calsfoundation@cals.org

Suckers

aka: Catostomid Fishes

Suckers belong to the Family Catostomidae, Order Cypriniformes, and Class Actinopterygii. There are about seventy-two species and thirteen extant genera of these benthic (bottom-dwelling) freshwater fishes. In Arkansas, there are eighteen species in eight genera. Suckers are Holarctic in distribution and primarily native to North America north of Mexico, but the longnose sucker (Catostomus catostomus) occurs in both North America and northeastern Siberia from Alaska, and the Asiatic Sucker (Myxocyprinus asiaticus) is found in the Yangtze River basin in China. Sucker-like fossils are known from Eocene epoch (56 to 33.9 million years ago) deposits from central Asia, and the fossil genus Amyzon, with Ictiobus and Myxocyprinus affinities, occurs in middle Eocene and Oligocene Epoch (33.9 to 23 million years ago) deposits in western North America (Colorado and Utah). There are three additional extinct genera including Jianghanichthys, Plesiomyxocyprinus, and Vasnetzovia.

The harelip sucker, Moxostoma lacerum (formerly Lagochila lacera), was first collected in 1859 and not formally described until 1877 by David Starr Jordan (1851–1931) and Alembert W. Brayton (1848–1926); it was last collected in 1893 and is considered extinct. Interestingly, it was one of the most common suckers in streams of the Tennessee River region in 1877. The former range encompassed eight states including the upper White River near Eureka Springs (Carroll County), where it was found in 1884. Its demise is thought to have been caused by the systematic plowing of prairies and logging of forests, which resulted in unprecedented erosion and a catastrophic siltation of once crystal-clear, pristine streams in which it formerly thrived.

Suckers get their common name from their mouth, which is located on the underside of its head (subterminal), with thick, fleshy, protrusible lips, and toothless jaws. They typically also have cycloid scales (except on their heads), eighteen principal caudal fin rays, ten or more dorsal fin rays, a two- or three-chambered gas bladder, and a single row of twenty or more pharyngeal teeth (on long pharyngeal bone in the throat) that gradually decrease in size. Most suckers are less than 60 cm (2.0 ft.) in length, but some species in the genera Ictiobus and Myxocyprinus surpass 100 cm (3.3 ft.).

As adults, catostomids are most often found in medium to large rivers, but may be found in any freshwater watershed. However, each kind of sucker has its own habitat preference. Their mouth is adapted for sucking food (like a vacuum cleaner) from the bottom. They are omnivorous, with food items ranging from detritus and bottom-dwelling organisms (such as crustaceans, worms, and larval aquatic insects) to surface insects and small fishes, although vegetable matter is often consumed. However, several species are specialist feeders on mollusks.

Reproductively, spawning in suckers is “random” with up to 300,000 eggs being scattered about the aquatic environment, except in the river redhorse (Moxostoma carinatum), in which the male constructs a nest-like depression in low gravel shoals. The fertilized eggs sink to the bottom, are entrapped in the spaces between gravel, or adhere to gravel. In addition, the chubsucker males (genus Erimyzon) defend territories. Spawning generally occurs from early spring to early summer, with the largest species frequently migrating up smaller tributaries. Males of some species develop large scattered and tiny granular nuptial tubercles on their bodies during the reproductive season.

Suckers are not usually fished recreationally with rod and reel and not highly prized in North America, although they are fairly popular with spear fishermen or those who snag, gig, or trap them (especially during spring spawning runs). Native Americans are known to have used traps for easy harvest such as V-shaped piles of rocks placed in streams to funnel and concentrate migrating suckers. Suckers have a firm white flesh, and in some regions, such as the Ozark Highlands, they are a common food fish with excellent flavor. They can be canned, smoked, pickled, or fried, but small incisions often must be made in the flesh (termed “scoring”) before frying to allow small internal bones (epineurals) to be edible. In Arkansas, buffalofishes (Ictiobus spp.) comprise the largest biomass of the annual catch by commercial fishermen in the state.

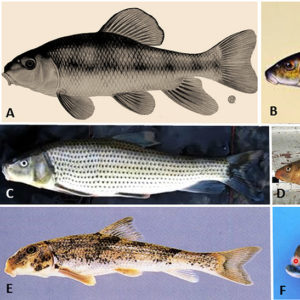

Buffalofishes possess a long, falcate dorsal fin with twenty-four to thirty-one rays and a terminal or inferior/horizontal mouth. They are generally gray to dark olive in color with a semicircle subopercle that is broadest at the middle. Dorsal fin rays number 23 to 32, and their pelvic and anal rays number eighteen or more. There are three species in Arkansas: the smallmouth buffalo (Ictiobus bubalus), bigmouth buffalo (I. cyprinellus), and black buffalo (I. niger). The Arkansas state record for the largest catostomid in the state caught by rod and reel is a black buffalo at 41.7 kg (92 lbs.) caught in Lake Maumelle in 2001. In addition, a smallmouth buffalo caught in 1984 at Lake Hamilton was 91.4 cm (3 ft.) long and weighed 30.8 kg (68 lbs.). All three are large catostomids that are widespread in the state in both large and smaller rivers, except for I. niger, which occurs sporadically in larger rivers of Arkansas. They are also very successful in reservoirs and some natural lakes.

