calsfoundation@cals.org

Temperate Basses

aka: Moronids

The temperate basses are freshwater, brackish water, and marine species belonging to the Order Perciformes and Family Moronidae. They are represented by two genera and six species—the North American and northern African Morone (four species) and European Dicentrarchus (two species). In North America, two popular freshwater game fish species, white bass (Morone chrysops) and yellow bass (M. mississippiensis), are native, whereas two others, the anadromous striped bass (M. saxatilis) and brackish water white perch (M. americana), have been successfully introduced into several U.S. states. In Arkansas, M. chrysops, M. mississippiensis, M. saxatilis and, rarely, M. americana are found in various watersheds. In addition, hybrid M. saxatilis × M. chrysops have been cultured and stocked in several Arkansas reservoirs.

Morphologically, in general, moronids are deep-bodied compressed fishes with two dorsal fins; the first usually has nine spines, and the second has one spine with eleven to fourteen rays. They also have three anal spines, ctenoid scales, a complete lateral line, a pseudobranch (small gill) on the underside of the gill cover, and a strongly saw-toothed preopercle (bone at rear of cheek).

White Bass

White bass (also commonly called sand bass) is a medium-sized widespread moronid species that ranges from the southern Great Lakes, Mississippi River basin, and Gulf Coastal drainages from the Mississippi River west through the Rio Grande of Texas and New Mexico. In Arkansas, M. chrysops is widely distributed in the state and occurs in all major drainages, especially large rivers and impoundments.

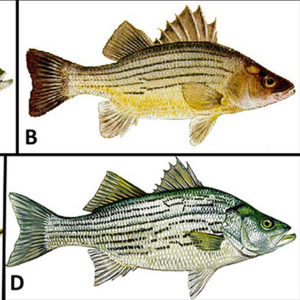

A photograph of M. chrysops appears on the cover of the 1988 Fishes of Arkansas by Henry W. Robison and Thomas M. Buchanan. It is a silver-white fish with four to seven faint longitudinal stripes on the sides, and the first and second dorsal fins are entirely separate. The first dorsal possesses nine spines, and the second dorsal fin contains one spine and thirteen to fifteen soft rays. The anal fin has eleven to thirteen anal rays, with three graduated spines, the first shorter than the second, and the second shorter than the third. This bass has one to two tooth patches near the midline toward the back of the tongue. Adult M. chrysops are generally 254 to 381 mm (10 to 15 in.) long and average about 0.5 kg (1 lb.) in weight. The Arkansas state rod and reel record was set by a 2.4 kg (5 lb., 6 oz.) white bass from the Mississippi River.

White bass inhabit large reservoirs and moderately sized rivers. They are found in both current and backwater areas in clear water over a rock or sand substrate. However, this bass is intolerant of turbidity. When mating in the late winter and early spring, they often migrate into creeks, shallow rivers, and streams.

The reproductive season for white bass is mid-March to late May in optimal water temperatures of 12 to 20°C (54 to 68°F). Even if spawning white bass are moved to a different part of the same lake, they are known to find their home spawning ground. Spawning occurs during daylight in moving water in tributaries, but they can also spawn in windswept lake shores. Females release 242,000 to 933,000 eggs in shallow water that then stick to the surface of objects (plants, submerged logs, gravel, or rocks). When trying to locate a female with which to mate, males will bump against a female’s abdominal area. The female will then rise closer to the surface and begin spinning and releasing eggs. Several males that have stayed in the area will be able to fertilize the eggs the female releases. After the spawn, the parents move to deeper water, and there is no parental care for the young. Hatchling and juvenile fish live in shallow water for a while and, as they grow, will move to deeper water.

White bass are visual sight predators that tend to be active open-water feeders that travel in large schools in search of prey in early morning and late afternoon. They feed on small crustaceans (copepods, Daphnia, and Leptodora water fleas) and aquatic insects, but larger fish seem to prefer eating fish, particularly shad (Dorosoma spp.). Specimens studied for food habits from Beaver Reservoir in Arkansas were reported to feed mostly on shad, followed by centrarchids (sunfishes) and cyprinids (minnows).

