calsfoundation@cals.org

Stoneflies

Stoneflies (Phylum Arthropoda, Class Insecta, Order Plecoptera) are a group of aquatic insects well known to fishermen and biologists worldwide. The name Plecoptera means “braided-wings” from the Ancient Greek plekein and pteryx, which refers to “wing.” The name refers to the complex venation of their two pairs of wings, which are membranous and fold flat over their body. Generally, stoneflies are not strong fliers, and several species are entirely wingless. Stoneflies are called “indicator species” because finding them in freshwater environments generally indicates relatively good water quality, as they are quite intolerant of aquatic pollution. They are also prized and imitated by anglers as artificial tied-flies in trout fishing, particularly on Arkansas rivers such as the Eleven Point, Spring, and White. Approximately eighty species of stoneflies are known from Arkansas.

There are approximately 3,500 species in 300 genera and eighteen families of stoneflies described worldwide and nearly 600 species in North America, with new species occasionally being discovered, even in Arkansas. A well-known study of the stoneflies of the Interior Highlands (which includes parts of Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Illinois) found there to be eighty-eight species in eight families and twenty-four genera in this region.

One of the first to describe stoneflies was Thomas Say (1787–1834), who proposed four stonefly species and the genus in which they were originally placed. František (Franz) Klapálek (1863–1919), from what is now the Czech Republic, was the founder of Plecopterology; he described twenty-seven species of stoneflies of the family Perlidae from China. Four other leading stonefly experts of the past include William Edwin (Bill) Ricker (1908–2001), Per Simon Valdemar Brinck (1919–2013), Kenneth W. Stewart (1935–2012), and Stanley W. Szczytko (1949–2017). Some present stonefly biologists are Richard W. Baumann, R. Edward DeWalt, Boris C. Kondratieff, C. Riley Nelson, Barry C. Poulton, Bill P. Stark, and Peter Zwick. Most of the information to date on Arkansas stoneflies was provided by Poulton and his former mentor Stewart.

Stoneflies occur worldwide on every continent except Antarctica. They are found in both the Southern and Northern hemispheres. They are one of the most primitive groups of insects, with close relatives known from the Carboniferous and Lower Permian periods (from 350 to 300 million years ago) and with true stoneflies known from fossils only a little younger. The modern diversity of stoneflies present today is of Mesozoic origin (252 to 66 million years ago).

Taxonomically, the order Plecoptera is divided into two suborders: Antarctoperlaria (or “Archiperlaria”) and the Arctoperlaria. Because the Antarctoperlaria consists of the two most basal superfamilies of stoneflies, which do not seem to be each other’s closest relatives, the “Antarctoperlaria” are not considered a natural group. The Arctoperlaria have been divided into two infraorders, namely the Euholognatha (or Filipalpia) and the Systellognatha (also known as Setipalpia or Subulipalpia). There are three superfamilies: Nemouroidea (four families), Perloidea (three families), and Pteronarcyoidea (two families).

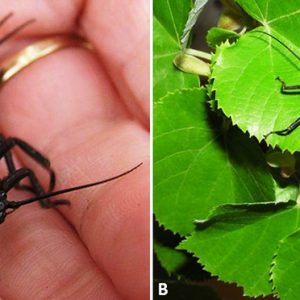

Stoneflies are hemimetabolous insects, meaning that they exhibit incomplete metamorphosis and lack the pupal stage. The nymph is similar in form to the adult and differs mainly in the incompletely developed condition of the wings and genitalia. The nymphs, or “naiads,” live in creeks, streams, rivers, and lakes that are well oxygenated and generally clear and cold. In New Zealand, there are a few species with terrestrial nymphs, but their habitats are very moist. Nymphs typically resemble wingless adults but often have external gills, which may be present on almost any part of the body. Amazingly, nymphs can get oxygen via diffusing through the exoskeleton (nymphal husk), or through gills situated behind the head, on the thorax, or around the anus. It is this requirement for well-oxygenated water that makes the species so sensitive to water pollution and, in effect, makes them important water quality indicators. Early instar nymphs are generally herbivorous and feed on detritus, diatoms, submerged leaves, and benthic algae but may shift to aquatic invertebrate prey in later instars.

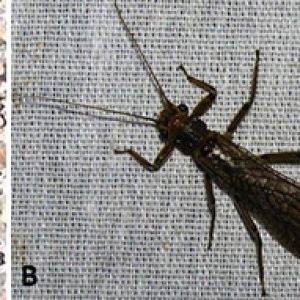

Adult stoneflies are terrestrial and typically only survive one to four weeks after transforming from nymphs and usually emerge only during certain times of the year (typically winter, November to March). Adult stoneflies have a rather generalized body anatomy with a relatively soft body; simple mouthparts with chewing mandibles; long, multiple-segmented antennae; large compound eyes; and two or three ocelli. Legs are large and end in two claws. Long, paired cerci project from the end of the abdomens of both adults and nymphs. Adults tend to be herbivorous if they feed at all, and because they are not strong fliers, adults tend to remain close to the stream or lake where they hatched.

