed the trial, the council suspended Hartman from office on December 31, 1870, until he was found innocent of the charges.

On March 2, 1871, Hartman suddenly renounced the brindletails, claiming they had tricked him into “doing dirty work” for them. Further, he wrote in a letter: “Messr. Brooks [meaning Joseph Brooks, of the subsequent 1874 Brooks-Baxter War], Hodges, & Co. have shown themselves to be entirely unfit to be the leaders of the Republican party—wanting in honesty and patriotism…I consider it my duty as a Republican to support Governor Clayton and his administration.” Hartman’s repudiation of the brindletails likely saved him from being removed from office when, on May 5, 1871, the council finally convened his trial and quickly adjourned the proceedings until late October, just a few days before the expiration of Hartman’s term of office and the 1871 election.

Apparently willing to overlook the fact that Hartman had assisted a plot to steal the 1870 election from them, the minstrels nominated Hartman—the man whom minstrel council members had twice removed from office—as their candidate for mayor on October 9, 1871. On October 30, barely a week before the election, the city council reconvened Hartman’s impeachment trial and voted 4–1 to acquit him of the charges. By another 4–1 vote, the council expunged the charges against Hartman from the record.

Hartman lost the election to General Robert F. Catterson, the brindletail candidate who, as a U.S. marshal, had been one of his co-conspirators in the 1870 usurpation plot. The vote was 710 to 374.

Hartman and his family left Little Rock in August 1872, and he attended the St. Louis School of Medicine, which later became the Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM). He graduated in 1878 and became a respected physician in St. Louis as did his son, a grandson, and a great-grandson. He never again ran for office. Hartman died on January 10, 1899. He is buried at the Old Saint Marcus Cemetery in St. Louis.

For additional information:

“The Charges against the Mayor.” Daily Arkansas Gazette, December 3, 1870, p. 4.

“City Council Grossly Insulted by Mayor.” Morning Republican, November 19, 1869, p. 4.

“Dr. Hartman Dead.” St. Louis Republic, January 12, 1899, p. 12.

Durning, Dan. “Mayor A. K. Hartman and the Brindletails Usurp Little Rock’s 1870 Election, to No Avail.” Pulaski County Historical Review 66 (Winter 2018): 122–140.

Report No. 512, An Inquiry into Certain Charges Against Hon. Powell Clayton in Reports of the Committees of the Senate of the United States for the Third Session of the Forty-Second Congress, 1872–73. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1872. Online at https://books.google.com/books?id=t8RYAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed February 1, 2018).

“To A. K. Hartman.” Morning Republican, January 8, 1869, p. 2.

Dan Durning

Birch Bay, Washington

Law

Law Politics and Government

Politics and Government Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Hartman Impeachment Article

Hartman Impeachment Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.