Yellow Bass

The yellow bass (Morone mississippiensis) may be found in somewhat clearer waters of the Mississippi River from Minnesota south to the Gulf Coastal drainages of Louisiana and west to the Galveston Bay drainage in Texas. In Arkansas, M. mississippiensis is found primarily in the Arkansas, Mississippi, Ouachita, Red, St. Francis, and White rivers. The yellow bass can also occur in pools and backwaters of large sluggish rivers and oxbow lakes surrounding these rivers, especially in areas with dense vegetation and little turbidity. The largest Arkansas populations of yellow bass occur in Lake Chicot (Chicot County), Horseshoe Lake (Crittenden County), and Mallard Lake (Mississippi County). Hybrids of M. chrysops × M. mississippiensis have been reported in Texas and Wisconsin.

Yellow bass are deep-bodied fishes that possesses five to seven black distinct stripes laterally along the sides, and the bottom few are often broken or disrupted (offset) anterior to the origin of the anal fin. This bass has nine to ten anal rays, eleven to twelve dorsal fin rays, and fifteen to seventeen pectoral fin rays. It does not have a tooth patch near the midline toward the back of the tongue. The coloration is usually a dark olive green, and the abdomen has brassy yellow sides. Maximum size is about 1.02 kg (2 lbs., 4 oz.), while the Arkansas rod and reel record was set by a 0.96 kg (2 lb., 2 oz.) fish collected from Gillham Lake (Sevier County).

The food habits of adult M. mississippiensis include small fishes (shad and silversides), with the remainder of their diet consisting of small crustaceans and other zooplankton. Juvenile yellow bass feed almost exclusively on aquatic insects (midge larvae) and microcrustaceans.

Yellow bass reproduce in a manner similar to that of white bass, where spawning occurs during the spring (April and May), with fish swimming into tributary streams to make spawning runs. Spawning usually occurs in moderately shallow clearer waters with vegetation.

Unlike other moronids, the yellow bass is not popular as a gamefish because of its small size. However, it is quite edible and is commonly eaten in its range, particularly in watersheds in Tennessee. They can be caught by anglers fishing with minnows or crappie jigs.

Striped Bass

The striped bass (also commonly called the striper) is an anadromous species that migrates between fresh and marine waters and is found primarily along the Atlantic coastline of North America from the St. Lawrence River into the Gulf of Mexico to Louisiana. Stripers have been introduced by state game and fish commissions into the Pacific Coast of North America and into several large reservoir impoundments across the United States for the purposes of recreational fishing and as a predator to control populations of gizzard shad (Dorosoma cepedianum). In Arkansas, M. saxatilis was widely introduced into reservoirs first in 1956 in Lake Ouachita followed by other impoundments, including Lake Greeson (in 1957), Lake Hamilton, Beaver Reservoir, Lake Greeson, Lake Norfork, and Greers Ferry. They are also found in the Arkansas and Red rivers.

Striped bass have a slender body with six to nine distinct black horizontal stripes, several extending to the caudal fin, and one to two distinct tooth patches near the midline toward the back of the tongue. The first dorsal fin has nine spines, the second dorsal fin has twelve soft rays, and the anal fin has three graduated spines—the first shorter than the second, and the second shorter than the third; the anal fin has nine to thirteen (usually eleven) rays. Coloration is olive-green on the dorsum, with the sides silver and undersides white.

Striped bass spawn in midwater with strong currents in larger rivers, and although they are successfully adapted to freshwater habitat, they naturally spend most of their adult lives in saltwater. In Arkansas, M. saxatilis typically spawns semibouyant (suspended) eggs in certain watersheds (like the Arkansas River) with current in April. In reservoirs, however, the eggs tend to sink to the bottom and eventually die from siltation and other negative factors.

Concerning sport fishing, striped bass are of significant value and have been introduced into many waters outside their natural range for this sport and commercial fisheries. They feed primarily on other fishes, including shad with minor quantities of crayfish, mayflies, and other invertebrates. Anglers use a variety of fishing methods to catch this fish, including deepwater lure trolling and surf casting with topwater lures, as well as bait casting with live and dead bait (minnows or shad). The largest striped bass ever taken by angling was a 37.1 kg (81.9 lb.) specimen taken off the coast of Westbrook, Connecticut. A 32.0 kg (70.6 lb.) landlocked striper was caught in 2013 on the Warrior River in Alabama, setting a world record. An Arkansas rod and reel record was set by M. saxatilis, a 29.3 kg (64 lb., 8 oz.) specimen from Beaver Lake tailwater.

