calsfoundation@cals.org

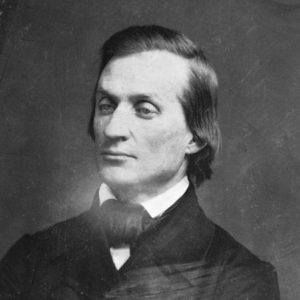

Solon Borland (1811–1864)

Solon Borland was a physician, editor, United States senator, diplomat, and military officer. He was the first Arkansas politician to be given a major diplomatic assignment, which eventually resulted in the destruction of a town in Central America, one of the earliest examples of U.S. gunboat diplomacy.

According to an article in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Solon Borland was born in Suffolk, Nansemond County, Virginia, the youngest of three sons born to Thomas Wood Borland, a physician, and Harriet Godwin.

Additional sources have his date of birth as August 8, 1811. His family moved to North Carolina by 1823. In 1831, he married Hildah (or Huldah) Wright of Virginia; they had two sons, Harold and Thomas. He attended the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in Philadelphia in 1833–1834, where he earned credentials to practice medicine. By late 1836, he had moved to Memphis, Tennessee, to practice medicine, and his first wife died there on August 25, 1837. His children went to live with relatives in Mississippi and Virginia. On July 23, 1839, he married Eliza Buck Hart of Memphis. She died in 1842, with no offspring. During this time, Borland earned an additional medical degree on March 2, 1841, from a medical school in Louisville, Kentucky.

Borland eventually preferred politics over medicine, founding a Democratic newspaper, the Western World and the Memphis Banner of the Constitution, in January 1839. In 1843, the Arkansas Democratic Party hired him to edit its newly created newspaper, the Arkansas Banner, which first appeared in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in September 1843, with Borland assuming his duties in November. Borland quickly displayed a violent temper when he physically assaulted Benjamin J. Borden, the editor of the rival Whig paper, the Arkansas Gazette, in January 1844; the two eventually reconciled a few years later.

Borland was wed a third and final time on May 28, 1845, to Mary Isabel Melbourne of Little Rock, and the couple had three children. Their only son, George Godwin Borland, died during the Civil War. Two daughters, Fanny Green Borland and Mary Melbourne Borland, were still living by the time of their father’s death. Borland volunteered for service at the outbreak of the Mexican War, a conflict he had strongly supported as editor. Captured on January 23, 1847, just south of Saltillo, Mexico, Borland managed to escape to participate in the final attack on Mexico City in September 1847. Borland returned to Little Rock by December 1.

Back in Arkansas, the military veteran received a political boost when Ambrose Sevier resigned his seat in the U.S. Senate in March 1848 to become a peace commissioner implementing the peace treaty with Mexico. Governor Thomas S. Drew appointed Borland to the vacant seat on March 30, 1848, and he was to hold it until Sevier could reclaim it later that year. During his tenure, Borland initiated congressional action on a district judge for the Western District of Arkansas, swampland reclamation, and back pay for American prisoners from the Mexican War. In November 1848, he successfully blocked Sevier’s return to the Senate by winning election to a full Senate term by just four votes in the Arkansas legislature.

Borland had a colorful career in the U.S. Senate. During the Compromise Crisis of 1850, he vociferously defended “Southern rights” and physically assaulted Senator Henry Foote of Mississippi. Back home in the summer of 1850, Borland quickly discovered that his disunionist views were not popular. Borland gave a speech in Little Rock during July attacking abolitionism and admitting that he had problems with the proposed sectional compromise, but he never returned to the Senate to vote on the final proposal, which was passed by September. Borland’s absence was widely interpreted as his acquiescence to the Compromise of 1850.

Always an expansionist, the Arkansas senator revealed in 1853 his reasons for voting against the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty of 1850, a treaty with Britain that prevented either nation from claiming exclusive rights to build a canal in Central America. Borland claimed in May 1850 that this treaty violated the Monroe Doctrine and stymied American growth. Apparently, such views appealed to the incoming administration of Franklin Pierce, which appointed him minister plenipotentiary to Central America and stationed him in Nicaragua.

