calsfoundation@cals.org

Freedmen's Schools

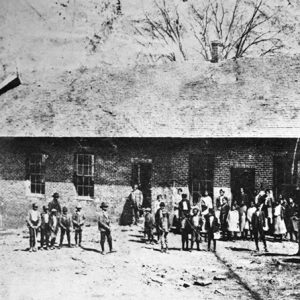

Freedmen’s schools in Arkansas were created as early as 1863 in areas occupied by Union forces to provide for the education of newly freed slaves during the Civil War and in the Reconstruction period that followed. These schools were first run by teachers from the American Missionary Association (AMA) and the Quakers—particularly the Indiana Yearly Meeting of Friends. Early schools existed in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Little Rock (Pulaski County), and Helena (Phillips County), all areas with large populations of freed slaves. The federal government soon became involved in providing education for the freed slaves, and in 1865 the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) assumed responsibility for educating former slaves. AMA and Quaker teachers began working under the supervision of this federal agency.

After its inception, the Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas established more than twenty-five field offices throughout the state—mostly in the eastern and southern portions of Arkansas. An 1867 report listed at least twenty-seven Freedmen’s Bureau teachers in the state of Arkansas. Freedmen’s Bureau agents visited every place where a school might be established and organized a meeting of the freedmen to advise them in the election of a five-member African-American school board. Money for the erection, repair, or rental of schoolhouses came from a bureau fund administered by the assistant superintendent of education. Bureau regulations at the time stated that at least one acre of land in a healthy, central location was required for each school and that title to the land had to be vested in the black school board. The local freedmen were generally responsible for erecting the school building, but the assistant superintendent would help repair or rent already existing buildings. It is estimated that for 1865–66, African Americans furnished about a third of the cost for operating their schools, with private aid from the North making up the balance. The federal government often paid only a fraction of the cost of the Freedmen’s Bureau schools.

Some teachers faced planter opposition to black education, in addition to problems with inadequate housing and a lack of appropriate buildings for instruction. For example, at Warren Plantation, near Pine Bluff, a Mrs. Pierce held her first classes in a building occupied by a family of six former slaves. The structure had a single door but no windows and was unbearably cold. A plantation manager, however, later built a new schoolhouse with two doors and a window.

William Hubbard, who taught on the Green Adkins Plantation near Pine Bluff, noted that white planters charged such high prices for goods needed by black workers that the black men had little or no money left to pay tuition for the school. Hubbard reported that many of the planters harbored the hope that the freedmen would become so poor and demoralized that they would return to slavery. However, some white planters favored federally funded schools for freedmen and hoped that former slaves would remain on their old plantations and be obedient workers in the postwar economy. Few of these planters, however, offered to fund the schools themselves.

The peak of Freedmen’s Bureau education efforts came in 1868, when the number of bureau-sponsored schools reached twenty-seven, with thirty-three teachers and 1,613 pupils. In the same year, groups such as the AMA and the Quakers operated an additional twenty-four Sabbath schools with 118 teachers and 1,847 students, as well as two high schools with a total of 134 students. With the aid of the AMA, Freedmen’s Bureau schools spread to several areas throughout Arkansas, including Sebastian, Washington, Jefferson, and Hot Spring counties. After Arkansas was readmitted to the Union in 1868, the bureau helped freedmen maintain ownership of their school property and buildings. The various schools overseen by the Freedmen’s Bureau enabled an estimated 40,000 African Americans in Arkansas to achieve basic literacy and math skills. These skills were indispensable for former slaves dealing with white planters who tried to draw up unfair labor contracts or incorrectly tabulate debts or charges at country stores.

In 1868, a new Republican government took up the challenge of raising revenues for a state public school system, unlike the earlier governments that had fought these increases. The creation of a public school system effectively ended the role of the Freedmen’s Bureau in black education in Arkansas, and General A. C. Smith soon drew up plans to turn over Freedmen’s Bureau schools to the state. In most cases, AMA missionaries and Quakers signed contracts with the new school boards so that there would be continuity between earlier educational efforts and the new public school system.

The AMA and Quakers, in conjunction with some former Freedmen’s Bureau teachers, continued working in the new public school system in Arkansas until 1878. Historians point to a failed mill tax provision that year as ending the career of the last AMA educator in Arkansas, M. W. Martin of Pine Bluff. The failed mill tax typified the attitude of many Democratic politicians from the 1870s onward, who oversaw cuts in public funding for schools that disproportionately affected African Americans. Although public schools technically existed in Arkansas after 1878 for African Americans, there was a general decrease in the last part of the nineteenth century in access to education for black Arkansans.

For additional information:

DeBlack, Thomas. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Finley, Randy. From Slavery to Uncertain Freedom: The Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Lovett, Bobby L. “African-Americans, Civil War, and Aftermath in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 54 (Autumn 1995): 304–358.

Pearce, Larry Wesley. “The American Missionary Association and the Freedmen in Arkansas, 1863–1878.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Summer 1971): 123–144.

Rotrock, Thomas. “Joseph Carter Corbin and Negro Education in the University of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Spring 1971): 277–314.

Ryan Jordan

National University

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Education, Elementary and Secondary

Education, Elementary and Secondary Henderson School

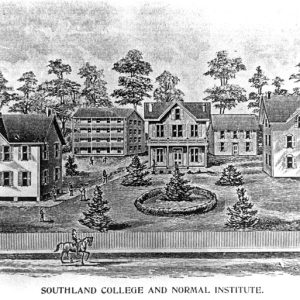

Henderson School  Southland College

Southland College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.