In the suborder Arctoperlaria, the typical mating system includes vibrational (mostly drumming) signaling between the sexes, with males calling and searching and females conveying their stationary position with answers. This vibrational duetting is a species-specific fixed action behavior and is one of the most diverse and complex known in the class Insecta. The percussion, rubbing, and tremulation signals have been described for at least 121 North American and about twenty-nine European species. This stonefly vibrational communication is a species-specific behavior, which, along with morphology of genitalia, isolates and defines species.

Adults mate on vegetation, stones, bridges, and other physical situations. Gravid females may lay up to 1,000 eggs. Typically, the female will fly over the water surface and drop the eggs, although some are also known to hang on a rock or vegetated branch. Eggs adhere to rocks, benthic substrata, and other structures because they are covered with a sticky coating that prevents them from being swept away by the swift current. Hatching generally occurs in two to three weeks; however, some species undergo diapause, which is a situation whereby eggs remain dormant throughout a dry season and hatch only when conditions improve. After hatching, the nymphal stage may last from one to four years, depending on the species, and nymphs undergo from twelve to thirty-six molts before emerging and becoming an adult. Nymphs leave the water and attach to a fixed surface and molt one last time, becoming fully terrestrial adults.

The combination of mountainous topography, high gradient streams, varying flow permanence and temperatures, and warm climate make the Ozark–Ouachita mountains of Arkansas and its diverse Plecoptera fauna unique among the natural physiographic regions of North America. Several endemic stoneflies occur in the state, most only from their type locality. They include Allocapnia warreni from Washington County, A. ozarkana from Madison County, A. oribata from Searcy County, Alloperla ouachita from Hot Spring and Montgomery counties, A. caddo from Garland and Perry counties, Isoperla szczytkoi from Logan County, Zealeuctra wachita from Polk and Scott counties, and Leuctra paleo from Columbia and Dallas counties.

The International Society of Plecopterologists publishes an annual newsletter called Perla. Illiesia is the international journal of stonefly research.

For additional information:

Allen, Robert T. “Insect Endemism in the Interior Highlands of North America.” Florida Entomologist 73 (1990): 539–569.

Anderson, J. E., ed. Arkansas Wildlife Action Plan. Little Rock: Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, 2006.

Campbell, Ian C. Mayflies and Stoneflies: Life History and Biology. Proceedings of the 5th International Ephemeroptera Conference and the 9th International Plecoptera Conference. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1990.

Cummins, Kenneth W., and Ronald W. Merritt. Ecology and Distribution of Aquatic Insects. In An Introduction to the Aquatic Insects of North America, 3rd ed., edited by Ronald W. Merritt and Kenneth W. Cummins. Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1996.

DeWalt, R. Edward, Michael D. Maehr, U. Neu-Becker, G. Stueber, and David C. Eads. Plecoptera Species File Online, Version 5.0/5.0, 2018. Online at http://plecoptera.speciesfile.org/HomePage/Plecoptera/HomePage.aspx (accessed November 30, 2018).

Ernst, M. R., Barry C. Poulton, and Kenneth W. Stewart. “Neoperla (Plecoptera: Perlidae) of the Southern Ozark and Ouachita Mountain Region, and Two New Species of Neoperla.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 79 (1986): 645–661.

Feminella, Jack W. “Comparative Feeding Ecology of Leaf Pack-Inhabiting Systellognathan Stoneflies (Plecoptera) in the Upper Little Missouri River, Arkansas.” MS thesis, University of North Texas, 1983. Online at http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc503884/m1/1/ (accessed November 30, 2018).

Feminella, Jack W., and Kenneth W. Stewart. “Diet and Predation by Three Leaf-Associated Stoneflies (Plecoptera) in an Arkansas Mountain Stream.” Freshwater Biology 16 (1986): 521–538.

McAllister, Chris T., Henry W. Robison, and Michael E. Slay. “The Arkansas Endemic Fauna: An Update with Additions, Deletions, a Synthesis of New Distributional Records, and Changes in Nomenclature.” Texas Journal of Science 61 (2009): 203–218.

Morse, John C., W. Patrick McCafferty, Bill P. Stark, and Luke M. Jacobus, eds. Larvae of the Southeastern USA Mayfly, Stonefly, and Caddisfly Species (Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera). Clemson, SC: Clemson University Public Service Publishing, 2017.

Nelson, C. Riley, Richard W. Baumann, and J. J. Lee. “New Morphological Observations and Phylogenetic Placement of Capnia shasta (Plecoptera: Capniidae).” Illiesia 9 (2013): 122–125.

