calsfoundation@cals.org

Historic Preservation

Arkansas has an active preservation community with a notable success record in saving buildings, sites, and neighborhoods. The tools successfully used in Arkansas were developed on the national stage and successfully transplanted to the state.

The first preservation achievements were the result of strong individual leadership focused on saving landmark buildings. The first major success was what is now called the Old State House (Arkansas’s first state capitol building), which was constructed beginning in 1833. It remained the capitol until 1911, when construction of the present Arkansas State Capitol was sufficiently completed for occupancy. Since 1901, the legislature and the governor had debated the idea of selling the old building once it was vacated. This proposal garnered serious attention again in 1904, 1907, and 1909. Each time, the bills were defeated, but the issue remained unresolved until 1912, when the University of Arkansas Medical Department (now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) moved into the building, using parts of the deteriorating structure until 1935. The Arkansas Department of the American Legion occupied other portions of the building beginning in 1921, renaming it the Arkansas War Memorial. Over the years, the American Legion and other patriotic organizations sought state funding to prevent the collapse of the Old State House; legislation to provide such funding was finally passed in 1947. After four years of restoration work, costing the state $350,000, the Old State House was opened to the public. Further efforts at restoration have required additional funding over the years. The structure was home to the Arkansas History Commission (now called the Arkansas State Archives) until 1979.

The second landmark to be saved by the advocacy of a strong lobby group was the 1836 Hempstead County Courthouse in Washington. Built as a frontier county courthouse, it became the Confederate capitol of Arkansas during the Civil War. While much of Arkansas was occupied by the Union army, the southwest corner remained in Confederate hands. The Confederate state government occupied the courthouse building, although some legislators were unable to come to Hempstead County. This courthouse was replaced with a new building in 1874, and the old building was put to several uses, including a public school. By 1922, the building was in poor condition, and the citizens of Hempstead County sought legislative support to save the building. Not until 1929 was the Wartime Memorial Commission created by the Arkansas legislature and money appropriated to restore the building. Most of the members of the commission were members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

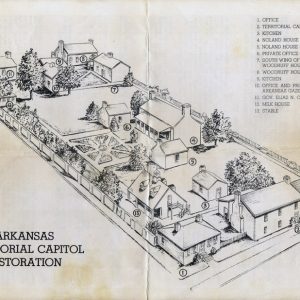

Led by Louise Loughborough, a third landmark partnership between a private advocacy group and the Arkansas legislature was the creation of the Arkansas Territorial Restoration, now called the Historic Arkansas Museum (HAM). Part of the oldest neighborhood in the city, the museum contains the oldest building still standing in central Arkansas, the Hinderliter House and Tavern, constructed in 1827, as well as three 1830s houses and a variety of other historic and reconstructed structures, in addition to a visitors’ center, galleries, a gift shop, and more. By the late 1930s, the half city block with the historic buildings was in poor condition and slated for destruction. Loughborough took the lead to save the buildings and lobbied the governor, legislature, and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). She and her committee were successful, and the museum opened in 1941. There have been many expansions and refinements since that time. Each of the three landmarks followed the model of state ownership and funding, with an executive director and a public board or commission.

In February 1941, David Yancey Thomas announced his intention to organize a permanent historical association and accompanying journal. John Hugh Reynolds was elected president of the Arkansas Historical Association (AHA). Thomas was chosen as editor of the AHA’s journal, and the first issue of the Arkansas Historical Quarterly went to press in March 1942.

Archaeology is a component of historic preservation projects, not only working in tandem with architects and planners, but also with a focus on Native American sites and artifacts. The focus on Native American sites began in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and involved reconnaissance and documentation and then removal of many artifacts from the state to East Coast institutions. The second phase was in-state research and collecting. Although scattered efforts took place earlier, the first comprehensive organization of such efforts was the founding of the Society for Historical Archaeology in 1967. The goal was to improve the quality of archaeological work and to foster cooperation among local museums, enthusiasts, and others. The acquisition of Native American sites for purposes of preservation and education was rarely done, with the Menard-Hodges Site, situated on the lower Arkansas River, as a rare exception.

The state purchased several important sites in order to preserve and interpret them. These are the Knapp Mounds, now called the Toltec Mounds Site, located near Scott (Pulaski and Lonoke counties), and the Parkin Site in east-central Arkansas. A number of other sites are in public hands, but in those cases, the land was acquired for recreational, natural, or other purposes, with the archaeological value not the primary reason for the action. A number of historic sites are in that category, such as Historic Washington State Park, Davidsonville Historic State Park, and other national and state properties that have turned out to be important archaeological sites even though that was not the purpose of their initial acquisition.