Suckers of genus Carpiodes also possess a long, falcate dorsal fin but with twenty-three to thirty rays. They are generally dull gray or brown dorsally, silver on sides, and with a subtriangular subopercule that is broadest below middle. In addition, they often have white to orange pelvic fins that are not covered with black specks and a nipple-like projection on their lower lip. In Arkansas, there are three species, the river carpsucker (Carpiodes carpio), the similarly sized quillback (C. cyprinus), and the smaller is the highfin carpsucker (C. velifer). On average, these are small suckers that often weigh between 0.45 to 1.4 kg (1 and 3 lbs.), but larger ones over 6 lbs. are not common. The largest Carpiodes ever caught by unrestricted tackle (other than rod and reel) in Arkansas was a quillback from the Arkansas River in 2016 that weighed 1.4 kg (3 lbs., 3 oz.). The river carpsucker is the most abundant carpsucker occurring in all the major river drainages but tends to avoid upland streams; the quillback is found irregularly in the state in the Arkansas and White rivers; and the Highfin Carpsucker, which is much less tolerant of turbidity and siltation, is considered rare but is found occasionally in the upper Black and White rivers and also in the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers.

There are two members of the chubsucker genus Erimyzon in Arkansas: the western creek chubsucker (Erimyzon claviformis) and lake chubsucker (E. sucetta). These are relatively small (102 to 178 mm long, or 4 to 7 in.) but are robust elongate fishes that possess large fins, no lateral line, a dorsal fin with nine to ten rays (E. claviformis) or eleven to twelve rays (E. sucetta), and an anal fin with seven rays. They are mostly dark bronze, gold, or olive above, grading to golden-yellow on their sides. The western creek chubsucker is widespread in Arkansas, occurring in all major drainages except those in the higher elevations in the northwestern corner of the state, whereas E. sucetta is a lowland species confined to the Gulf Coastal Plain physiographic region of Arkansas. They prefer clear, often vegetated, low-gradient streams, lakes, and oxbows.

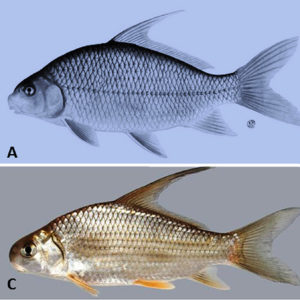

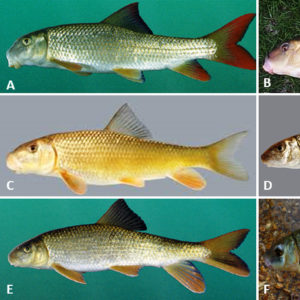

The redhorses, genus Moxostoma, comprise the most speciose genus of suckers in eastern and central North America and are represented by six species in the state, including the silver redhorse (Moxostoma anisurum), river redhorse (M. carinatum), golden redhorse (M. erythrurum), black redhorse (M. duquesnei), pealip redhorse (M. pisolabrum), and blacktail redhorse (M. poecilurum). These are robust, long, slender suckers with a large horizontal mouth and thick papillose or plicate lips with a groove between their upper lip and snout. They possess a complete lateral line with nine to seventeen dorsal rays and seven anal rays.

Some species are difficult to distinguish from one another, and comparison of their lower lip and counts of their lateral line scales will often serve to help separate the species in Arkansas. However, juvenile redhorses are notoriously difficult to identify, and their preliminary identification should always be confirmed by an expert. Habitats range from big rivers to sluggish creeks to areas with swift current in small creeks. Redhorses generally range from 0.45 to 4.5 kg (one to ten lbs.) in weight and 38 to 66 cm (15 to 26 in.) long. The state record for the largest Moxostoma caught in Arkansas on unrestricted tackle is a M. carinatum that weighed 4 kg (9 lbs.) caught in Lake Ouachita in 2013. Of the six redhorses found in Arkansas, the silver redhorse and pealip redhorse have the most restricted distribution, with the former found in the White River and the latter in the Arkansas and White rivers. As such, M. anisurum is considered critically imperiled (S1), and M. pisolabrum is listed as imperiled in the state by NatureServe.

