calsfoundation@cals.org

Green Walter Thompson (1847–1902)

Green Walter Thompson was a major African-American political leader and businessman in Little Rock (Pulaski County) from the end of the Civil War until his death.

Green Thompson was born Green Elliott, a slave on the Robert Elliottt farm in Ouachita County. Nothing is known of his early life, though his tombstone lists a birth date of August 15, 1847. A birth year of 1848 is estimated from documents accumulated later in his life. The 1880 census records him as a “mulatto,” so it is likely a white man fathered him. His mother eventually married a slave named Thompson, and Green Elliott took his stepfather’s name.

While a teenager, he married a slave named Dora Hildreth; they soon had a baby girl. He left Ouachita County shortly after Christmas 1865 (after the end of the Civil War) and set out to build a new life in the capital, leaving behind his wife and newborn child.

Little Rock was filled with thousands of freedmen at the end of the Civil War, and Thompson prospered in his new environment. By 1871, he was in the grocery business. Soon, he opened a saloon and later opened a feed store. Like others of the city’s emerging black elite, Thompson invested in real estate, and by 1895, he owned a real estate company. One of his major assets was Thompson Hall, a large brick building with a public meeting hall, the scene of black social and political events.

Having a “before the war family” (as Thompson was once quoted as referring to Dora and his child) did not prevent him from getting married again and starting a family in Little Rock. By 1880, he was married to Darthulia W. Thompson and the father of two sons, the first named Green Walter Thompson Jr. This child apparently died at an early age; Darthulia died in 1896. A year and a half later, the forty-eight-year-old widower married twenty-year-old Mary Fairchild.

While still in his twenties, Thompson won his first elective office. In 1875, he was elected the Sixth Ward alderman on the Little Rock City Council. He served on the council for eighteen years, a record tenure for African Americans that was not surpassed for almost a century.

The twenty-year period after the Civil War was an exciting time for black voters. A few years earlier, they were slaves, not citizens; now they were a political force in Little Rock. This was especially true in the Sixth Ward.

Once elected, Little Rock aldermen usually were occupied with mundane matters. City government dealt mostly with the delivery of basic services. A certain egalitarian informality prevailed among council members, allowing for a relatively free exchange of ideas. Partisan confrontations occurred occasionally. In 1878, the white Democratic majority on the council convened in a court of impeachment to remove incumbent Republican police judge W. J. Warwick, who was charged with embezzlement. Though Thompson and fellow black Republican Isaac Gillam fought the effort, the judge was removed from office. In April 1878, Thompson suffered a more painful setback when he nominated a black political ally, William Rector, for city sanitary policeman. Thompson and Gillam recruited the votes of two white Democratic aldermen, but a white candidate was selected instead of Rector.

In 1888, Thompson accepted his party’s nomination for the state House of Representatives from Pulaski County. With the country caught in a prolonged agricultural depression and with political orthodoxy under challenge, the 1888 election was a great event in Arkansas’s political history. The incumbent Democratic Party fought desperately to stave off defeat, and voting irregularities were common. The Pulaski County results were so tainted (more than 1,000 false ballots were discovered) that a recount was undertaken. In February 1889, after a public outcry, all of the local Pulaski County Democratic incumbents resigned, and Thompson and the other Republicans were seated. Thompson did not run for reelection, but in 1890, he was the unsuccessful Union-Labor Party nominee for state senator.

As the Gilded Age gave way to the more strident 1890s, Thompson and other black politicians battled discrimination, segregation, and disfranchisement. The warm relationship between black citizens and the Republican Party slowly degenerated as the party of Abraham Lincoln and Charles Sumner became the party of Mark Hanna and William McKinley, of big business and political expediency.

In 1891, the Arkansas General Assembly passed new laws that consolidated the voting process in the hands of the Democratic Party. These “reforms” curtailed the number of black citizens who voted in 1892. Still, the Democrats realized that the 1891 election law would not be enough to purge the black aldermen from the “Bloody Sixth Ward,” as the Arkansas Gazette characterized Thompson’s solidly black and staunchly Republican ward. Thus, in 1893, the city eliminated the ancient system of electing aldermen by ward and implemented citywide at-large elections. Thompson waged a vigorous campaign for reelection, but Democrats swept into every position on the council, with Thompson falling 514 to 1,955. No other black candidate won election to the council until 1969.

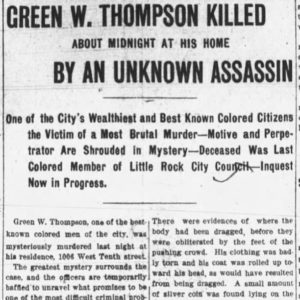

Thompson died on March 20, 1902. He was returning home at around midnight from a meeting when an assailant killed him with an ax as he stabled his horses. Although family members initially were charged, no one was convicted.

For additional information:

Dillard, Tom W. “Enigmatic Black Pol Bucked Post-Civil War System.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. November 21, 2004, p. 5H.

———. “No One Ever Stood Trial for Killing Green Thompson.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. November 28, 2004, p. 5H.

Tom W. Dillard

University of Arkansas Libraries

African American Legislators (Nineteenth Century)

African American Legislators (Nineteenth Century) Green Thompson Murder

Green Thompson Murder

I am one of the great-great-grandchildren of Green Walter Thompson. The slave wife who he had a daughter with was also named Dora with a middle name of America. Dora America was sent to Texas, and she married John Horsley in 1879.