Striped bass have also been hybridized in Arkansas Game and Fish Commission hatcheries with M. chrysops to produce hybrid striped bass (M. chrysops × M. saxatilis) for dispersal in the state. These hybrids have been stocked in many freshwater areas across North America, including DeGray Lake, Arkansas, in 1975, followed by twelve other impoundments in the state. The lateral stripes on these bass are distinct but usually broken, several extending to the caudal fin. Hybrids also have two tooth patches near the midline toward the back of the tongue, and they may be distinct or close together. When it comes to distinguishing M. saxatilis from M. chrysops × M. saxatilis hybrids, the latter has a deeper body and broken lateral stripes. The Arkansas rod and reel record for a hybrid (M. chrysops × M. saxatilis) was set by a 12.4 kg (27 lb., 5 oz.) fish from Greers Ferry Lake.

White Perch

The white perch (Morone americana) is not a true perch, but rather a moronid fish notable as a food and game species in eastern North America. Although found most often in brackish waters, it also occurs in freshwater coastal drainages and estuaries of the Atlantic Coast drainages of North America from the St. Lawrence drainage of Quebec south to the Pee Dee River of South Carolina. They have also been introduced widely as far west as Colorado. They are found occasionally in small landlocked lakes and ponds but prefer brackish and freshwater pools and other quiet water areas of medium and large rivers, usually over a muddy substrate.

Historically, white perch were collected in 1993 from the Mississippi River (in Missouri) about 160 km (37.3 mi.) north of the Arkansas state line. Whether those Missouri specimens gained access to the Mississippi River from one of the Great Lakes or from the Missouri River system proper is unknown. There are very few records of M. americana in the Arkansas. Three adult white perch were collected in 2006 with gill nets from the Arkansas River (Dardanelle Reservoir) below Ozark Lock and Dam in Franklin County. Another specimen was taken, also in 2006, with rotenone (C23H22O6) from Dardanelle Reservoir (Cabin Creek arm) in Johnson County. These four specimens are probably the result of downstream movement from populations established in Oklahoma since 2000. It is likely that M. americana will eventually establish breeding populations in the Arkansas River of Arkansas, and, if so, its possible effects on native fish populations are uncertain.

White perch are generally silvery-white in color, and, depending upon habitat and maturity, as they mature, specimens begin to develop a darker shade near the dorsal fin and along the top of the body. There are no dark stripes along the side of adults. There are nine to ten anal rays and no teeth on the tongue. White perch have been reported up to 49.5 cm (19.5 in.) in length and weighing 2.2 kg (4.9 lbs.).

As far as food habits, white perch have been reported to feed on the eggs of many fish species native to the Great Lakes, such as walleye and other true percid fishes. Indeed, at various times, fish eggs have been noted to comprise 100% of their diet. They also prefer to eat small minnows as well as bloodworms, grass shrimp, and razor clams.

Reproductively speaking, white perch are very prolific. They typically ascend large rivers from April to June to spawn. Females are capable of depositing over 150,000 eggs in a week-long spawning session. Several males will often attend a spawning female, and each may fertilize a portion of her eggs. The young hatch within one to six days of fertilization.

All four U.S. moronid species and the hybrid have been commonly reported to harbor various parasites. However, to date, little is known about their parasites in Arkansas waters.

For additional information:

Buchanan, Thomas M., Robert L. Limbird, and Frank J. Leone. “First Arkansas Records for White Perch, Morone americana (Gmelin), (Teleostei: Moronidae).” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 61 (2007): 123‒124. Online at http://scholarworks.uark.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1481&context=jaas (accessed on January 17, 2019).

Burgess, G. H. “Morone americana (Gmelin) White Perch.” In Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes, edited by D. S. Lee. Raleigh: North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, 1980.

———. “Morone chrysops (Rafinesque) White Bass.” In Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes, edited by D. S. Lee. Raleigh: North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, 1980.

