calsfoundation@cals.org

Frank Harris (Lynching of)

On August 18, 1871, an African-American man named Frank Harris was lynched at Wittsburg (Cross County) for allegedly murdering a twelve-year-old white girl named Isy Sanders, the daughter of Isaiah Sanders.

According to the 1870 census, farmer I. Sanders was living near Wittsburg with his wife K. Sanders, their daughter S. J. (age twelve), and two sons, I. L. G. (age eleven) and M. C. (age five). That same year, a twenty-five-year-old African-American farm laborer identified as F. Harris was also living with his wife near Wittsburg, only two households away from the Sanders family. In addition, there was another African American named Frank Hare living not far away near Wittsburg with his wife M. Hare and four children between the ages of nine and sixteen. Either of these men may have been the alleged perpetrator, although the former did live closer to the Sanders family.

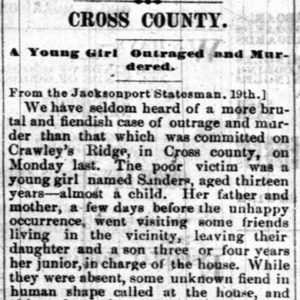

According to the Arkansas Gazette, the attack occurred on August 14. The Gazette reports differ in their accounts of the story. One account says that Isaiah Sanders and his wife apparently left their daughter Isy and a younger brother in charge of the house while they went to visit friends in the area. Another says that Mrs. Sanders was called away to tend to a sick friend and left Isy alone at home. In any case, while they were away, “some unknown fiend in human shape” came to the house and “either decoyed or forcibly dragged the helpless child to a dense undergrowth in a ravine, about three hundred yards distant.” There, he reportedly raped her and then stabbed her to death. Some neighbors heard screams, “but supposing it was children at play, passed it unheeded.” When Isy’s parents returned home that evening and found her missing, they enlisted the neighbors and began to search for her. Her body was found in the ravine around daylight the following morning.

Following a coroner’s inquest, “a committee of the most discreet citizens” began to search for evidence to identify the perpetrator. By Thursday, they had discovered that there were tracks leading from the murder site to the field where Harris had been working, and that the size and a crease in the heel of one of the tracks matched Frank Harris’s shoes. Harris was apparently not at work at the time of the incident and could give no explanation. He was arrested, and apparently a “jury” of twelve men was assembled on the spot. They concluded that he was guilty and decided that he should be hanged. However, “through the influence of some of the most influential men of the county,” the surrounding crowd was queried and decided that he should have a lawful trial.

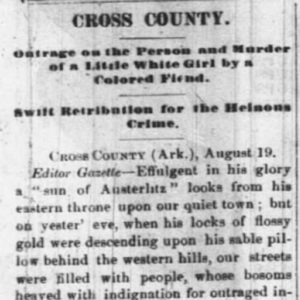

Harris was taken to Wittsburg and put in jail there under strong guard, and on Friday, August 18, he was brought “before an investigating court for commitment.” The trial was attended by between 400 and 500 citizens, both black and white. Proceedings ended late in the afternoon, to reconvene the following morning for the examination of eight additional witnesses, although most thought that there was already enough evidence to hang him. A deputy sheriff and a guard managed to shepherd Harris out of the courthouse, but they were barely outside when “a suppressed murmur, like the pent-up but smothered muttering of a volcano, ran through the crowd, and almost without a word, and in less than half a minute, two-thirds of that mass of men had hurled themselves like an avalanche upon the prisoner and guards and bore them back.” A mob of about 200 men took Harris to the scene of the crime and hanged him from a tree. The Gazette reported that this mob included both black and white participants.

Expressions of outrage abounded. This included Harris’s wife, who, when consulted, said that if he was guilty he should be punished. Harris never confessed to the crime, but, as one account stated, “All agree that he was guilty.” Many others, however, felt that “inasmuch as it was agreed to give him a trial, it should have been finished.” The Gazette expressed a sentiment typical with such events, concluding that “the people of Cross county are noted as law-abiding, good citizens, and we regret that they should think it necessary to resort to lynch-law—but however much we deplore it, we do not wonder that they should let their feelings get the better of their judgment and take the law in their own hands when the circumstances were of such an appalling character.”

For additional information:

“Cross County.” Arkansas Gazette, August 23, 1871, p.1.

“Cross County.” Arkansas Gazette, August 24, 1871, p. 1.

“Mob Law.” Arkansas Gazette, August 24, 1871, p. 2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Frank Harris Lynching Article

Frank Harris Lynching Article  Frank Harris Lynching Article

Frank Harris Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.