calsfoundation@cals.org

Steve Green (1862?–?)

In 1910, an Arkansas tenant farmer named Steve Green fled the state to Chicago, Illinois, after allegedly killing his employer, William Sidle (sometimes referred to as Seidel or Saddle), near Jericho (Crittenden County). He narrowly escaped extradition back to Arkansas after his case was taken up by prominent African Americans in Chicago, including Ida Wells-Barnett.

There is no record of Steve Green in Arkansas census records. According to an article written by W. E. B. Du Bois in the November 10, 1910, issue of The Crisis, Green was born in Tennessee in 1862 and was totally uneducated. There was an African American named Steve Green living in Civil District 15 in Shelby County, Tennessee, in 1900. He was born in March 1864 and married a woman named Millie in 1892. He was working as a day laborer with “stick lumber,” and she was working as a day laborer in the “gardens.” Neither one of the Greens could read or write, and they were renting their house. They must have later had children, because according to The Crisis at some point the Greens moved to Arkansas, where they felt there were better educational opportunities for their children.

While William Sidle had property near Jericho, he apparently lived in Memphis, Tennessee. His full name was William Malcolm Sidle. He was born on November 13, 1872, and died on March 1, 1910; he was buried in Bethlehem Cemetery near Capleville in Shelby County. His wife was Josephine Clement Sidle, the daughter of a prominent family in Crittenden County, Arkansas. They had two children.

According to a March 3, 1910, article in the Arkansas Gazette, Sidle had been having trouble with Green for some time. Although Green was considered a “peaceable negro,” he had proven “worthless, so far as work was concerned.” On the evening of March 1, Sidle, accompanied by his nephew Claude Burtinett, went to Green’s home to ask him to leave the farm or face a lawsuit. An argument ensued, and Green went into his house and returned armed with a rifle. He shot Sidle, who was reportedly unarmed, and when Burtinett attempted to help his uncle, Green managed to escape. Sidle died several hours later. A reward of $250 was offered, and W. S. Danner and T. H. Williford formed a posse to pursue and capture Green.

Reports differ as to the cause of the dispute. A different report in the Arkansas Gazette indicated that Green was working for Sidle when they argued over a boundary. Several other accounts indicate that, in February 1910, Sidle raised Green’s rent and warned him that if he left the farm no one else would hire him. Green did leave and was hired by a neighbor. Green told The Crisis a slightly different story: that his wife had died, and he was breaking up housekeeping but hired himself out to a neighbor for one day during the process. On March 1, 1910, Sidle came to Green’s home with friends. According to Green, Sidle warned him that “there was not room enough in Crittenden County for you and me to live,” pulled his pistol, and shot at him. Green ran into his house, got his rifle, and killed Sidle. According to Green, Sidle’s companions pursued the escaping Green, who hid in a tree until midnight. He then retrieved additional cartridges from another African American and walked for three days, eluding bloodhounds by walking through creeks, until he got to another town. There, friends gave him food and blankets, which he took to an island in the Mississippi River, where he hid out for three weeks. The friends also gave him $32, and he eventually went on foot and by rail to Chicago, where he arrived on August 12.

After his arrival in Chicago, Green befriended another African-American man, George Chivers, who ultimately turned him in to the police, who arrested and jailed him. According to the Arkansas Gazette, Sidle’s nephew went to Chicago to identify Green, and by August 21, the police reported that Green had confessed and that Crittenden County sheriff C. L. Lewis had set out for Chicago with extradition papers signed by Governor George Washington Donaghey. Chicago activist Ida Wells-Barnett, learning of Green’s situation, contacted Chicago attorneys E. H. Wright and W. C. Anderson, who petitioned the Cook County Circuit Court to block Green’s extradition. On August 23, the court granted a writ of habeas corpus, but for some reason the Chicago police turned Green over to Arkansas authorities anyway. According to the Chicago Defender, Arkansas officials told Green that “he was the most important Nigger in the United States since there was a reception committee of a thousand waiting for him in Arkansas with lighted fire.”

