calsfoundation@cals.org

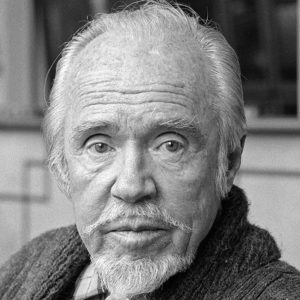

Samuel Conlon Nancarrow (1912–1997)

Samuel Conlon Nancarrow composed innovative music and produced a body of work largely for player piano. According to musicologist Kyle Gann, who has published a study of Nancarrow’s compositions, they are the most rhythmically complex ever written by anyone anywhere, featuring up to twelve different tempos at the same time. Gann describes “whirlwinds of notes…joyously physical in their energy.” The wealth of ideas in Nancarrow’s works has had a lasting impact on other composers.

Conlon Nancarrow was born in Texarkana (Miller County) on October 27, 1912. His father, Samuel Charles Nancarrow, was a businessman and mayor of Texarkana from 1927 to 1930. His mother was Myra Brady Nancarrow, and he had one brother, Charles.

At the insistence of his father, Nancarrow attended Western Military Academy in Alton, Illinois. While there, his interest in music blossomed, and he attended the National Music Camp in Interlochen, Michigan, the following summer. He began listening to jazz and composing. Nancarrow’s father sent him at age fifteen to Vanderbilt University to study engineering, but he stayed just one semester. Already proficient on the trumpet, he was still a teenager when he left Texarkana in 1929 to study at the Cincinnati College-Conservatory. He played jazz there in a German beer hall.

In 1932, he married Helen Rigby, a singer and contrabass player, in Cincinnati, Ohio. She divorced him in 1940. Later marriages were to Annette Margolis, a painter, from 1948 until their divorce in 1953, and Yoko Seguira, an anthropologist, in 1970, with whom he had a son, David Makoto, in 1971.

In 1934, Nancarrow moved to Boston, Massachusetts, where he studied composition privately with Walter Piston, Roger Sessions, and Nicolas Slonimsky and conducted a Works Progress Administration (WPA) orchestra.

Like many artists in that period, he joined the Communist Party in 1934 and went to Spain in 1937 with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade to fight against Francisco Franco’s fascist army. He was wounded and escaped in 1939 after Franco’s victory.

Upon his return to the United States in 1939, he discovered that Slonimsky had arranged for publication of two of his compositions. He settled in New York City, where he associated with other composers, including Aaron Copland and Elliott Carter.

Describing Nancarrow as an “undesirable” because of his Spanish experience, the State Department refused to issue him the passport he applied for after learning that his friends in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade were denied permission to travel. In protest, he moved to Mexico City in 1940, Mexico being the only country other than Canada where he could go without a passport. He lived there the rest of his life, becoming a Mexican citizen in 1956. His only return visit to Arkansas after moving to Mexico was in 1992, when he dealt with family matters.

As he continued composing, he realized that the complex rhythms he envisioned could be cut on a player piano roll. In 1947, he bought a player piano and punching machine and began composing his Studies for Player Piano, which captured the attention of the musical world. In 1960, Merce Cunningham choreographed several of Nancarrow’s compositions and presented them on a world tour in 1964. It was not until 1977, however, that scores of his Studies were published and recordings of all the Studies began.

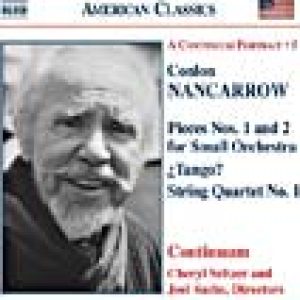

Beginning in 1981, Nancarrow made trips to the United States and Europe for performances of his music, and he received commissions from major artists. In 1982, he received a $300,000 MacArthur Fellowship “given in recognition of…major accomplishments in music which demonstrate…originality, dedication to creative pursuits, and capacity for self-direction.” In 1990, the New England Conservatory of Music awarded him an honorary doctorate, and the University of Mexico City presented two days of performances of his music, including his works for player piano. Significant works include approximately fifty Studies for Player Piano (1952–1992), String Quartet no. 1 (1945), String Quartet no. 3 (1987), and Piece for Small Orchestra no. 2 (1985).

Nancarrow died on August 10, 1997, apparently from heart failure, at his home in Mexico City.

In 2012, a documentary called Conlon Nancarrow: Virtuoso of the Player Piano, written and directed by James Greeson, premiered in Little Rock (Pulaski County).

For additional information:

Carlsen, Philip Caldwell. “The Player Piano Music of Conlon Nancarrow: An Analysis of Selected Studies.” PhD diss., City University of New York, 1986.

Gann, Kyle. The Music of Conlon Nancarrow. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Greeson, James R., and Gretchen B. Gearhart. “Conlon Nancarrow: An Arkansas Original.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 54 (Winter 1995): 457–469.

Hocker, Jürgen. Encounters with Conlon Nancarrow. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2012.

———. “My Soul Is in the Machine—Conlon Nancarrow—Composer for Player Piano—Precursor of Computer Music.” In Music and Technology in the Twentieth Century, edited by Hans Joachim-Braun. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

Scrivener, Julie A. “Representations of Time and Space in the Player Piano Studies of Conlon Nancarrow.” PhD diss., Michigan State University, 2002. Online at https://d.lib.msu.edu/etd/31921 (accessed October 27, 2023).

Williams, Nancy A., ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Gretchen B. Gearhart

Fayetteville, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Music and Musicians

Music and Musicians World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Conlon Nancarrow

Conlon Nancarrow  Conlon Nancarrow

Conlon Nancarrow  "Prelude and Blues" by Conlon Nancarrow

"Prelude and Blues" by Conlon Nancarrow

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.