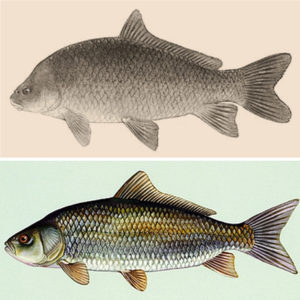

The white sucker (Catostomus commersonii) is a slender terete fish that possesses a deep median lower lip notch with zero to three rows of papillae at the middle of the lower lip and two to six papillae on the upper lip. They are olive-brown to black above, often with very small dusky-edged scales and ten to twelve dorsal rays. This sucker ranges in size up to 46 cm (18 in.) long and weighs between 2.7 to 3.2 kg (6 to 7 lbs.). In Arkansas, C. commersonii is not common and reaches its southernmost range in the northern boundary of the state in the upper Arkansas, Illinois, and White river systems. It prefers spring pools and spring-fed feeder creeks with large amounts of submerged vegetation and gravel bottoms. In some parts of its range, juvenile white suckers are often used as bait.

The blue sucker (Cycleptus elongatus) bears little resemblance to any other North American catostomid species. It has a long, compressed body; small head; long caudal peduncle; and long falcate dorsal fin with twenty-eight to thirty-seven rays. This sucker also has a blunt snout that overhangs the small horizontal mouth containing many blunt papillae on the lips. They are olive-blue or dark blue-gray above, blue-white below, with dark blue-gray fins. It ranges in size from 64 to 100 cm (25 to 40 in.) and weighs between 2.7 to 6.8 kg (6 to 15 lbs.). This fish prefers rivers with strong swift current in deep chutes and main channels of medium to large rivers over bedrock, sand, and gravel. In Arkansas, C. elongatus is mostly restricted to the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers, with additional records from the Black, Little Red, Red, and Spring rivers. This sucker is listed as S2 (imperiled) in the state according to NatureServe.

The northern hogsucker (Hypentelium nigricans) is an odd-looking fish with a rectangular concave head and a long, blunt snout with large fleshy lips with many large papillae. Its body is wide in front, abruptly tapering behind the dorsal fin, and there are three to six dusky or brown mottled saddles on the sides. Coloration is dark-olive or bronze to red-brown above, pale yellow or white below, with olive to orange fins. The dorsal fin is short, falcate, and contains ten to twelve rays and there are seven anal rays. The maximum total length and weight of H. nigricans is about 57 cm (22.5 in.) and 1.9 kg (4.3 lbs.). This fish inhabits most of the upland streams of the Ozark and Ouachita Highlands. It occurs in clear, permanent streams with gravel or rocky substrates, where it prefers deep riffles, raceways, or pools having a current. It is very intolerant of pollution, and its occurrence in a stream generally predicts the water is clean and unpolluted. Other fish may benefit by feeding on insects disrupted from the substrate by a foraging H. nigricans.

The spotted sucker (Minytrema melanops) is the only species in the genus. It is a moderately slim-bodied fish that possesses a long, redhorse-like body with eight to twelve parallel rows of dark spots on its back and sides. This sucker has a small, horizontal mouth with thin plicate lips. Coloration is dark green or olive-brown above, paler below, and yellow to brown on its sides. There are eleven to thirteen dorsal fin rays and seven anal rays. This fish has a maximum reported size of 45.7 cm (18 in.) and weight of 0.9 kg (2 lbs.). Minytrema melanops ranges over most of the state but is nearly absent from the upper White River drainage. It occurs in clear to slightly turbid low gradient streams and pools with submerged aquatic vegetation, detritus, and soft substrates.

Catostomid fishes are excellent hosts of various parasites including protists, monogeneans, trematodes, cestodes, nematodes, acanthocephalans, and crustaceans. In Arkansas, various acanthocephalans have been reported from M. carinatum, M. duquesnei, and C. velifer, all collected from the White River below Lock and Dam No. 1 in Independence County. In 2017, several parasites were reported in M. pisolabrum from adjacent Oklahoma.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Endangered, Threatened, Regulated, and Species of Greatest Conservation Need.” Little Rock: Arkansas Game & Fish Commission, 2016.

Branson, Branley A. “Comparative Cephalic and Appendicular Osteology of the Fish Family Catostomidae. Part I, Cycleptus elongatus (Lesueur).” Southwestern Naturalist 7 (1962): 81–153.

Bruner, John C. “Comments on the Genus Amyzon (Family Catostomidae).” Journal of Paleontology 654 (1991): 678–686.

Burr, Brooks M., and Richard L. Mayden. “A New Species of Cycleptus (Cypriniformes: Catostomidae) from Gulf Slope Drainages of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, with a Review of Distribution, Biology and Conservation Status of the Genus.” Bulletin Alabama Museum of Natural History 20 (1999): 19–57.