Green’s supporters, in an attempt to rescue him before he crossed the border into Missouri, then sent telegrams to stations along the railroad line. Alexander County sheriff Fred D. Nellis eventually found him in Cairo, Illinois, and sent him back to custody in Chicago. According to an August 28 article in the Cairo Bulletin, Sheriff Lewis of Crittenden County protested Nellis’s action, promising that he had enough men to protect Green and would also call out the militia if needed. He also offered to jail Green in Memphis if that would satisfy Illinois officials.

Fearing that Green would not receive a fair trial in Arkansas, Wright and the Reverend A. J. Carey, a prominent pastor in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), then proposed that he not be extradited until he had been proven guilty. They also noted flaws in Arkansas’s extradition order, including discrepancies in the date of the incident and “careless oversights and several crossed-out words.” In mid-September, the case came before Judge Richard Stanley Tuthill of the Cook County Circuit Court. Tuthill decided that the Chicago police had erred in turning Green over to Arkansas authorities and ordered his release. A week later, a mass meeting was held at Chicago’s Quinn Chapel AME Church to raise money to support Green’s cause. According to historians Susan D. Carle and Patricia A. Schechter, in early October, Green was taken to Canada to escape further prosecution. By October 15, authorities in Arkansas had petitioned Illinois governor Charles S. Deneen to surrender Green, and the following January, Arkansas governor George Donaghey reinstated the $200 reward for Green’s apprehension. There is no subsequent information available about what became of Green.

According to historian Karlos Hill, Green’s case shows the part African-American social networks in played in saving black suspects from mob violence. In addition, Green’s case is similar to a slightly later Arkansas case, that of Robert Lee Hill, who organized the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America in Phillips County and escaped to Kansas following the Elaine Massacre in 1919. Arkansas sought his extradition and he was arrested, but Kansas governor Henry Justin Allen refused to comply, fearing that Hill would not be safe if he returned to Arkansas. Charges against Hill were eventually dropped, and he was released from jail in October 1920.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Authorities Again Demand Steve Green.” Broad Ax, October 15, 1910, p. 2.

“Askansas [sic] Sheriff Protests against Negro Being Taken by Sheriff Nellis on Arrival Here.” Cairo Bulletin, August 28, 1910, p. 3.

Carle, Susan D. Defining the Struggle: National Racial Justice Organizing, 1880–1915. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Garb, Margaret. Freedom’s Ballot: African American Political Struggles in Chicago from Abolition to the Great Migration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Hill, Karlos. Beyond the Rope: The Impact of Lynching on Black Culture and Memory. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Schechter, Patricia A. “Ida B. Wells-Barnett and the Carceral State.” PDXScholar (Portland State University), History Faculty Publications and Presentations, Paper 16. September 28, 2012. Online at http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/hist_fac/16 (accessed January 26, 2018).

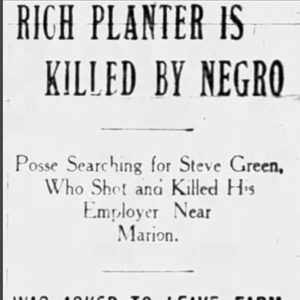

“Rich Planter is Killed by Negro.” Arkansas Gazette, March 3, 1910, p. 1.

“Stephen Green Discharged.” Arkansas Gazette, September 20, 1910, p. 1.

“Steve Green Liberated.” Chicago Defender, September 24, 1910, p. 1. Online at http://southernstudies.olemiss.edu/study-the-south/the-lynching-blues/assets/img/steve-green-liberated-large.jpg (accessed January 26, 2018).

“Steve Green Has Confessed.” Arkansas Gazette, August 21, 1910, p. 9.

“Steve Green Makes a Move.” Arkansas Gazette, August 24, 1910, p. 7.

“Steve Green’s Story.” The Crisis, November 1910, p. 14.

“Writ Issues in Chicago.” Arkansas Gazette, August 24, 1910, p. 7.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 William Sidle Killing Article

William Sidle Killing Article

William M. Sidle is my great-great-great-grandfather.