calsfoundation@cals.org

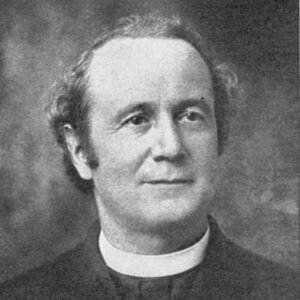

Pietro Bandini (1852–1917)

Father Pietro Bandini, a Roman Catholic priest, is most widely remembered in Arkansas for the 1898 founding of Tontitown (Washington County), located in the northwestern corner of the state, which he named after Henry de Tonti, an Italian explorer who established, with René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, the first European settlement in Arkansas in 1686. However, the founding of Tontitown is but a regional capstone on a life spent working for the betterment of Italian immigrant communities in the nation.

Bandini was born on March 31, 1852, in Forli, which is in the Romagna region of Italy. Little is known about Bandini’s family, described as of the upper class and refined. He is known to have had two older brothers, one of whom was also a priest in the Society of Jesus. Bandini spent 1869 through 1871 at the Jesuit novitiate in the principality of Monaco, after which he began the first of three years of study of philosophy there. In September 1874, he began his first year of regency, or teaching and perfecting, at the Jesuit seminary at Aix en Provence in Lyons, France, where he studied theology. He was ordained a priest on September 30, 1877, at Bertinoro, south of Forli in the Romagna. His first assignment was at St. Vincenzo de’ Paoli, where he served as chaplain to the Brothers of Oratory of Our Lady Mother of Mercy and where he later established a school for boys and girls dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

Father Bandini was sent to the Jesuits’ Rocky Mountain Mission in Montana Territory in 1882 as a Jesuit Missionary to the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary Church in Helena, Montana. There, he studied both English and Indian languages. A year later, he was stationed at St. Ignatius Mission, Montana, where he built a church and school and traveled into Indian Villages instructing both Crow and Kootenai Indians in the Catholic faith. He later successfully started a mission for Cheyenne Indians. Bandini returned to Europe in March 1889, where he was appointed vice-rector of St. Thomas Aquinas College in Cuneo, Italy. He remained in this position for one year, after which he returned to the United States and established St. Raphael’s Italian Benevolent Society, the purpose of which was to assist Italian immigrants at the Port of New York.

Bandini wrote his superior, Archbishop Corrigan, “I guess it is my right and duty to go among them, and I beg Your Grace to appoint me for the temporal and spiritual relieve [sic] of my people.” Bandini was an efficient and effective worker in sustaining the Italian mission in New York. He assisted over 20,000 of his countrymen entering America, finding housing and employment for them. Bandini continued his work in New York for five years before the opportunity to explore his life-long dream of founding a colony for Italian immigrants presented itself.

In December 1896, Bandini took the first step toward proving his theory that, by placing Italian immigrants in the interior of the United States, on land similar to that of their homeland, they could prosper and become useful citizens. With the approval of his superior, a man named Satolli, he requested that he be assigned as chaplain for a colony of Italian immigrants being enlisted by Austin Corbin, a wealthy New York industrialist, to work the land on his Sunnyside Plantation in Chicot County.

The first group of Italians came to the United States aboard the Chateau Vquen and docked at the port of New Orleans on November, 26, 1895, arriving at Sunnyside later that month. Bandini himself arrived in Sunnyside in January 1897 with a second group of Italian immigrants traveling by railway from New York. Upon arriving in Sunnyside, Father Bandini was faced with overwhelming problems. Over 125 people of the original 100 Italian families died of malaria—contaminated water, poor sanitation, mosquitoes, and the climate contributed to disease.

Austin Corbin lost his life in a buggy accident in June 1896; the new owners, uninterested in the welfare of the Italian immigrants, failed to improve the unhealthy conditions. A few families with enough money returned to Italy. Poverty forced the rest to remain, and they turned to Bandini for survival. He realized that Sunnyside in the Arkansas Delta was not the place for his people. This opportunity to test his theory of placing Italian immigrants in an environment similar to that of their homeland could only improve the lives of his countrymen.

Bandini had previously traveled through the Ozark Plateau, where he found land rather like the homeland of these immigrants, with 1,500-foot elevations, a healthful climate, and passable soil. In January 1898, Bandini returned to northwestern Arkansas and found 800 acres of farmland for sale. Before he could purchase the land, forty families from Sunnyside arrived, and the owner increased the asking price of eight dollars an acre to fifteen dollars an acre. Father Bandini complied; thus was Tontitown founded.

During their first winter, the settlers lived in deserted farm buildings, surviving on rabbit, pasta, and polenta, a hearty dish made with cornmeal and water. Father Bandini put an abandoned schoolhouse to use as a school and place for church services. He divided the land into parcels of ten acres, and a random drawing provided a fair distribution of the land.

In the spring, the immigrants planted vegetable gardens, and family vineyards providing them with vegetables and grapes for wine and jelly. Under the leadership of Father Bandini, these vineyards were expanded into a commercial venture. Tontitown’s grape industry changed the face of northwestern Arkansas.

Tontitown prospered and, by 1905, was known as the perfect example of colonization. That same year, the Italian ambassador of Washington DC, Baron E. Mayor des Planches, came for a visit. Surprised by the beauty and prosperity of Tontitown, he asked, “What has done it?” “It’s Father Bandini here and his people,” a local citizen replied.

Bandini prepared a pamphlet titled “Tontitown, Arkansas, the World’s Ideal Vineyard” for the Kansas City and Memphis Railway Company, which distributed it throughout the country, bringing more Italian families to settle in Tontitown.

In 1911, Bandini returned to Italy. Pope Pius X and the Queen Mother Margherita, widow of King Umberto, king of Sardinia and the first king of Italy, pledged to work to change the way immigration was conducted, promising to adopt Father Bandini’s methods of colonization. Bandini received a medal from the Italian government, a gold chalice and a set of red vestments from the pope, along with a second set of white vestments from the Queen Mother Margherita.

Father Bandini died on January 2, 1917, at St. Vincent Infirmary in Little Rock (Pulaski County) of heart failure. He is interred in St. Joseph Cemetery in Tontitown.

For additional information:

“Father Bandini Dies in Hospital.” Springdale News, January 5, 1915, p. 1.

Lemke, W. J., ed. “The Story of Tontitown.” Washington County Historical Society Bulletin 44 (1963).

Lewellen, Jeffrey. “Sheep Amidst the Wolves: Father Bandini and the Colony at Tontitown.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 45 (Spring 1986): 19–40.

Rothrock, Thomas. “The Story of Tontitown, Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 16 (Spring 1957): 84–88.

Mary Vaughan

Tontitown Historical Museum

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Religion

Religion Bandini Memorial

Bandini Memorial  Pietro Bandini Funeral

Pietro Bandini Funeral  Pietro Bandini

Pietro Bandini  Pietro Bandini

Pietro Bandini

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.