calsfoundation@cals.org

Daniel Phillips Upham (1832–1882)

Daniel Phillips Upham was an active Republican politician, businessman, plantation owner, and Arkansas State Militia commander following the Civil War. He is perhaps best remembered, and often vilified, for his part during Reconstruction as the leader of a successful militia campaign against the Ku Klux Klan in the Militia War from 1868 to 1869.

D. P. Upham was born in Dudley, Massachusetts, on December 30, 1832, to Clarissa Phillips and Josiah Upham. His mother died less than a week later at age 29. His father remarried Betsy Larned in March 1836, and the couple had four sons.

Upham received his education at Dudley’s public schools, and he married Massachusetts native Elizabeth (Lizzie) Nash on February 15, 1860. The couple eventually adopted a daughter, Isabel.

Upham struggled as the owner of a bluestone—building material—business in New York City. He left his family and arrived at DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) in April 1865, where his former business associate, Brigadier General Alexander Shaler, was the commanding officer. General Shaler gave Upham the necessary access to the proper licenses for entering the businesses that Upham hoped would relieve his debts. Soon, Upham had profitable interests in two saloons, a cotton plantation, and two steamboats. In July 1865, he visited the Northeast to pay his debts, and he returned with his wife. The couple settled in Augusta (Woodruff County) where Upham owned a cotton plantation and a prosperous store.

Following the Congressional Reconstruction Acts of 1867, Upham was elected to represent Woodruff, Crittenden, and St. Francis counties in the Arkansas House of Representatives. Politically, Upham was a Radical Republican who supported Republican Governor Powell Clayton’s efforts to reshape Arkansas politically, socially, and economically. In the spring of 1868, the Ku Klux Klan, a loosely organized band of former Confederates and sympathizers upset by expansion of Black voting rights and the restrictions against former Confederates’ voting rights, began to retaliate by terrorizing white and Black Republicans. The state legislature approved the creation of a state guard and reserve militia in July 1868, and Clayton ordered several counties, including Woodruff, to muster up militias in late August.

Upham’s popularity with freedmen and his business success stirred resentment with southern whites, and he became the target of Woodruff County’s Klan. Tensions mounted with political assassinations in nearby counties and public displays of force by the local Klan and Upham’s militia. After numerous threats and reports of nightly Klan surveillance of his home, Upham and F. A. McClure, Woodruff County’s registrar, were ambushed and injured on October 2, 1868.

Governor Clayton canceled elections for president, U.S. Congress, and legislative vacancies in Woodruff County and ten other counties. Clayton declared martial law in those areas and divided the state into four military districts. After Joseph Brooks turned down the position, Clayton selected Upham to command the northeast military district. The burning conflict would later be termed the Militia War.

Upham set up headquarters near federal troops at Batesville (Independence County) in an effort to stabilize the region. His forces grew to 1,000 white and Black troops. He returned to Woodruff County leading more than 100 white troops to face the local Klan led by Confederate veteran Colonel A. C. Pickett. Pickett and his men managed to overrun and pillage Upham’s plantation, but Upham prevented the occupation of Augusta by taking several Klan sympathizers hostage and threatening to kill them if the Klan did not disperse. The tactic seemed to work, but later 100 Klansmen ambushed him and his men. In a series of skirmishes, Upham faced off and defeated the Klan in Woodruff County.

Upham’s resolve, tactics, recruitment of Black troops, and occupation of his own county proved controversial and politically divisive. In April 1875, his former enemies in Woodruff County took their revenge just as Democratic Redeemers ended Reconstruction. Upham was tried for the murder of two men during the Militia War. Although he was acquitted and vindicated of wrongdoing, Upham remained an object of scorn in local and standard state histories well into the twentieth century.

Upham and his wife left Woodruff County and settled in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1869. He invested in real estate, continued to serve in the Arkansas State Militia, and was a clerk in the Pulaski County Chancery Court. In October 1870, he was appointed brigadier general in command of the Seventh District in central Arkansas. He also served in a series of battles against ex-Confederates in Pope County in 1872. In May 1873, Republican governor Elisha Baxter dismissed him from the Arkansas State Militia along with other men with ties to Powell Clayton. A year later, in the haze of the Brooks-Baxter War, Upham sided with Joseph Brooks and took command of a company of men in Brooks’s unsuccessful attempt to claim the governorship. In the 1870s, he also served on the city council and school board of Little Rock.

In July 1876, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Upham U.S. marshal for the Western District Court presided over by Judge Isaac C. Parker in Fort Smith (Sebastian County). At first, his appointment raised the specter of his controversial past, but Upham served with distinction and received wide public support. His service as U.S. marshal ended when Arkansas’s former Republican U.S. senator Stephen Dorsey plotted effectively to have him replaced in June of 1880. Upham fought for his reappointment but failed due to opposition from his former ally, Powell Clayton.

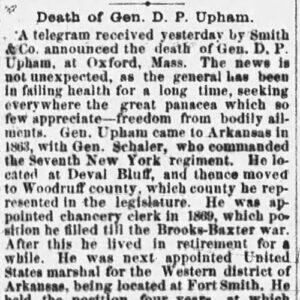

In November 1882, with his health failing, he visited family in Massachusetts. He died of “consumption”—that is, tuberculosis—at his father’s house in Dudley, Massachusetts, on November 18, 1882, and was buried in Little Rock’s Oakland Cemetery. His wife and daughter are interred next to him.

For additional information:

D. P. Upham Collection. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Obituary of Daniel Phillips Upham. Arkansas Gazette. November 22, 1882, p.4.

Obituary of Daniel Phillips Upham. Worcester Evening Gazette. November 22, 1882, p. 2.

Rector, Charles J. “D. P. Upham, Woodruff County Carpetbagger.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Spring 2000): 59–75.

Blake Wintory

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Military

Military Politics and Government

Politics and Government Daniel Phillips Upham Death Story

Daniel Phillips Upham Death Story

Daniel Upham was also, like almost all carpetbaggers, the chief reason that Reconstruction lasted so long. After the Union victory, he and his ilk wanted to make the South pay for the Civil War and did so by being as brutal and heavy-handed as he could. I feel he is NO ONE to be admired; he in fact should bring shame upon his descendants and the Union for behaving the way he did, instead of letting the Southerners come back into the Union peacefully, as Lincoln had wanted. The Klan should not have been tolerated at all, but Upham and his thugs killed and beat many Southerners for just being SUSPECTED Klansmen, which was worse, because they were denied a trial. As a Southerner myself (Mississippi), I am thoroughly ashamed and revolted by Mr. Upham because he was, in many ways, WORSE than those he fought against and used tactics as bad as those he professed to hate.