Poulton, Barry C. “The Stoneflies (Plecoptera) of the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains.” PhD diss., University of North Texas, 1989. Online at https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc331637/?q=Poulton%2C%20Barry (accessed November 30, 2018).

Poulton, Barry C., and Kenneth W. Stewart. “The Stoneflies of the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains (Plecoptera).” Memoirs of the American Entomological Society 38 (1991): 1–116.

———. “Three New Species of Stoneflies (Plecoptera) from the Ozark-Ouachita Mountain Region.” Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 89 (1987): 296–302.

Ricker, William E. “Systematic Studies in Plecoptera.” Indiana University Publications, Science Series 18 (1952): 1–200.

Robison, Henry W., and Robert T. Allen. Only in Arkansas: A Study of the Endemic Plants and Animals of the State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Robison, Henry, Chris McAllister, Christopher Carlton, and Robert Tucker. “The Arkansas Endemic Biota: With Additions and Deletions.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 62 (2008): 84–96. Online at http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol62/iss1/14/ (accessed November 30, 2018).

Robison, Henry W., and Kenneth L. Smith. “The Endemic Flora and Fauna of Arkansas.” Proceedings of the Arkansas Academy of Science 36 (1982): 52–57. Online at http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol36/iss1/17/ (accessed November 30, 2018).

Ross, H. H., and William E. Ricker. “The Classification, Evolution, and Dispersal of the Winter Stonefly Genus Allocapnia.” University of Illinois Biological Monographs 45 (1971): 1–166.

Sandberg, J. B., and Kenneth W. Stewart. “Continued Studies of Vibrational Communication (Drumming) Of North American Plecoptera.” Illiesia 2 (2006): 1–14.

Sheldon, A. L., and S. A. Grubbs. “Distributional Ecology of a Rare, Endemic Stonefly.” Freshwater Science 33 (2014): 1119–1126.

Sheldon, A. L., and Melvin L. Warren, Jr. “Filters and Templates: Stonefly (Plecoptera)/Richness in Ouachita Mountains Streams, U.S.A.” Freshwater Biology 54 (2009): 943–956.

Stark, Bill P. “Additional Characters in Perlesta baumanni Stark (Plecoptera: Perlidae), with Notes on Other Ouachita Mountain Species.” Illiesia 3 (2007): 43–45.

Stark, Bill P., Kenneth W. Stewart, and Jack Feminella. “New Records and Descriptions of Alloperla (Plecoptera: Chloroperlidae) from the Ozark–Ouachita Region.” Entomological News 94 (1983): 55–59.

Stark, Bill P., Kenneth W. Stewart, Stanley W. Szczytko, and Richard W. Baumann. “Common Names of Stoneflies (Plecoptera) from the United States and Canada.” Ohio Biological Survey Notes 1 (1998): 1–18.

Stark, Bill P., Stanley W. Szczytko, and Richard W. Baumann. “North American Stoneflies (Plecoptera): Systematics, Distribution, and Taxonomic References.” Great Basin Naturalist 46 (1986): 383–397.

Stewart, Kenneth W., G. L. Atmar, and B. M. Solon. “Reproductive Morphology and Mating Behavior of Perlesta placida (Plecoptera: Perlidae).” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 62 (1969): 1433–1438.

Stewart, Kenneth W., Richard W. Baumann, and Bill P. Stark. “The Distribution and Past Dispersal of Southwestern United States Plecoptera.” Transactions of the American Entomological Society 99 (1974): 507–546.

Stewart, Kenneth W., and Bill P. Stark. Nymphs of North American Stonefly Genera (Plecoptera), 2nd ed. Columbus: Caddis Press, 2002.

———. Plecoptera. In An Introduction to the Aquatic Insects of North America, 4th ed. Edited by Ronald W. Merritt, Kenneth W. Cummins, and M. B. Berg. Dubuque: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company, 2008.

Tipton, Zachary. “Patterns in Winter Stonefly Distribution along a River Continuum and Land-Use Gradient in Northwest Arkansas Streams.” MS thesis, University of Arkansas, 2023. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/5103/ (accessed February 21, 2024).

Zeigler, D. D., and Kenneth W. Stewart. “Drumming Behavior of Eleven Nearctic Stonefly (Plecoptera) Species.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America 70 (1977): 495–505.

Zwick, Peter. “Phylogenetic System and Zoogeography of the Plecoptera.” Annual Review of Entomology 45 (2000): 709–746.

Henry W. Robison

Sherwood, Arkansas

Chris T. McAllister

Eastern Oklahoma State College

Science and Technology

Science and Technology Stoneflies

Stoneflies  Stoneflies

Stoneflies

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.