calsfoundation@cals.org

Flood of 1927

aka: Great Flood of 1927

aka: Mississippi River Flood of 1927

aka: 1927 Flood

The Flood of 1927 was the most destructive and costly flood in Arkansas history and one of the worst in the history of the nation. It afflicted Arkansas with a greater amount of devastation, both human and monetary, than the other affected states in the Mississippi River Valley. It had social and political ramifications which changed the way Arkansas, as well as the nation, viewed relief from natural disasters and the responsibility of government in aiding the victims, echoing the Hurricane Katrina disaster in the present day.

In largely agrarian Arkansas, the Flood of 1927 covered about 6,600 square miles, with thirty-six out of seventy-five Arkansas counties under water up to thirty feet deep in places. In Arkansas, more people were affected by the floodwaters (over 350,000), more farmland inundated (over two million acres), more Red Cross camps were needed (eighty of the 154 total), and more families received relief than any other state (41,243). In Arkansas, approximately 100 people died, more than any state except Mississippi. In monetary terms, the losses in Arkansas (totaling over $1 million in 1927 dollars for relief and recovery) surpassed any other affected state.

The Flood of 1927 had its origins both in nature and in man. In the late 1920s, technological advances kept pace with the growing economy. Heavy machinery enabled the construction of a vast system of levees to hold back rivers that tended to overrun their banks. Drainage projects opened up new, low-lying lands that had once been forests but had been left bare by the timber industry.

Feeling protected from flooding by the levees, farmers borrowed money with easy credit from banks booming with the record levels of the stock market. They expanded their fields to low-lying areas on their own property or moved to new lands that were fertile from centuries of seasonal flooding. They felt safe behind the levees and secure in selling their crops to new markets, now accessible by railroad, truck, automobiles, and even international shipping. The “buy now, pay later” mindset of the 1920s encouraged people, including farmers of modest means, to purchase washing machines and other labor-saving devices on installment plans. Even nature seemed to be cooperating, as the summer of 1926 brought rain instead of drought.

The spring of 1927, however, saw warm weather and early snow melts in Canada, causing the upper Mississippi to swell. Rain fell in the upper Midwest, sending its full rivers gushing into the already swollen Mississippi. Its destination, the Gulf of Mexico, acted as a stopper when it too became full. Then, in the South, it began to rain.

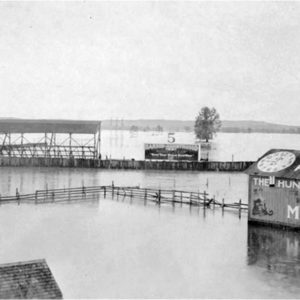

April 1927 saw record rainfall in Arkansas, with more than seven inches falling on Little Rock (Pulaski County) in just a few hours. There was no place for it to go because the ground was saturated. Lakes, rivers, and streambeds were full. The swollen Mississippi River backed up into the Arkansas, White, and St. Francis rivers. The White River even ran backward at one point as torrents rushed into it from the Mississippi.

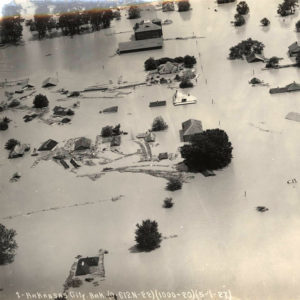

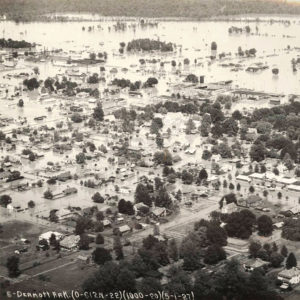

Levees could not hold, with every one between Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and Little Rock failing under the enormous surge of water. The September 1927 National Geographic said that the streets of Arkansas City (Desha County) were dry and dusty at noon, but by 2:00 p.m., “mules were drowning on Main Street faster than people could unhitch them from wagons.” Water poured in and had nowhere to go. Homes and stores stood for months in six to thirty feet of murky water. Dead animals floated everywhere. Rich Arkansas farmland was covered with sand, coated in mud, or simply washed away, still bearing shoots from spring planting.

