calsfoundation@cals.org

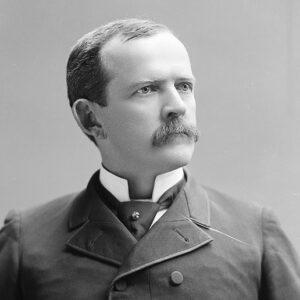

John Henry Rogers (1845–1911)

John Henry Rogers was a Civil War Confederate hero, a lawyer in Fort Smith (Sebastian County), a four-term Congressman, and a United States District Court judge for the Western District of Arkansas.

John Rogers was born on October 9, 1845, in Bertie County, North Carolina. His father, Absolom Rogers was a successful planter and slaveholder. In 1861, when Rogers was fifteen years old, he became the drillmaster for a company of home guards, and in March 1862, he was mustered into Company H, Ninth Regiment, Mississippi Volunteers, as a private soldier. Rogers served in the same regiment until it was surrendered at Greensboro, North Carolina, on May 1, 1865. He saw a considerable amount of action and was twice wounded, in Kentucky and in Tennessee. Rogers was awarded a battlefield commission as first lieutenant for gallantry at Franklin, Tennessee; he was nineteen years old at the time.

At the end of the war, Rogers walked back nearly a thousand miles from North Carolina to his family’s home in Mississippi, where he immediately studied to enter college. In 1867, he transferred to the junior class of the newly reopened University of Mississippi, graduating with the class of 1868. During the summer of 1867, and throughout his senior year, Rogers studied law and was admitted to the bar at Canton, Mississippi, in the summer of 1868. He took a job as a schoolteacher and continued his private law studies until he moved to Fort Smith and began practicing law in January 1869.

Rogers joined Judge William Walker’s law office in Fort Smith in 1869 and became a partner two years later. The partnership lasted until 1874, when Rogers went into solo practice. When the Twelfth Judicial Circuit was created in 1877, he was elected circuit judge. Rogers served two terms, and in 1882, he resigned to run for U.S. House of Representatives. He was elected and served until March 1891. The press regularly reported on Rogers’s speeches on the floor of Congress. His background as a Confederate war hero plus his imposing demeanor cast him in the role of a leading spokesman for the white Southern point of view. Like most Southerners in the Reconstruction era, Rogers was opposed to legislation favoring rights for former slaves, and he worked to defeat a bill intended to protect the voting rights of African Americans.

After the second of his four terms in Congress, Rogers became a member of the Committee on the Judiciary and made that his primary focus. He was very active in writing and securing passage of an act reforming federal criminal procedure and claimed credit for a statutory reform granting the writ of error to persons convicted of federal felonies. Prior to this enactment, there was no mechanism for appealing felony convictions beyond the Circuit Court of Appeals. In Arkansas, where Judge Isaac Parker sat both as a trial judge and on the Court of Appeals for criminal cases from Indian Territory, he was the “final word” in capital cases (very few federal courts other than Parker’s heard criminal cases). After 1889, with the writ of error available, a number of Parker’s death sentences were appealed to the Supreme Court, and many were reversed by the high court.

Rogers married Mary Gray on October 8, 1873. The couple had five children, including a daughter who died during childhood.

In March 1891, Rogers announced that he would retire from Congress and resume his law practice in Fort Smith. He was the chairman of the Arkansas delegation to the Democratic National Convention in 1892, where he was a leading supporter of Grover Cleveland, and after Cleveland was elected, Rogers lobbied for several presidential appointments, none of which materialized.

President Grover Cleveland appointed Rogers to the federal district bench at Fort Smith on November 27, 1896, after the death of Judge Isaac C. Parker. As a practicing lawyer, Rogers enjoyed a reputation of honesty, integrity, and very aggressive advocacy. His reputation as a federal judge was the same. His tenure on the court was quite different from that of Judge Parker, as most of the criminal cases arising in Indian Territory were handled by new courts; like most federal district court judges at the time, Rogers heard mostly civil cases.

His background as a Confederate veteran, politician, and U.S. District Judge made Rogers a popular speaker on the Civil War. Rogers spoke in New Orleans at the 1903 convention of the United Confederate Veterans. The thrust of Rogers’s oration was that the secession of the Confederate states was perfectly lawful under the Constitution and that no “treasonous” blame should be attached to the Southern states. Rogers also, however, spoke of the result of the war being beyond question, with the South now fully reconciled to the Union. Finally, he spoke of the Reconstruction era in terms of the real “lawless” period in the history of the war.

His speech was so well received by the Confederate veterans that the organization printed it in pamphlet form, under the title, “The South Vindicated.” The pamphlet was forty pages long and included a portrait of Rogers, along with a sketch of his life.

On April 5, 1911, Rogers traveled to Little Rock (Pulaski County) to hear cases for Judge Jacob Trieber, who was overburdened with a complex case involving railroad rate regulation. Rogers caught a bad cold during a hunting trip just before going to Little Rock. The cold persisted, but he continued to hear Trieber’s cases. On the morning of April 17, 1911, Rogers did not appear in court. Trieber and others found him dead in his hotel room, apparently from a heart attack. He is buried at Oak Cemetery in Fort Smith.

For additional information:

“In Memoriam: John Henry Rogers, 1845–1911.” Forth Smith, AR: Calvert-McBride Co., 1912.

“Judge J. H. Rogers Found Dead in Bed.” Arkansas Gazette, April 18, 1911, pp. 1, 3.

Morton Gitelman

Fayetteville, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Law

Law Politics and Government

Politics and Government Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 J. H. Rogers

J. H. Rogers  John Henry Rogers

John Henry Rogers

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.