Cavender, T. M. “Review of the Fossil History of North American Freshwater Fishes.” In The Zoogeography of North American Freshwater Fishes, edited by C. H. Hocutt and Edward O. Wiley. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1986.

Chen, Wei-Jen, and Richard L. Mayden. “Phylogeny of Suckers (Teleostei: Cypriniformes: Catostomidae): Further Evidence of Relationships Provided by the Single-Copy Nuclear Gene IRBP2.” Zootaxa 3586 (2012): 195–210.

Doosey, M. H., Henry L. Bart Jr., K. Saitoh, and M. Miya. “Phylogenetic Relationships of Catostomid Fishes (Actinopterygii: Cypriniformes) Based on Mitochondrial ND4/ND5 Gene Sequences.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 54 (2010): 1028–1034.

Frimpong, E. A., and P. L. Angermeier. “FishTraits: A Database of Ecological and Life History Traits of Freshwater Fishes of the United States.” Fisheries 34 (2009): 487–493.

Hoffman, Glenn L. Parasites of North American Freshwater Fishes. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Lee, David S., Carter R. Gilbert, Charles H. Hocutt, Robert E. Jenkins, Donald W. McAllister, and Jay R. Stauffer Jr. Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes. Raleigh: North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, 1980.

McAllister, Chris T., Michael A. Barger, Thomas J. Fayton, Matthew B. Connior, David A. Neely, and Henry W. Robison. “Acanthocephalan parasites of select fishes (Catostomidae, Centrarchidae, Cyprinidae, Ictaluridae), from the White River Drainage, Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 69 (2015): 132–134. Online at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol69/iss1/25/ (accessed July 18, 2018).

McAllister, Chris T., Donald G. Cloutman, Anindo Choudbury, and Henry W. Robison. “Noteworthy Records of Helminth (Monogenoidea, Cestoda, Nematoda) and Crustacean (Copepoda) Parasites from Pealip Redhorses, Moxostoma pisolabrum (Catostomidae), from Oklahoma.” Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science 97 (2017): 50–53.

McAllister, Chris T., Dennis J. Richardson, Michael A. Barger, Thomas J. Fayton, and Henry W. Robison. “Acanthocephala of Arkansas, Including New Host and Geographic Distribution Records from Fishes.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 79 (2016): 155–160. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol70/iss1/26/ (accessed July 18, 2018).

McAllister, Chris T., Henry W. Robison, and Kenneth E. Shirley. “Two Noteworthy Geographic Distribution Records for the White Sucker, Catostomus commersonii (Cypriniformes: Catostomidae), from Northern Arkansas.” Texas Journal of Science 62 (2010): 237–240.

McAllister, Chris T., Wayne C. Starnes, Henry W. Robison, Robert E. Jenkins, and Morgan E. Raley. “Distribution of the Silver Redhorse, Moxostoma anisurum (Cypriniformes: Catostomidae), in Arkansas.” Southwestern Naturalist 54 (2009): 514-518.

Nelson, Joseph S., Terry C. Grande, and Mark V. H. Wilson. Fishes of the World. 5th ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2016.

Page, Lawrence M., and Brooks M. Burr. Peterson Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America North of Mexico. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011.

Robison, Henry W., and Thomas M. Buchanan. Fishes of Arkansas. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Robison, Henry W., Chris T. McAllister, and Kenneth E. Shirley. “The Fishes of Crooked Creek (White River Drainage) in Northcentral Arkansas, with New Records and a List of Species.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 65 (2011): 111–116. Online at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol65/iss1/16/ (accessed July 18, 2018).

Ross, Stephen T. Ecology of North American Freshwater Fishes. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

Shirley, Kenneth E., Chris T. McAllister, Henry W. Robison, and Thomas M. Buchanan. “The Blue Sucker, Cycleptus elongatus (Lesueur) (Cypriniformes: Catostomidae) From the Transition Zone of the Upper and Lower White River, Arkansas.” Texas Journal of Science 65 (2013): 41–47.

Smith, G. R. “Phylogeny and Biogeography of the Catostomidae, Freshwater Fishes of North America and Asia.” In: Systematics, Historical Ecology and North American Freshwater Fishes, edited by Richard L. Mayden. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992.

Uyeno, T., and G. R. Smith. “Tetraploid Origin of the Karyotype of Catostomid Fishes.” Science 175 (1972): 644–646.

Warren, Melvin L., Jr., and Brooks M. Burr. Freshwater Fishes of North America. Vol. 1. Petromyzontidae to Catostomidae. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014.

Chris T. McAllister

Eastern Oklahoma State College

Science and Technology

Science and Technology Suckers of Arkansas

Suckers of Arkansas  Suckers of Arkansas

Suckers of Arkansas  Suckers of Arkansas

Suckers of Arkansas  Suckers of Arkansas

Suckers of Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.