calsfoundation@cals.org

Lee Elhardt Hays (1914–1981)

Lee Elhardt Hays was a singer best known as the big man who sang bass with the folk music group the Weavers. According to historian Studs Terkel, the Weavers were responsible for “entering folk music into the mainstream of American life.” Among the songs he is most known for are: “If I Had a Hammer,” “Roll the Union On,” “Raggedy, Raggedy, Are We,” “The Rankin Tree,” “On Top of Old Smoky,” “Kisses Sweeter than Wine,” and “Goodnight Irene.”

Lee Hays was born on March 14, 1914, in Little Rock (Pulaski County) to a strict Methodist preacher, William Benjamin Hays, and Ellen Reinhardt Hays. Hays’s father was serving as editor of the Arkansas Methodist at this time but later went back to the pulpit. By the time Hays was twelve, he had lived in five different Arkansas towns: Little Rock, Newport (Jackson County), Paragould (Greene County), Conway (Faulkner County), and Booneville (Logan County). He started school in Arkansas and finished high school in Georgia as his father traveled the Methodist circuit.

Hays spent much of his life rebelling against his father’s fundamentalism; he took up smoking and drinking at an early age and never gave them up. However, his church background provided a deep-seated religious element to his singing and songwriting. Some said Hays’s political principles had a fundamentalist quality of their own.

Hays became a student at Commonwealth College in the late 1930s as America was deep into the Great Depression. This rural college located near Mena (Polk County) had dedicated itself to helping working men by promoting the organization of labor unions. Hays was appalled at the hardships endured by southern sharecroppers and laborers and thought that union activism was essential to American workers.

At Commonwealth, Hays dressed in overalls, attended labor-oriented classes, and worked with other students in the fields. New York playwright Eli Jaffe, a fellow student, recalled that Hays was “deeply religious and extremely creative and imaginative and firmly believed in the Brotherhood of Man.” Hays also preached in area churches and wrote songs, plays, and stories.

Hays transformed hymns and black spirituals into songs about unions, sometimes substituting the word “union” for “Jesus.” His labor-related ballads pleased his contemporaries so much that they raised sixty-five dollars to send him to New York City to gain a larger audience. In New York, Hays met Pete Seeger, another young political singer who became Hays’s lifelong friend and collaborator. They dreamed of using folk music, the traditional music of the poor, to achieve political goals.

Hays and Seeger began singing with small local groups that included famous musicians such as Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Burl Ives, and Josh White. In 1940, Seeger created the Almanac Singers, who lived in a commune and coined the word “hootenanny.”

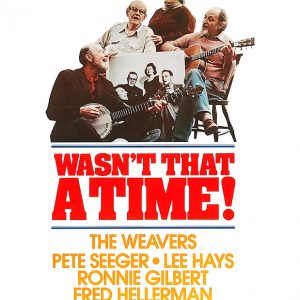

The group broke up during World War II because Seeger enlisted in the army. After the war, Seeger and Hays tried to revive the group but failed. In 1948, in Seeger’s Greenwich Village basement, Ronnie Gilbert, Fred Hellerman, and Hays joined Seeger in creating the Weavers, who, in the 1950s, brought folk music to a mass audience for the first time. The group took its name from a nineteenth-century play of the same name written by German playwright Gerhard Hauptmann that dealt with a strike among textile workers. Recording for Decca Records (and later for Vanguard), the group was highly successful with “Goodnight Irene,” “On Top of Old Smoky,” “So Long, It’s Been Good to Know Ya,” and “Kisses Sweeter than Wine.” Seeger and Hays composed “If I Had a Hammer” while nonchalantly passing a notepad between them at a political meeting. Both considered themselves “political performers.”

Unfortunately, the Weavers’ success came during the McCarthy era. The Weavers were blacklisted and put under surveillance because of some members’ political beliefs. They were barred from television, engagements were canceled, and radio stations refused to play their music. They disbanded in 1952 but reunited in 1955 after a staged Carnegie Hall reunion of the band sold out. In the audience of this December 24, 1955, show were people who later created the Limelighters; the Kingston Trio; Peter, Paul and Mary; and Mitch Miller. In fact, Mary Travers of Peter, Paul and Mary later credited the Weavers with the success and the very existence of her own folk group.

Among the albums the Weavers cut were Wasn’t That a Time, Union Songs, Talking Union, Sod Buster Ballads, Deep Sea Chanteys, Gospel, Best of the Weavers, Goodnight Irene, Kisses Sweeter Than Wine, and Together Again.

Hays was plagued by ill health, and the Weavers’ farewell concert came in December 1963 at the Orchestra Hall in Chicago, Illinois. Hays lost both legs, which were amputated due to his diabetes, and his health continued to deteriorate.

In November 1980, a final concert was held at Carnegie Hall. Although Hays was almost unrecognizable in his wheelchair, the Weavers’ music filled the hall. Nine months later, on August 26, 1981, Hays died from diabetic cardiovascular disease at his home in Croton-on-Hudson, New York. His body was cremated, and his friends met to mix the ashes with his compost pile.

For additional information:

Coogan, Harold. “The Ballad of Lee Hays.” Arkansas Times (July 1988): 40–44.

Jarnow, Jesse. Wasn’t That the Time: The Weavers, the Blacklist, and the Battle for the Soul of America. New York: Da Capo Press, 2018.

Koppelman, Robert. “Lee Hays: A Literary Reconsideration.” Southern Folklore 55, no. 2 (1998): 75–100.

Sharlet, Jeff. “The Embattled Lee Hays.” Oxford American no. 58 (Fall 2007). https://oxfordamerican.org/magazine/issue-58-fall-2007/the-embattled-lee-hays (accessed March 11, 2025).

Stambler, Irwin, and Grelun Landon, eds. The Encyclopedia of Folk, Country and Western Music. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983.

The Weavers: Wasn’t That a Time! Warner Bros., 1982.

Withey, Beth. “‘Some Kind of Socialist:’ Lee Hays, the Social Gospel, and the Path to the Cultural Front.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2020. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3932/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Willens, Doris. The Lonesome Traveler: A Biography of Lee Hays. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1988.

Harold Coogan

Mena, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.