Floods devastated Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Tennessee, but the worst destruction was in Arkansas. In some places, the Mississippi River was sixty miles wide. Almost twice as much farmland was flooded in Arkansas as in Mississippi and Louisiana combined.

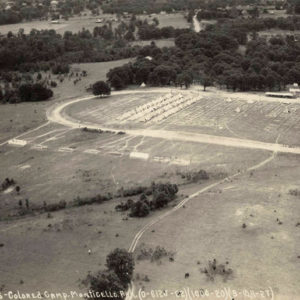

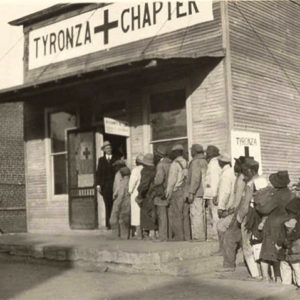

At first, modern technology seemed to help ease the disaster. Radios broadcasted warnings. Airplanes helped locate survivors clinging to rooftops or tree limbs. Motorboats aided the evacuation, and trains carried people to shelters on high ground. The American Red Cross, as well as fellow citizens, responded quickly, with emergency workers arriving by trains, trucks, and automobiles. Refugee camps, using Army tents and cots, were hastily built by the Red Cross, with one in Forrest City (St. Francis County) holding more than 15,000 of the homeless. But victims kept arriving from all around Arkansas—cold, sick, and hungry. Some found shelter in public buildings or other makeshift locations. Nearly all found themselves without food, water, or dry clothing. The segregated tent cities on high ground could barely hold them all. Disease ran rampant in the overcrowded camps. Conditions then worsened.

With the floodwater having nowhere to go, much of Arkansas remained under water through the spring and summer and into September of 1927. Farmers could not plant crops. The carcasses of thousands of dead animals lay rotting in stagnant pools. Mosquitoes found perfect conditions to breed that summer, carrying malaria and typhoid to refugee camps already burdened with dysentery and the threat of smallpox. Emergency workers at the camps were also shocked at the extent of pellagra, a vitamin deficiency disease brought on by lack of protein.

The death toll from all states devastated by the flood was placed by the Red Cross at 246. (Pete Daniel in Deep’n as it Comes places the number at 443.) But the number of people left without food, water, clothing, or work numbered almost 750,000.

There were racial and socio-economic ramifications in Arkansas as elsewhere. Out-of-state emergency workers clashed with local health officials and large planters over the extent and types of aid and to whom such aid should go. In some places, the Red Cross distributed aid directly to the victims. But in others, so as not to challenge the plantation system, relief supplies were given to the large planters, who were then in charge of distributing them to their sharecroppers.

Planters feared that their sharecroppers, both black and white and most deeply in debt, might not return home from the Red Cross camps, leaving them without enough labor to put crops in the fields when the land dried out. This led to a controversial mandate in which sharecroppers, particularly black sharecroppers, were admitted to and released from the camps only under the supervision of their planters. African Americans needed a pass to enter or leave the Red Cross camps. Some were forced at gunpoint by law enforcement officials to survive on the levees indefinitely in makeshift tents as water rose around them while would-be rescue boats left empty. They were forced by the National Guard with fixed bayonets to work on the levees, in addition to other flood relief efforts.

The Red Cross maintained refugee camps for flood victims through September 15, when many people, black and white, were finally able to return to their devastated land to try to survive the winter and start over with virtually nothing.

The Flood of 1927 took place when the rest of the country was enjoying the peak of Roaring Twenties prosperity. In Washington DC, the federal response under President Calvin Coolidge to the misery in the flooded South was simple: not one dollar of federal money went in direct aid to the flood victims.

The Flood of 1927 brought Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover into the spotlight as Coolidge’s appointee to chair local and voluntary relief operations, laying the groundwork for his successful presidential campaign the following year. (In 1928, Hoover defeated Democratic presidential candidate Al Smith of New York and his running mate, Joe T. Robinson of Arkansas.) Hoover called the flood “America’s greatest peacetime disaster” and said that “the disaster felt by Arkansas farmers, planters and residents of river lowlands was of epic proportions.”

