calsfoundation@cals.org

Lewis Nathan Rhoton (1868–1936)

Lewis Nathan Rhoton was a Little Rock lawyer who, as Sixth District prosecuting attorney (covering Pulaski and Perry counties) from 1904 to 1908, exposed the Boodle Scandal in the spring 1905 session of the Arkansas General Assembly (“boodle” is a slang term meaning bribe money). His actions in fighting corruption played an important role in the rise of Progressivism in the state. President Theodore Roosevelt, while visiting Little Rock (Pulaski County) on October 25, 1905, congratulated him for “invaluable service to the state and nation” in calling corrupt public officials to account.

Lewis Rhoton was born on May 13, 1868, to Franklin Rhoton and Susannah Garrett Rhoton, in Henry County, Indiana. An outstanding student, Rhoton received his higher education from the Illinois State Normal School (a teachers’ college). There, he met Jacob R. Rightsell, Little Rock school superintendent, who hired him as principal of the Scott Street School. Later, he headed the Peabody School, the city’s high school. Attending night classes, Rhoton graduated in 1894 from the Little Rock law department of the University of Arkansas (UA). He did postgraduate study at the University of Virginia and, upon returning to Little Rock in 1896, married Elizabeth (Bessie) Riffle. The couple built a home at 2222 Marshall Street and had two children, a son, Riffle Garrett Rhoton, and a daughter, Bayard Frances Rhoton. Rhoton established a general law practice, taught law classes, and served as a deputy prosecuting attorney from 1901 until his election as prosecutor in 1904.

Prosecuting Attorney Rhoton immediately began investigating suspected boodling by Arkansas legislators. Since 1895, a well-known lobbyist, Tom Cox, was rumored to have been paying off legislators on behalf of various corporate interests. Rhoton sought advice from Missouri governor Joseph W. Folk, famous for earlier boodler prosecutions in St. Louis. As a result, the prosecutor hired undercover detectives from that city to seek evidence during the spring 1905 Arkansas legislative session.

After the 1905 Arkansas General Assembly adjourned, Rhoton led grand juries to issue subpoenas and indictments over the next three years. In the end, sixteen state senators and representatives, one mayor, and three other individuals were arraigned. He received wide acclaim in Arkansas for his campaign of what many called civic righteousness. Trials revealed that bribery of legislators was not confined to lobbying malfeasance for corporations but was instead a common practice of greedy legislators extorting money from ordinary citizens seeking legislation.

Without sufficient funding for his office, Rhoton had to take on additional cases to earn money for boodle investigations by winning fines from corporations violating Arkansas’s antitrust law. He would eventually appear before the U.S. Supreme Court in early 1908 to argue successfully for this law in Hammond Packing Company v. Arkansas. Long delays hampered his prosecution of the boodle cases as defense attorneys secured continuances of cases. Jury tampering also occurred. In the end, Rhoton was able to bring to trial only nine cases involving seven defendants. He obtained convictions in four cases against five defendants, with two mistrials, two acquittals, and one case reversed on appeal. Arkansas’s laws did not provide strong penalties for bribery. Only one member of the Arkansas General Assembly was sent to prison, and he was pardoned after six months. Some crooked officials were saved by a three-year statute of limitations. Rhoton’s zealous efforts virtually destroyed his health.

Rhoton’s pursuit of boodlers was an important influence on the growth of Progressivism in Arkansas from 1907 to 1910. The Arkansas Gazette credited the prosecutor for the remarkably reformist and “honest legislature” of 1907: “[T]his sudden turn of legislative action from the interests of corporations to the interests of the people was accomplished by the heroic work done by Lewis Rhoton, at great personal expense to himself, to drive from the legislative halls corruption and bribery existing there for many years and to place the people again in power in the legislative department of our state.”

In winning nomination for an unprecedented third term as prosecutor in 1908, Rhoton had to battle U.S. senator Jeff Davis, who vowed to have him defeated. Previously, the prosecutor had the senator subpoenaed before a grand jury investigating use of illegal “free passes,” which were issued for travel without charge by railroads to favored politicians and officeholders. His clashes with Davis, in one instance a face-to-face confrontation at a campaign event, and his revelations of pervasive political corruption helped elect businessman George W. Donaghey, the state’s first real Progressive governor.

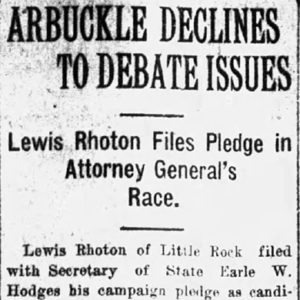

Rhoton’s success in exposing the boodlers of 1905, however, did not end political corruption in Arkansas. Rumors and investigations of legislative misdeeds continued after he left office due to ill health in 1908. After he unsuccessfully ran for state attorney general in 1916, he temporarily returned to public service to assist a new prosecuting attorney secure bribery convictions of two state senators in 1917.

In private practice of law for much of his life, Rhoton often served as a defense attorney. He cooperated on several cases throughout his career with Little Rock’s most prominent African-American attorney, Scipio A. Jones, an association for which Senator Davis had attacked him politically in 1908. Rhoton and Jones worked on ordinary criminal cases, as well as more significant ones, including a 1918 case claiming jury discrimination by an all-white jury. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) engaged him, together with Jones and other white attorneys, in 1935 to handle appeals of black youths in the Arkansas “Scottsboro” Case.

Lewis Rhoton died on July 14, 1936, and is buried at Roselawn Memorial Park in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Willis, James F. “Lewis Rhoton and the ‘Boodlers:’ Political Corruption and Reform During Arkansas’s Progressive Era.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 76 (Summer 2017): 95–124.

“Lewis Rhoton Ex-Prosecutor Succumbs.” Arkansas Gazette, July 15, 1936, p. 10.

Willis, James F. “Antitrust in Arkansas Politics during the Progressive Era.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Winter 2021): 436–467.

James F. Willis

Little Rock, Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Hammond Packing Company v. Arkansas

Hammond Packing Company v. Arkansas Law

Law Politics and Government

Politics and Government Peabody School

Peabody School  Lewis Rhoton Article

Lewis Rhoton Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.