calsfoundation@cals.org

David Augustine Elihue Johnston (1878?–1919)

David Augustine Elihue Johnston, also known as D. A. E. Johnston or Elihue Johnston, was an inventor, a successful dentist and businessman, and a member of the National Negro Business Men’s League. He and his brothers were killed under mysterious circumstances during the time of the Elaine Massacre of 1919.

D. A. E. Johnston was born in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), although sources differ as to the year. Johnston’s official date of birth is listed as May 1, 1878, on his application for a draft exemption with the Phillips County Local Exemption Board on September 12, 1918. On the 1900 U.S. Census, he was listed as being born in May 1881, but on his January 1910 marriage license, his age was listed as twenty-five, which would make him born around 1884. Johnston was the son of the Reverend Lewis Johnston Jr. (1847–1903), who was a native of Pennsylvania, and Mercy Ann Taborn Johnston (1848–1927), a native of North Carolina. He had six siblings. His father was the first ordained black minister of the Covenanter Church and served in the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War. His mother was a teacher and later became an undertaker in Muskogee, Oklahoma. His parents also founded the Richard Allen Institute, one of the earliest Presbyterian schools for African Americans in Arkansas, in Pine Bluff in 1886.

Johnston attended classes at the Richard Allen Institute and then received his dental training at the Chicago School of Dentistry in Chicago, Illinois. He practiced dentistry in Chicago before moving back to Arkansas to practice dentistry in Pine Bluff. He then moved to Helena (Phillips County) to set up a practice with R. F. Johnson at 508 Ohio Street; they also established a branch office at Holly Grove (Monroe County).

In January 1910, he married Mariah (or Maria) Estelle Miller, daughter of the Reverend Abraham Hugo Miller and Eliza Ann Ross Miller. Johnston and his wife had three children.

In August 1910, Johnston, along with attorney Scipio A. Jones, were among the Arkansas delegates attending the National Negro Business Men’s League convention in New York. The delegates made a plea for the 1911 convention to be held in Little Rock (Pulaski County) by bringing with them personal invitations from Governor George Washington Donaghey, Mayor W. R. Duley, many prominent citizens, and the state’s Board of Trade. Their efforts at having the convention in Little Rock in 1911 were successful, and Johnston attended that year’s convention in Arkansas’s capital city.

In 1913, Johnston began working on an invention that would improve the typing experience—the typewriter attachment. He applied for Letters-Patent on January 1913 and received a patent on January 30, 1917, for his invention. He was offered $25,000 for the right to manufacture his typewriter attachment in Canada and $50,000 for the ownership of the typewriter attachment in Canada. It is unknown if Johnston sold his typewriter attachment or ever had it marketed.

In 1918, Johnston applied for, and was granted, an exemption by the Phillips County Local Exemption Board, so he did not serve in the military during World War I.

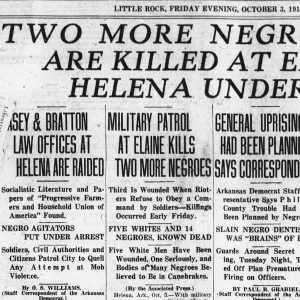

On October 2, 1919, while returning home from hunting with his brothers—Dr. L. H. Johnston, Gibson Allen Johnston, and Leroy Johnston—he was allegedly approached in Ratio (Phillips County) by a white man whom he considered a friend and warned to leave the vehicle because it was too dangerous to drive to Helena. This friend urged Johnston to catch the train to avoid the violence that had begun on September 30, now known as the Elaine Massacre, after a shooting incident at a meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America escalated into mob violence instigated by white people in Elaine and surrounding areas. After getting on the train, Johnston and his three brothers were arrested when the train reached Elaine (Phillips County) on the charges of “distributing ammunition to the insurrectionists” and chained together by Alderman Orlie R. Lilly and other posse members (all of them white).

