calsfoundation@cals.org

Louis Thomas Jordan (1908–1975)

Louis Thomas Jordan—vocalist, bandleader, and saxophonist—ruled the charts, stage, screen, and airwaves of the 1940s and profoundly influenced the creators of rhythm and blues (R&B), rock and roll, and post–World War II blues.

Louis Jordan was born on July 8, 1908, in Brinkley (Monroe County). His father, Dardanelle (Yell County) native James Aaron Jordan, led the Brinkley Brass Band; his mother, Mississippi native Adell, died when Louis was young. Jordan studied music under his father and showed promise in horn playing, especially clarinet and saxophone. Due to World War I vacancies, young Jordan joined his father’s band himself. Soon, he was good enough to join his father in a professional traveling show—touring Arkansas, Tennessee, and Missouri by train, instead of doing farm work when school closed. Show venues included churches, lodges, parades, picnics, or weddings; bands had to be ready to handle Charlestons, ballads, and any requests.

Jordan briefly attended Arkansas Baptist College in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in the late 1920s—he was later a benefactor to the school—and performed with Jimmy Pryor’s Imperial Serenaders in Little Rock. He played saxophone and clarinet with the Imperial Serenaders and Bob Alexander’s Harmony Kings in El Dorado (Union County) and Smackover (Union County) during their boom lumber and oil eras, getting twice the going five-dollars-per-gig rate in Little Rock. The Harmony Kings then took a job at Wilson’s Tell-’Em-’Bout-Me Cafe in Hot Springs (Garland County); Jordan also performed at the Eastman Hotel and Woodmen of the Union Hall and with the band of Ruby “Junie Bug” Williams at the Green Gables Club on the Malvern Highway near town, as well as at the Club Belvedere on the Little Rock Highway. He rented a room at Pleasant and Garden streets in Hot Springs.

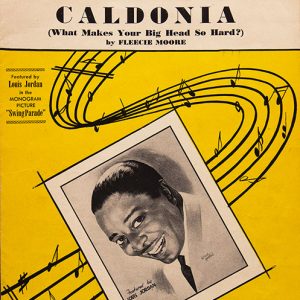

The lengths and legitimacy of his marriages are in some dispute. He first married Arkadelphia (Clark County) native Julia/Julie (surname unknown). He met Texas native singer and dancer Ida Fields at a Hot Springs cakewalk and married her in 1932, though he may have still been married to his first wife. He and Fields divorced in the early 1940s when he took up with childhood sweetheart Fleecie Moore of Brasfield (Prairie County), a dozen miles from Brinkley. They married in 1942. Moore is listed as co-composer on many hit Jordan songs, such as “Buzz Me,” “Caldonia Boogie,” and “Let the Good Times Roll.” Jordan used her name to enable him to work with an additional music publisher; he had cause to regret it later, however, after she stabbed him during an argument, and though they reconciled for a time, he ended up divorcing her. Jordan married dancer Vicky Hayes in 1951 (and separated from her in 1960) and singer and dancer Martha Weaver in 1966.

In the 1930s, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Jordan found work in the Charlie Gaines band—playing clarinet, and soprano and alto sax, in addition to doing vocals—which recorded and toured with Louis Armstrong. The two Louises would later play duets when Jordan became a solo star. Jordan learned baritone sax during this period. In 1936, he joined nationally popular drummer Chick Webb’s Savoy Ballroom Band. Ella Fitzgerald was the band’s featured singer; Jordan played sax and got the occasional vocal, such as “Rusty Hinge,” recorded in March 1937. In 1938, Jordan was fired by Webb for trying to convince Fitzgerald and others to join his new band.

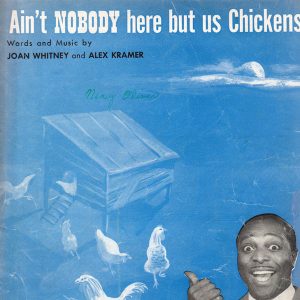

Jordan’s band, which changed American popular music, was always called the Tympany Five, regardless of the number of pieces. The small size of Jordan’s Tympany Five made it innovative structurally and musically in the Big Band era. Among the first to join electric guitar and bass with horns, Jordan set the framework for decades of future R&B and rock combos. Endless rehearsals, matching suits, dance moves, and routines built around songs made the band; Jordan’s singular brand of sophisticated yet down-home jump blues and vocals made it a success. His humorous, over-the-beat monologues and depictions of black life are a prototype of rap; his crossover appeal to whites calcified his popularity. Jordan charted dozens of hits from the early 1940s to the early 1950s—up-tempo songs like “Choo Choo Ch’Boogie” (number one for eighteen weeks) and “Ain’t Nobody Here But Us Chickens” (number one for seventeen weeks), and ballads like “Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t (My Baby).”

