calsfoundation@cals.org

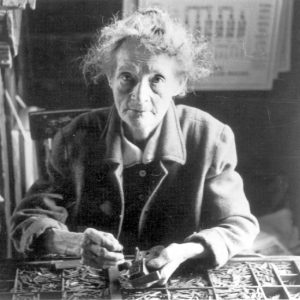

Virginia Maud Dunlap Duncan (1873–1958)

Virginia Maud Dunlap Duncan was the second woman in Arkansas to secure a registration as a pharmacist. As a young businesswoman and editor of a newspaper, she ran for mayor of Winslow (Washington County) with an all-woman slate for city council. This “petticoat government” was elected to two consecutive terms and gained national attention during its time in office.

Maud Dunlap was born on October 22, 1873, in Fayetteville (Washington County) to Dudley Clinton and Catherine Hewitt Dunlap. Her mother died when Dunlap was an infant. She and her brother, Rufus, went to live with her uncle Albert Dunlap and his wife, Virginia, in Fort Smith (Sebastian County). Other foster parents raised Dunlap’s sister and other two brothers.

Dunlap’s foster father educated her at home until she enrolled in high school in Fort Smith. At the age of sixteen, she received a teacher’s certificate from Cane Hill College. She taught briefly at one-room schools in the area and played organ at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, which was founded by her foster parents.

On February 26, 1894, Dunlap married Hallam Pearce of Milan, Tennessee, a worker for the Frisco Railroad in Winslow. The couple had two daughters. One died in infancy, and the other died shortly after the marriage was annulled on October 3, 1901. Pearce secured her registration as a pharmacist in 1906, after which she worked in the M. D. Pearce (Maud Dunlap Pearce) drug store in Winslow with her foster father, whom in interviews she referred to as simply her father. Pearce legally reverted to her maiden name of Dunlap in 1907.

She married a young newspaperman, Gilbert Nelson Duncan, on June 3, 1908. The couple had no children. While Duncan continued to practice as a pharmacist, she and her husband purchased a monthly newspaper, the Winslow Mirror. They changed its name to the Winslow American and, on September 4, 1908, began weekly publication from an upstairs room over the drug store. Maud Duncan’s editorials commented on national questions, and she was most interested in women’s suffrage issues. Through the newspaper, the couple supported the United States’ participation in World War I and actively helped sell war bonds.

After her husband died in the flu epidemic of 1918, Duncan continued to operate the drug store and the newspaper. Duncan’s interest in civic matters and women’s rights, and a firm belief, evidenced by her writings in the Winslow American, that women could do as good a job running a city as men, convinced her to run for mayor. She was elected with a full slate of women candidates as her city council. During the 1925–26 term, her “petticoat government” raised money to build a much-needed road up the steep mountainside to the west. The city council encouraged residents of the town to spruce up their homes and plant flowers, suggesting that merchants offer low prices on building materials for the betterment of the community.

As mayor, Duncan gave away the small jail, stating that those who broke the law would appear before her and pay a fine and that worse criminals could be dealt with by lawmen of the county. After being reelected for a second one-year term and serving successfully, the women declined to run again in 1927. During its two years in office, Winslow’s “petticoat government” attracted attention in many national newspapers.

After the pharmacy burned in 1935, the newspaper office moved to a cold, drafty building on Highway 71 to the southeast. Duncan continued to set type by hand and sell ads to keep the failing business going. By that point, the newspaper had gone from a vital four-page weekly to a sporadically issued single sheet. Duncan continued to write editorials and cover local events until 1956, when she became so frail that friends and neighbors took her to a retirement home in Fayetteville.

Duncan was nationally recognized many times, not only for her unusual service as mayor and as a prominent woman pharmacist but for continuing to write and publish the Winslow American under the most difficult of circumstances. The original Winslow American building was moved to its present location, about one mile north of Winslow on Highway 71, in 1960. For a short period of time, the building housed a small museum that contained printing equipment, including an old foot-treadle press and her pharmaceutical equipment. The building was later converted into a residence, and Harvey Jones bought the press, which is now housed in Har-ber Village Museum in Grove, Oklahoma.

Duncan died in Fayetteville on January 21, 1958, at the age of eighty-five. She is buried at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Cemetery in Winslow.

For additional information:

Williams, Nancy A., ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Winn, Robert. The Story of Winslow’s Maud Duncan. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1992.

Winn, Robert, and Lyda Winn Pace. Winslow: Top of the Ozarks. Fayetteville, AR: Robert Winn, 1983

Velda Brotherton

Winslow, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Health and Medicine

Health and Medicine Mass Media

Mass Media Politics and Government

Politics and Government Maud Duncan

Maud Duncan  Maud Duncan

Maud Duncan  Maud Duncan Museum

Maud Duncan Museum  Maud Duncan Display

Maud Duncan Display

Maud Dunlap (or Aunt Maudie as we call her) was my grandmother Catherine Dunlap’s sister. I am grateful to find this article about her.