The first professional archaeologist hired to reside in Arkansas was Dr. Charles McGimsey, who joined the faculty of the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) in 1957. The Arkansas Archeological Society was founded in 1960, with Samuel C. Dellinger as its first president. Dellinger had been teaching courses in anthropology at UA since the 1920s as a member of the Department of Zoology, and he also was curator of the University of Arkansas Museum. The society was joined by the Arkansas Archeological Survey in 1967. Created by Act 39 of the Arkansas General Assembly, the Arkansas Archeological Survey maintains eleven research stations in Arkansas and publishes research reports and technical reports, as well as a research series and a popular series, to inform the public about archeological research in Arkansas.

Preservation in Arkansas generally followed the course of preservation at the national level. The National Trust for Historic Preservation was founded in 1947, and President Harry S. Truman signed legislation creating its federal charter in 1949. The organization helped develop and lobby for the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which created procedures and standards that could be applied anywhere in the nation. As of 2015, the trust today has more than 750,000 members and supporters and thirteen field offices; Arkansas is part of the southwest region and has a very active advocacy, volunteering, and financial support program.

One of the results of the trust’s advocacy and support was the creation of statewide preservation organizations in each state, such what is now Preserve Arkansas, which is the only statewide nonprofit organization focused on preserving Arkansas’s architectural and cultural resources. The organization was founded in 1981, and the size of the organization has fluctuated over the years. As of 2015, it has an executive director, and its programs include an annual conference, the Ramble (an all-day tour in some part of the state), advocacy efforts, three small endowments, and the Arkansas Most Endangered Places Program.

Preservation, at most levels, is mostly achieved by a small group of people coming together. The tier below the state level is the local. Three local organizations in particular have long track records: the Pioneer Washington Restoration Foundation, the Quapaw Quarter Association, and the Belle Grove organization.

In the 1950s, the townspeople of Washington, in southwest Arkansas, recognized that their town was an important historic site and that many of its historic buildings were in poor condition. In April 1958, discussions began to organize the Pioneer Washington Restoration Foundation to promote the restoration of some of the old historic town. As a result, a family with Washington roots pledged to underwrite the first restoration work if the club could be changed to a nonprofit corporation. This was done later that year, and the Pioneer Washington Restoration Foundation, Inc., was created. It is still operating and is the oldest preservation organization in Arkansas.

The Quapaw Quarter Association (QQA) began in 1961 as the Significant Structures Technical Advisory Committee. This was an advisory committee on historical and architectural landmarks, advising the urban renewal agency. This name was changed in 1962 to the Quapaw Quarter Committee, and the group was broadened into a membership organization, the Quapaw Quarter Association, in 1968.

The Belle Grove organization in Fort Smith (Sebastian County) helped to have the Belle Grove Historic District placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.

While local and statewide membership organizations such as the QQA are private entities, the State of Arkansas has a major role in preservation in Arkansas. The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 was the catalyst for the appointment of the first State Historic Preservation Organization, then in the Department of Parks and Tourism. This was followed in 1975 by the creation of the Department of Arkansas Natural and Cultural Heritage, which in 1985 was renamed the Department of Arkansas Heritage (DAH), now the Division of Arkansas Heritage. The DAH serves the preservation community through many programs and facilities, and many museums incorporate historic structures within their programs. In addition to the Old State House and the Historic Arkansas Museum, the Delta Cultural Center in Helena-West Helena (Phillips County) is a museum that utilizes a historic building and offers a variety of interpretive programs. The Mosaic Templars Cultural Center in Little Rock (Pulaski County) aimed to do the same, but when the original building was destroyed by fire in 2005, the DAH and the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center recreated the structure. Of all the DAH programs, the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program (AHPP) provides the widest and most supportive programs. Grants, tax incentives, easements, and technical assistance are some of the tools available in the AHPP arsenal of support.

A remarkable tool for funding preservation projects is the Arkansas Natural and Cultural Resources Council, which distributes the Real Estate Transfer Tax. This funding has improved the quality of preservation work in Arkansas. The State Parks Division also oversees a number of historic facilities. The largest is Historic Washington State Park, which includes forty-three buildings, twenty-three of which are considered historic. Twenty-two Arkansas State Parks contain nationally recognized structures or properties, and thirteen have museums.

The public universities in Arkansas contain numerous historic buildings; at least three teach some aspect of preservation in their curriculum. UA has restored Vol Walker, Old Main, Carnall Hall, and the chemistry building. In addition, some of the faculty members teach introductory preservation courses and architectural history. The University of Arkansas at Fort Smith (UAFS) restored the Drennen House in Van Buren (Crawford County), establishing the Drennen-Scott Historic Site as a public museum. Arkansas State University (ASU) in Jonesboro (Craighead County) has developed a Heritage Studies doctoral program and restored several historic properties with museums for the interpretation of them; these include the Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum, the Southern Tenant Farmers Museum, and the Lakeport Plantation.