With Jordan’s clowning for crowds, often overlooked was his musical talent. He could play a solo and delve into a rapid-fire vocal or routine without missing a beat. He demanded no less from his groups, among the most polished of their peers. Although Jordan’s songs could depict drunken, raucous scenes—like “Saturday Night Fish Fry” (number one for twelve weeks) and “What’s the Use of Gettin’ Sober?”—he did not drink or smoke and could be quiet and aloof, in contrast to the jiving hipster he portrayed. Jordan was also a fine ballad singer—as songs such as “Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying” and “I’ll Never Be Free,” sung with Ella Fitzgerald, show. He helped introduce calypso music to America and toured the Caribbean in the early 1950s, fooling natives with his faux West Indian singing accent.

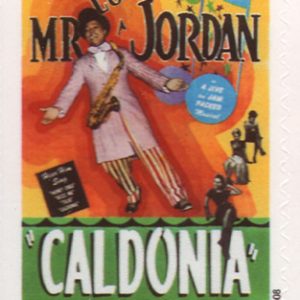

Jordan said he chose to play “for the people”—no be-bop or self-indulgent solos, just Jordan’s unique, fun urban blues. He also starred in early examples of music video—“Soundies,” introduced in 1940—and longer films based around his songs, such as Beware! (1946), Reet, Petite, and Gone (1947), and Look Out Sister (1948). He cameoed in movies like Follow the Boys (1944) and Swing Parade of 1946 (1946). Loved by World War II GIs, and selected to record wartime “V-discs,” he remains known overseas today.

The sounds Jordan pioneered conspired to slow his record sales as R&B and rock and roll emerged. His more than fifteen years on Decca—not counting his time there with Webb—ended in 1954; he sold millions of records for the company and performed duets with Armstrong, Bing Crosby, and Fitzgerald. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Jordan released consistently engaging material, but for a variety of labels (Aladdin, Black Lion, RCA’s X, Vik, and Ray Charles’s Tangerine) and to decreasing results. Jordan continued to tour, including Europe and Asia in the late 1960s. He returned to Brinkley in 1957 for Louis Jordan Day. He spent much of the late 1960s and early 1970s without a recording contract. In 1973, Jordan issued a final LP, I Believe in Music, on the Black & Blue label.

Just over a year later, on February 4, 1975, he died in Los Angeles, California. Jordan is buried in St. Louis, hometown of his widow, Martha.

A host of prominent musicians claim his influence, including Ray Charles, James Brown, Bo Diddley, and Chuck Berry. His songs have appeared in commercials, on TV, and in movies and have been recorded by dozens of popular artists. Tribute albums include Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown’s Sings Louis Jordan (1973), Joe Jackson’s Jumpin’ Jive (1981), and B. B. King’s Let the Good Times Roll (1999).

Jordan was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987 and named an American Music Master by the Hall in 1999. A musical revue of Jordan’s songs, Five Guys Named Moe, played on London’s West End and Broadway in the 1990s. A nine-CD Decca retrospective was released by Germany’s Bear Family in 1992. In Little Rock, the first Louis Jordan Tribute concert was held in 1997, with proceeds benefiting a Jordan bust in Brinkley by artist John Deering. Jordan was inducted into the Arkansas Entertainers Hall of Fame in 1998 and the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame in 2005. In 2008, the U.S. Postal Service released a stamp featuring Jordan as he appeared in the 1945 short film Caldonia. Act 810 of 2017 designated U.S. Highway 49 from Brinkley to Marvell (Phillips County) the Louis Jordan Memorial Highway. In 2018, Jordan was posthumously honored with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

For additional information:

Chilton, John. Let the Good Times Roll: The Story of Louis Jordan and His Music. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Feather, Leonard. The Encyclopedia of Jazz. New York: Horizon Press, 1955.

Jancik, Wayne, and Tad Lathrop. Cult Rockers. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Koch, Stephen. Louis Jordan: Son of Arkansas, Father of R&B. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2014.

Sampson, Henry T. Blacks in Black and White: A Source Book on Black Films. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1995.

Stephen Koch

Arkansongs

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

My favorite has to be the birthday boogie! He did have many more memorable hits!

I still play them often!

This is a great story of a great Arkansan, particularly if you’re from the same hometown as Mr. Jordan. I am glad to have that connection! I had the good fortune of seeing the production of Five Guys Named Moe and was never more proud that it was based on Mr. Jordan’s creativity. May we long speak his name.