The official version of the next events that was released to the newspapers by Phillips County officials states that there were minor problems with the motor of Lilly’s vehicle, and while the other men were busy with the vehicle, Johnston allegedly grabbed Lilly’s gun from his pants pocket and shot Lilly three to four times in either his back or his lungs. The other posse members then fired, killing Johnston and his three brothers. The posse members then dumped the brothers’ bodies on the side of the road, still chained together or tied with rope. It was also claimed that Johnston was “the ringleader” of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union and the “brains of the plan.” It was also reported that several high-powered rifles and ammunition boxes were seized from Johnston’s office at 224 Walnut Street in Helena.

By contrast, the Crisis (the official publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) and Bessie Ferguson (author of the 1927 master’s thesis “The Elaine Race Riot”) reported that Lilly had argued with Johnston the week before the incident and that Lilly or a friend had tried to whip Johnston but was instead beaten in the fight. When Johnston realized that he was about to be turned over to a mob, he grabbed Lilly’s gun and shot him. The mob then shot the brothers. Another version of events offered by B. Boren McCool, a historian and author of Union, Reaction, and Riot: The Biography of a Rural Race Riot, holds that a prominent plantation owner had shot Lilly and then killed Johnston and his brothers to cover up the murder. Some black newspapers, including the Crisis and Tulsa World, also reported that the bodies of the Johnston brothers were held for ransom until their mother, Mercy Johnston, paid the money in order to bury her sons.

Some articles also claimed that Johnston had previous encounters with the law; this could be in reference to a 1902 incident in which Johnston was ticketed and fined three dollars for riding his bicycle without a light. Because he was also a druggist, some out-of-state articles claimed that he was a drug dealer.

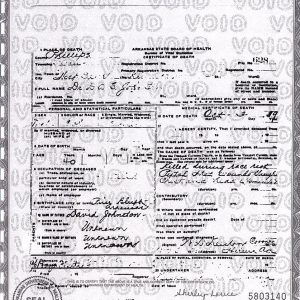

Although some books and black newspapers claim that the Johnston brothers were buried in Little Rock, according to the Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, the Arkansas Democrat, and the Arkansas Gazette, their bodies were brought back to their childhood hometown of Pine Bluff for their funerals and burial. Johnston’s official Arkansas death certificate on file with the State of Arkansas’s Vital Records, dated October 3, 1919, noted that he was “killed during race riot” and shot “through chest and head,” although there exists another version of the death certificate that mentions only “gunshot wounds.”

For additional information:

Butts, J. W., and Dorothy James. “The Underlying Causes of the Elaine Riot of 1919.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Spring 1961): 95–104.

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Dunaway, L. S. What A Preacher Saw Through a Keyhole in Arkansas. Little Rock: Parke-Harper Publishing Company, 1925.

Ferguson, Bessie. “The Elaine Race Riot.” Master’s thesis, George Peabody College for Teachers (now Peabody College of Education and Human Development at Vanderbilt University), 1927.

Hanna, H. L., ed. Bureau of Investigation Reports and Correspondence on the Phillips County War of 1919. N.p.: CreateSpace, 2017.

“Lived at Pine Bluff—Bodies of Four Johnston Brothers Taken There for Burial.” Arkansas Gazette, October 4, 1919, p. 3.

McCool, B. Boren. Union, Reaction, and Riot: The Biography of a Rural Race Riot. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1970.

“Negro Special to New York Tonight—Arkansas Delegates Will Seek National Negro Business Men’s League Convention for This City.” Arkansas Gazette, August 13, 1910, p. 9.

Rogers, O. A., Jr. “The Elaine Race Riots of 1919.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 19 (Summer 1960): 142–150.

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

“Wealthy Negro Killed—One Doctor and Dintist [sic], Brothers, Lose Lives in Race War.” Dallas Express, October 18, 1919, p. 13.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. “The Arkansas Race Riot.” N.p.: 1920. Online at https://archive.org/details/TheArkansasRaceRiot (accessed May 10, 2018).

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Low Villains and Wickedness in High Places: Race and Class in the Elaine Riots.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Autumn 1999): 285–313.

Whitaker, Robert. On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation. New York: Crown Publishers, 2008.

Work, Monroe N, ed. Negro Year Book: An Annual Encyclopedia of the Negro. 1918–1919. Tuskegee, AL: Negro Year Book Publishing Company, 1919.

Gwendolyn L. Shelton

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.