Borland arrived in Managua in September 1853 and immediately started trouble. As minister, he called for the United States to repudiate the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty and for the American military to support Honduras in its confrontation with Britain. In mid-October, in a public address in Nicaragua, he announced that it was his greatest ambition to see Nicaragua “forming a bright star in the flag of the United States.” This speech, and Borland’s incessant demands, caused Secretary of State William Marcy to reprimand him, which subsequently caused the prickly Arkansan to resign. As Borland was leaving in May 1854, he interfered with the arrest of an American citizen in the coastal town of San Juan del Norte. Borland was threatened with arrest but was not arrested due to his diplomatic immunity. While he was arguing with local officials, someone threw a bottle in his face. The enraged diplomat reported this incident to the Pierce administration, which dispatched an American naval ship to the area to demand an apology. When none was forthcoming, the American ship and marines bombarded and burned San Juan del Norte, an early example of gunboat diplomacy.

Borland returned to Little Rock by October 1854 to resume a medical practice and operate a drugstore. However, he could not stay away from the editor’s chair, and by the summer of 1855, he was accompanying Christopher C. Danley as editor of the Arkansas Gazette, in which he had bought a half-interest in 1853. By August 1855, the Gazette had become the official mouthpiece of the American Party (popularly dubbed the Know-Nothing Party). This party opposed unrestricted foreign immigration, and since many of the immigrants were Irish Catholics, it sought also to restrict the voting rights of this religious minority. The American Party failed at the polls in the state elections in the summer of 1856. Borland left Little Rock by the fall to resume a medical practice in Memphis and to edit a newspaper. He also maintained a residence in Princeton (Dallas County) where his wife and children lived.

Borland was in Arkansas in 1860 campaigning that September for John Bell and the Constitutional Union ticket. He also pursued a seat in the Tennessee legislature in early 1861, but was defeated. He then sold his Memphis newspaper and returned to Arkansas. After the firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861, Governor Henry Massie Rector appointed Borland commander of a volunteer militia and ordered him to capture the Federal arsenal in Fort Smith (Sebastian County), even though Arkansas had not yet formally seceded. By the time Borland made it to Fort Smith, the Federal forces had already departed. The militia returned to Little Rock and disbanded. Many of them were placed by the Arkansas Secession Convention into the Capital Guards. That fall Borland won a position as Confederate commander for northeastern Arkansas. As a Confederate officer, he ordered an embargo of goods to end price speculation, but Governor Rector rescinded his order. Borland protested that a governor could not countermand a Confederate official, but in January 1862, Borland’s directive was countermanded by Confederate secretary of war Judah P. Benjamin. After this embarrassment, Borland retired from the Confederate service.

By June 1862, Borland had resumed his medical practice in Little Rock. His third wife died there in October 1862. Before Little Rock fell to Union forces on September 10, 1863, Borland apparently moved to Princeton in southwestern Arkansas. He left for Texas on September 13, 1863, and wrote his will on December 31, 1863, dying in Harris County the next day; his exact place of burial, however, is unknown, but there was placed a marker for him in Mount Holly Cemetery in 1992.

For additional information:

Dougan, Michael B. Confederate Arkansas: The People and Policies of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.

“Notes and Queries: The Borlands and Godwins.” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 17 (1909): 97–98.

Ross, Margaret. The Arkansas Gazette: The Early Years, 1819–1866. Little Rock: Arkansas Gazette Foundation, 1969.

Teske, Steven. Unvarnished Arkansas: The Naked Truth about Nine Famous Arkansans. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2012.

Woods, James M. “Expansionism as Diplomacy: The Career of Solon Borland in Central America, 1853–1854.” The Americas: A Quarterly Review of Inter-American Cultural History 40 (January 1984): 399–415

———. Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas’s Road to Secession. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

James M. Woods

Georgia Southern University

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Military

Military Politics and Government

Politics and Government Solon Borland

Solon Borland  Solon Borland

Solon Borland

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.