calsfoundation@cals.org

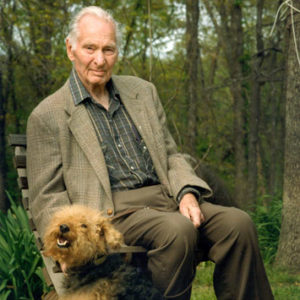

Harold Edward Alexander (1909–1993)

Harold Edward Alexander was a conservationist and stream preservationist who was a proponent of conservation and wildlife management in Arkansas from the 1950s to the 1980s. The Harold E. Alexander Wildlife Management Area in Sharp County was named in recognition of his service to Arkansas conservation and his long career with the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission (AGFC). He has been called “the father of Arkansas conservation.”

Harold Alexander was born on November 23, 1909, in Lawrence, Kansas, the son of Edward Alexander, the treasurer for the city of Lawrence, and Ruby Pringle Alexander. Alexander was the oldest of four boys. He went to Lawrence High School and graduated from the University of Kansas in 1939 with two years of studies in the fine arts and a BA in zoology. He used both skills in his career. Alexander married Virginia Schooling on September 14, 1940. They had four children. He and his wife moved to Texas so that he could study wildlife management at Texas A&M University, receiving an MS in 1942.

His first professional job was as a wildlife biologist with the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, conducting game surveys in south Arkansas. Alexander was drafted into the military in 1942, interrupting his employment with AGFC. He served stateside during World War II with the U.S. Army Air Forces, particularly at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, doing scientific drawings.

Upon release from the military, Alexander wanted to return to Arkansas, but finding no job waiting, he took a position with the Kentucky Department of Fish and Game. In 1950, he accepted a biologist position with AGFC and moved to Conway (Faulkner County), where he lived the rest of his life. He later was head of environmental planning for the state Department of Planning but returned to work for AGFC as a biologist and environmental consultant until his health finally led to his retirement from public service in 1991.

Alexander’s conservation concerns were far ranging, especially in regards to stream preservation, but also wetlands protection, responsible use of the land for future generations, wildlife research, and the need to communicate and share scientific studies. He helped steer wildlife management in Arkansas in deer management and species restoration. He is credited with the discovery of brain worms in the southeastern whitetail deer in the late 1960s. Alexander’s work influenced the next generation of Arkansas conservationists and wildlife managers.

In Arkansas, Alexander supported protection for the Buffalo River and the Cache River, among other projects. Neil Compton, founder of the Ozark Society, credited Alexander as the one who alerted him to the extent of the dam impoundment program of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for Arkansas’s rivers. Working within the constraints of a state position (Alexander later wrote that his opposition to projects such as the proposed dam for the Buffalo River was “a dangerous activity for those of us in public jobs”), Alexander provided support for the preservation of Arkansas rivers and information and assistance to conservation groups around the state and nation, becoming a well-known figure in the movement.

Alexander had become alarmed by what he saw as rapidly vanishing free-flowing streams around the nation and began speaking out in support of stream preservation. In talks and writings, he asked public managers and planners to “save our open spaces, wild lands and natural streams and rivers before they are all sacrificed on the altar of our technology.” Alexander believed that too many streams were being transformed into artificial reservoirs without sufficient consideration of what he called “inherent recreational, intangible and quality values” that “cannot be estimated in dollar terms.”He was an early champion of the wild and scenic rivers concept. Although he saw many of his ideas become public policy, he continued to speak out for what he called the value of unaltered environments. Alexander’s words hang in the Tyler Bend Visitor Center at the Buffalo National River: “A stream is a living thing. It moves, dances and shimmers in the sun. It furnishes opportunities for enjoyment and its beauty moves men’s souls.”

Alexander received many awards, including a presidential citation in 1970 (signed by Richard Nixon) for his contributions to water resources conservation; the Conservationist of the Year Award for 1983 from the Arkansas Wildlife Federation (the award is now named for him); the Clarence W. Watson Award for 1983 from the Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies; and the Special Recognition Service Award in 1987 from the Wildlife Society.

Although diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, Alexander continued to work on conservation issues. He died on September 14, 1993, and is buried at Crestlawn Memorial Park in Conway. Alexander was inducted posthumously into the Arkansas Outdoor Hall of Fame in 1993.

For additional information:

Compton, Neil. The Battle for the Buffalo River. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Harold E. Alexander Papers. University of Central Arkansas Archives and Special Collections, Conway, Arkansas.

Heuston, John. “Arkansas’ Greatest Conservationist.” Arkansas Fish and Wildlife. April 1993, pp. 32–34.

Spencer, Jim, and Joe Mosby. “A Tribute to ‘The Father of Arkansas Conservation.’” Arkansas Wildlife 24 (Winter 1993): 12–13.

Williams, Nancy A., ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Suzanne Rogers

Buffalo National River

Harold Alexander

Harold Alexander

Harold Alexander was married to my mother’s sister Virginia, my aunt. I am so very proud of the work Harold accomplished in his zest for healing the rivers and streams in Arkansas. He and my aunt are gone now and having grown up thousands of miles away from their family, I cant say, sadly, that I knew them well. I can only offer up my genuine pride to say he was family. There are few men of his caliber left to move the mountains and streams and rivers he moved.