calsfoundation@cals.org

New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811-1812

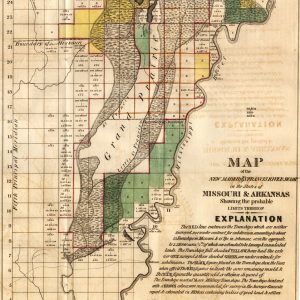

The New Madrid Earthquakes took place between December 1811 and April 1812 along an active fault line that extends roughly from Marked Tree (Poinsett County) in a northeasterly direction, crossing several states for about 150 miles. The earthquakes and aftershocks caused extensive damage throughout northeast Arkansas and southeast Missouri, altering the landscape, affecting settlement of the area, and leaving noticeable reminders that another huge earthquake could happen at any time.

The town of New Madrid, Missouri, on the Mississippi River, was founded by Revolutionary War hero George Morgan in 1789. The town was named by Morgan in an attempt to ingratiate himself and receive a land grant from the King of Spain. Its later pronunciation placed the emphasis on the first syllable of Madrid. New Madrid was a planned community that attracted both permanent settlers and riverboatmen who found it a favored place to stop while traveling on the Mississippi. By 1811, the town had about 400 residents, the largest concentration of people in the area. What is now the state of Arkansas was still part of the Louisiana Territory and more sparsely populated at that time.

On Monday, December 16, 1811, the earth began to shake. Geologists say the epicenter of the huge earthquake was about three miles beneath present-day Blytheville (Mississippi County), though the earthquake was named for New Madrid, Missouri, the only town in the area with a sizeable population. At New Madrid, the people were shaken from their beds at about 2:15 a.m. They poured into the streets in panic, huddling together through the night as animals ran wild, trees toppled over, and houses were leveled. The earth swayed, shook, and gaped open in giant fissures that swallowed anything their path. About 7:15 a.m., just after first light, an even stronger earthquake hit the town.

Thirty miles south, in the river town of what is today Caruthersville, Missouri, all twenty houses were destroyed, and the surrounding land was rendered almost unrecognizable. The ground rolled in several-foot-high waves until they burst, hurling up geysers of water, sand, and a charcoal-like substance. Giant fissures swallowed buildings, along with anyone inside. Some land rose, and other land sank to become inundated with water as rivers changed their course to fill the hollows. Huge chunks of riverbank collapsed into the Mississippi, and an island rose, blocking the current from running downstream. As fissures opened in the riverbed and the banks collapsed, the water was forced to run backward, or upstream, until the temporary island was washed away. Most accounts said it lasted a few minutes, while others said it lasted up to three days.

In Craighead, Mississippi, and Poinsett counties in northeast Arkansas, land near the St. Francis River sank into the earth, creating the “sunken lands” where great forests had stood moments before. In northwest Tennessee, uplifted land dammed Reelfoot Creek as other lands sank, creating Reelfoot Lake, eighteen miles long and five miles wide. In Arkansas, the earthquake created what are now known as Big Lake National Wildlife Refuge in Mississippi County and the St. Francis Sunken Lands Wildlife Management Area in Poinsett County.

Major quakes continued to occur through the winter of 1812. The worst of these came on January 23 and February 7, with about 2,000 tremors and aftershocks continuing into April 1812. Some reports said that between January 23 and February 4, 1812, the earth was in constant motion. The present-day states of Arkansas, Missouri, and Tennessee were the hardest hit, with severe tremors also felt along the East Coast. Church bells in Boston began to ring, and pavement cracked in Charleston, South Carolina. The Indian village of Tuckhabatchee in what is today Alabama was destroyed.

Untold numbers of deaths occurred on the water as riverboats were capsized, wrecked in altered channels, or struck by trees and other debris in the river. While the fatalities on land were reported to be fewer than 100, the actual numbers are not known because of difficulties in accurate reporting such as lack of literacy, delays in communication, and the remoteness of many farms and small communities. Many settlements simply disappeared, such as those along the Mississippi that were lost when the banks collapsed and islands washed away. There has never been an accurate accounting of Native American deaths due to the earthquakes.

Weekly, sometimes daily, tremors continued into 1816. Some who went through the earthquakes thought the end of the world was near. Many settlers in the earthquake zone abandoned what was left of their homes. All but two families left New Madrid, though some eventually returned. Recipients of land grants after serving in the War of 1812 arrived in several areas, such as northeast Arkansas, to find their tracts under water. Settlement in northeast Arkansas was disrupted for decades.

A number of legends have grown around the earthquakes, most notable being a story about the Shawnee chief Tecumseh, who attempted to unify Native American tribes in response to encroachment by white settlers. In September 1811, his efforts were rebuffed at a meeting of southern tribes at Tuckhabatchee. Tecumseh angrily said that, upon returning to his home near present-day Detroit, Michigan, “I will stamp my foot on the ground and shake down every house in Tuckhabatchee.” About the time of his expected return to Detroit, the earthquakes happened.

The fault line continues to be active, with evidence of major earthquakes occurring in the past about every 200–300 years. Small tremors are regularly felt in Arkansas, Missouri, and Tennessee. With millions of people, tall buildings, highways, bridges, electrical lines, gas mains, and other conveniences not known in 1811–1812, one can only speculate at the results of a modern-day New Madrid earthquake.

For additional information:

Feldman, Jay. When the Mississippi Ran Backwards: Empire, Intrigue, Murder and the New Madrid Earthquakes. New York: Free Press, 2005.

Fuller, Myron L. The New Madrid Earthquake. Cape Girardeau, MO: Center for Earthquake Studies, 1989.

Hancock, Jonathan Todd. Convulsed States: Earthquakes, Prophecy, and the Remaking of Early America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021.

The New Madrid Compendium. http://www.ceri.memphis.edu/compendium (accessed April 20, 2022).

Penick, James, Jr. The New Madrid Earthquakes. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1981.

Ross, Margaret. “The New Madrid Earthquake.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Summer 1968): 83–104.

Valencius, Conevery Bolton. “Accounts of the New Madrid Earthquakes: Narratives across Two Centuries of North American Seismology.” Science in Context 25, no. 1 (2012): 17–48.

———. The Lost History of the New Madrid Earthquakes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 New Madrid Fault

New Madrid Fault Big Lake National Wildlife Refuge

Big Lake National Wildlife Refuge  New Madrid Fault

New Madrid Fault  New Madrid/St. Francis River Swamp

New Madrid/St. Francis River Swamp

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.