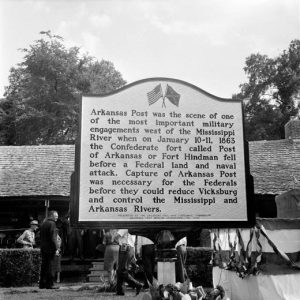

Finally, there are a number of federally owned historic buildings and sites in Arkansas, including the Arkansas Post National Memorial, Fort Smith National Historic Site, and Bathhouse Row in Hot Springs (Garland County). Also included are federal courthouses, particularly the two in Little Rock, and the Pea Ridge National Military Park.

For additional information:

Division of Arkansas Heritage. https://www.arkansasheritage.com/ (accessed February 15, 2024).

Fagette, Paul H., Jr. “The Founding of the Arkansas Archeological Survey.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 53 (Autumn 1994): 290–311.

Hansen, Gregory. “KASU FM 91.9’s ‘Bluegrass Monday’: Performing Intangible Cultural Heritage and Fostering Historic Preservation in Arkansas, USA.” In Sustaining Support for Intangible Cultural Heritage, edited by Shihan de Silva Jayasuriya, Mariana Pinto Leitão Pereira, and Gregory Hansen. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022.

Kwas, Mary L. “The Growth of Historical Archaeology and Its Impact in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 67 (Winter 2008): 329–341.

———. A Pictorial History of Arkansas’s Old State House: Celebrating 175 Years. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011.

Nixon, Dana Daniels. “History of the Quapaw Quarter Association.” Pulaski County Historical Review 57 (Summer 2009): 44–57.

Preserve Arkansas. https://preservearkansas.org/ (accessed February 15, 2024).

Williams, Charlean Moss. The Old Town Speaks: Recollections of Washington Hempstead County, Arkansas; Gateway to Texas, 1835, Confederate Capital, 1863. Houston, TX: Anson Jones Press, 1951.

Worthen, William B. “Restoring the Restoration.” History News, November 1984, pp. 6–11.

Charles Witsell Jr.

Little Rock, Arkansas

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Antiquarian and Natural History Society of Arkansas

Antiquarian and Natural History Society of Arkansas Arkansas Register of Historic Places

Arkansas Register of Historic Places Civil War Archaeology

Civil War Archaeology Jefferson County Historical Society

Jefferson County Historical Society Oak Grove Rosenwald School

Oak Grove Rosenwald School Arkansas Post Marker

Arkansas Post Marker  Arkansas State Archives

Arkansas State Archives  Arkansas Territorial Capitol Restoration Map

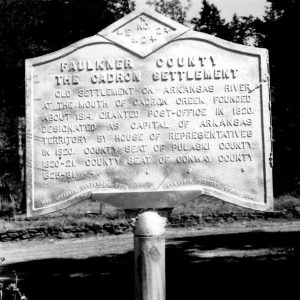

Arkansas Territorial Capitol Restoration Map  Cadron Settlement Marker

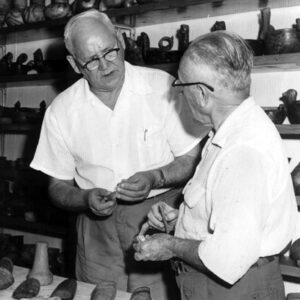

Cadron Settlement Marker  Samuel Dellinger

Samuel Dellinger  Clara Eno

Clara Eno  Fort Smith National Historic Site

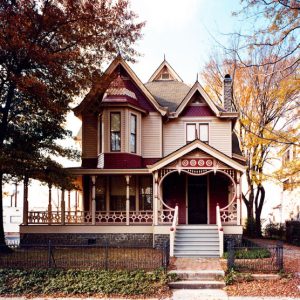

Fort Smith National Historic Site  Frederick Hanger House

Frederick Hanger House  Heritage Poster

Heritage Poster  Jacob Wolf House

Jacob Wolf House  Vera Key

Vera Key  Lakeport Plantation

Lakeport Plantation  Lakeport Plantation

Lakeport Plantation  Louisa Loughborough

Louisa Loughborough  Old Independence Regional Museum

Old Independence Regional Museum  Old State House

Old State House  Pea Ridge National Military Park Battlefield

Pea Ridge National Military Park Battlefield  Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park

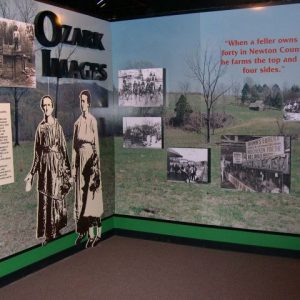

Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park  Shiloh Museum of Ozark History Exhibit

Shiloh Museum of Ozark History Exhibit

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.