Amidst the suffering, Hoover saw the opportunity for land reform to change the plantation system which had been in place since Reconstruction. With some large planters bankrupted by the flood, leaving huge tracts of land without effective ownership, Hoover proposed the idea of dividing the land into smaller holdings and building true land ownership for both black and white tenants and sharecroppers. Requesting confidentiality, Hoover issued a memorandum describing the proposal to a few individuals, such as Harvey Couch, flood relief director in Arkansas. Hoover suggested putting aside $1–2 million from flood relief funds. This money would be specifically used for resettlement on twenty-acre farms through a resettlement corporation with directors, including “colored representation.” Nothing came of the plan. When he was elected president, Hoover established private resettlement corporations, all of which were failures.

Through the modern communications of the day, such as radio, the Flood of 1927 drew national attention to the plight of sharecroppers, black and white. It spurred a mass migration of black sharecroppers who had tired of farming, poverty, and debt. Thousands left the plantation as soon as they could, heading north to look for jobs in cities such as Detroit and Chicago. Mechanization and corporate farming replaced their labor. For white sharecroppers and independent small farmers, many family farms in Arkansas, as elsewhere, would come under corporate ownership.

In 1927, the Mississippi River remained at flood stage for a record 153 days. When Arkansans could return to their homes, often in August or September, they began to rebuild. The town of Arkansas City, near McGehee (Desha County), lay beneath the muddy water of the Mississippi and Arkansas rivers from April through August 1927. The Red Cross cared for the entire population of 1,500 people while the town was completely rebuilt.

Arkansas bridges and roads also required extensive rebuilding, and the decision to rebuild the shattered levees led to disagreement among various parties, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who were accused of using outdated manuals.

The Flood of 1927 brought about a political shift, especially among African Americans. Those who had traditionally favored the Republican Party, the party of Lincoln, since the Civil War resented the Republican response, or lack of response, and shifted their allegiance to the Democratic Party.

The 1927 flood also led to a change in attitudes regarding the government’s role in helping its citizens in time of crisis. Prior to this time, people generally feared “the dole” and preferred work to “charity.” However, the enormity of the catastrophe led many to support the type of New Deal programs proposed by Franklin Roosevelt’s Democratic administration in 1932. People now looked to Washington for help, for the misery was not over.

In 1930, just three years later, when many were still recovering, the same rich land that was submerged by floodwater in 1927 turned to dust and blew away in drought. The Red Cross returned and did not conclude its assistance to the Delta until March 15, 1931.

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 has often been compared to the Flood of 1927, which is the tragic benchmark for such natural disasters. In the 1920s, a time when the entire federal budget was around $3 billion, the Flood of 1927 ultimately cost an estimated $1 billion, including damage and indirect costs such as relief, recovery, and lost productivity. Additionally, the 1927 flood had a social and political effect on Arkansas as elsewhere in the affected region, and it remains to be seen if the aftermath of Katrina will have a similar impact.

As in most disasters, the 1927 flood saw the best and the worst of humanity. Of the 1927 flood, author John M. Barry says in Rising Tide: “Their struggle…began as one of man against nature. It became one of man against man. Honor and money collided. White and black collided. Regional and national power structures collided. The collisions shook America.”

For additional information:

“The 1927 Flood.” Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Bobby L. Roberts Library for Arkansas History and Art, Central Arkansas Library System. https://robertslibrary.org/1927flood/ (accessed December 16, 2022).

1927 Flood Exhibit. Delta Cultural Center, Helena-West Helena, Arkansas.

Barry, John M. Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1997.

Bearden, Russell E. “Arkansas’ Worst Disaster: The Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 34 (August 2003): 79–97.

———.“The Great Flood of 1927: A Portfolio of Photography.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 61 (Winter 2002): 388–404.

Daniel, Pete. Deep’n as It Come: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Fatal Flood. American Experience. DVD, VHS. PBS Home Video, 2005.

Hobson, Edythe Simpson. “Twenty-seven Days on the Levee—1927.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Autumn 1980): 210–229.

Lohof, Bruce A., ed. “Herbert Hoover’s Mississippi Valley Land Reform Memorandum.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Summer 1970): 112–118.