———. “Morone mississippiensis Jordan and Eigenmann Yellow Bass.” In Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes, edited by D. S. Lee. Raleigh: North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, 1980.

———. “Morone saxatilis (Walbaum) Striped Bass.” In Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes, edited by D. S. Lee. Raleigh: North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, 1980.

Bonn, E. W. “The Food and Growth of Young White Bass (Morone chrysops) in Lake Texoma.” Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 82 (1952): 213–221.

Cloutman, Donald G. “Epistylis of White Bass and Striped Bass.” Fish Health Section of the American Fisheries Society Newsletter 3 (1975): 6.

Crawford, Tommy, Mike Freeze, R. Foort, Scott Henderson, G. O’Bryan, and D. Phillip. “Suspected Natural Hybridization of Striped Bass and White Bass in Two Arkansas Reservoirs.” Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference of Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies 1984, 455‒469.

Eckmayer, W. J., and F. J. Margraf. “The Influence of Diet, Consumption, and Lipid Use on Recruitment of White Bass.” Lakes and Reservoirs: Research and Management 9 (2004): 133–141.

Filipek, Steve, and L. Claybrook. “Stripers and Hybrids—What Do They Really Eat?” Arkansas Game and Fish 15 (1984): 8‒9.

Hartman, K. J. “Population-Level Consumption by Atlantic Coastal Striped Bass and the Influence of Population Recovery Upon Prey Communities.” Fisheries Management and Ecology 10 (2003): 281.

Helfman, Gene, Bruce B. Collette, Douglas E. Facey, and Brian W. Bowen. The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

Hergenrader, G. L. “Current Distribution and Potential Dispersal of White Perch (Morone americana) in Nebraska and Adjacent Waters.” American Midland Naturalist 103 (1980): 404‒407.

Hergenrader, G. L., and O. P. Bliss. “The White Perch.” Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 100 (1971): 734–738.

Hoffman, Glenn L. Parasites of North American Freshwater Fishes. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Kilambi, Raj V., and Alex Zdinak, Jr. “The Biology of Striped Bass, Morone saxatilis, in Beaver Reservoir, Arkansas.” Proceedings of the Arkansas Academy of Science 35 (1981): 43‒45, 1981. Online at http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol35/iss1/12/ (accessed January 17, 2019).

Matthews, William J., Loren G. Hill, David R. Edds, and Francis P. Gelwick. “Influence of Water Quality and Season on Habitat Use by Striped Bass in Large Southwestern Reservoir.” Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 118 (1989): 243‒250.

Matthews, William J., Loren G. Hill, Jan J. Hoover, and T. G. Heger. “Trophic Ecology of Striped Bass, Morone saxatilis, in a Freshwater Reservoir Lake (Lake Texoma, U.S.A.).” Journal of Fisheries Biology 33 (1988): 273‒288.

Newton, S. H., and Raj V. Kilambi. “Fecundity of White Bass, Morone chrysops (Rafinesque), in Beaver Reservoir, Arkansas.” Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 102 (1973): 446‒448.

Olmsted, Larry, and Raj V. Kilambi. “Stomach Content Analysis of White Bass (Roccus chrysops) in Beaver Reservoir, Arkansas.” 23rd Annual Conference of the Southeastern Association of Game and Fish Commission (1969): 244-–250.

Page, Larry M., and Brooks M. Burr. Peterson Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America North of Mexico. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011.

Pflieger, William L. The Fishes of Missouri. Jefferson City: Missouri Department of Conservation, 1997.

Robison, Henry W., and Thomas M. Buchanan. Fishes of Arkansas. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Williams, H. P. “Characteristics for Distinguishing White Bass, Striped Bass and Their Hybrid (Striped Bass x White Bass).” Proceedings of the Southeastern Association of Game and Fish Commission 29 (1976): 168‒172.

Yellayi, R. R., and Raj V. Kilambi. “Population Dynamics of White Bass in Beaver Reservoir, Arkansas.” Proceedings of the Southeastern Association of Game and Fish Commission 29 (1976): 172‒184.

Chris T. McAllister

Eastern Oklahoma State College

Science and Technology

Science and Technology Moronids

Moronids

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.