Mizelle, Richard M., Jr. Backwater Blues: The Mississippi River Flood of 1927 in the African American Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Parrish, Susan Scott. The Flood Year 1927: A Cultural History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Randolph, Ned. “River Activism: ‘Levees-Only’ and the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.” Media and Communication 6.1 (2018): 43–51.

Sandlin, Jake. “1927 Flood Changed Course of State, U.S.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 16, 2017, pp. 1A, 12A.

Simpson, Ethel C. “Letters from the Flood.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 55 (Autumn 1996): 251–285.

Williams, Michael Vinson. “Steadily Holding Our Heads above Water: The Flood of 1927, White Violence, and Black Resistance to Labor Exploitation in the Mississippi Delta.” In Race, Labor, and Violence in the Delta: Essays to Mark the Centennial of the Elaine Massacre, edited by Michael Pierce and Calvin White. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

Woodruff, Nan. “The Failure of Relief during the Arkansas Drought of 1930–31.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Winter 1980): 301–313.

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

African American Flood Refugees

African American Flood Refugees  Arkansas City Flood

Arkansas City Flood  Baring Cross Bridge; 1927

Baring Cross Bridge; 1927  Clarendon Flood

Clarendon Flood  Clarendon Hotel

Clarendon Hotel  Cotter Flood

Cotter Flood  Dermott 1927 Flood

Dermott 1927 Flood  Dermott 1927 Flood

Dermott 1927 Flood  Dermott Flood

Dermott Flood  Des Arc Flood

Des Arc Flood  Dixie 1927 Flood

Dixie 1927 Flood  Flood Victims

Flood Victims  Fort Smith Flood

Fort Smith Flood  Fulton 1927 Flood

Fulton 1927 Flood  Gillett Flood

Gillett Flood  Guion Flooded

Guion Flooded  Holly Grove Refugees

Holly Grove Refugees  Humphrey Flood

Humphrey Flood  Imboden Flood

Imboden Flood  Lake Village Flood

Lake Village Flood  Lakeport Flood

Lakeport Flood  Marianna Refugees

Marianna Refugees  McGehee after 1927 Flood

McGehee after 1927 Flood  McGehee Flood

McGehee Flood  McGehee Flood

McGehee Flood  Montrose Flood

Montrose Flood  Montrose Flood

Montrose Flood  North Little Rock Flood

North Little Rock Flood  North Little Rock Flood

North Little Rock Flood  North Little Rock Flood

North Little Rock Flood  North Little Rock Flood

North Little Rock Flood  Pine Bluff Flood

Pine Bluff Flood  Plum Bayou Flood

Plum Bayou Flood  Red Cross HQ

Red Cross HQ  Redfield Flood

Redfield Flood  Tupelo Flood

Tupelo Flood  Tyronza Flood Refugees

Tyronza Flood Refugees  White Flood Refugees

White Flood Refugees  White River Flooded

White River Flooded  Yancopin Flood

Yancopin Flood

Though the loss of life toll was drastically different than the Flood of 1927, our community is still impacted by the Flood of 2019. Some houses weren’t rebuilt, this time because the levees didn’t break, they were opened by the City of Little Rock to relieve the strain on it by sacrificing other areas. Now that is shameful.

My grandpa was one year old (his older brother was three, younger sister four months) during the Great Flood when his father (twenty-five years old) and his uncle tried saving a mule from drowning in the river. Both his dad and uncle died, but the mule *survived,* my grandpa would quip. He’d always try to make us laugh despite his incredibly hard life.

Many folk/blues songs mention the suffering and social injustices following the flood and clean-up effort. One that comes to mind is “When the Levee Breaks,” composed and performed by Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe–and covered years later by Bob Dylan, Led Zeppelin, and others. Inclusion of this song in a lesson plan for junior high and high school students might add some interest.

My dad spoke often about the Flood of 1927. He was eighteen and worked in Little Rock. He told me that during that time, he saw housetops, wagons, a few cars from that era, cattle, horses, chickens, and other animals floating down the river. He said that it was an awful and sad sight. The animals would go under a bridge and not be seen on the other side. Some people would try to rescue the animals that were close to the bank, but the river was too swift. He said that cows bellowed the worst and it was very sad and disturbing to him because no one could help them.