calsfoundation@cals.org

New Madrid Fault

aka: New Madrid Seismic Zone

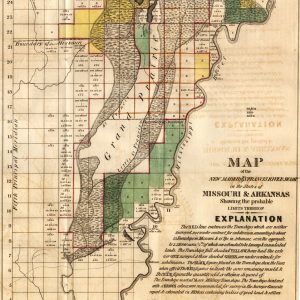

The New Madrid Fault, also called the New Madrid Seismic Zone, is actually a series of faults, or fractures, at a weak spot in the earth’s crust called the Reelfoot Rift. It lies deep in the earth and cannot be seen from the surface. The fault line runs roughly 150 miles from Arkansas into Missouri and Illinois. In 1811–1812, it was responsible for the most violent series of earthquakes in the history of the continental United States (though there have been larger individual earthquakes). Scientists predict that another large earthquake is due which could inflict great damage to Arkansas as well as up to half the nation.

The New Madrid seismic zone runs roughly northeast from Marked Tree (Poinsett County). It generally follows Interstate 55 in a zigzag pattern through Blytheville (Mississippi County), crossing five state lines and cutting across the Mississippi River in three places.

In the winter of 1811–12, a series of powerful earthquakes rocked the Mississippi River Valley. The ground shook so violently that it rang church bells a thousand miles away in Boston. The area around the St. Francis River in northeast Arkansas was the center of the quakes, but since the largest settlement in the area, founded in 1789, was New Madrid, Missouri, with several hundred residents, the seismic zone was called the New Madrid Fault. That earthquake ranks as one of the twenty largest in the history of the world. Today, the New Madrid fault zone, which is active (continuing to move), holds the highest earthquake risk in North America east of the Rocky Mountains. Because of its geologic structure based in sedimentary rock, the damage it can cause is up to twenty times greater than those on the West Coast.

While the fault zones on America’s west coast (such as the San Andreas) are called “transform faults,” those in which the earth’s tectonic plates rub against each other, the New Madrid zone is called an “intraplate zone,” meaning that it is a weak spot in the middle of the North American plate. It is buried deep under sedimentary rock, and its stress is released upwards toward the earth’s surface, rupturing the land and triggering earthquakes when the ground level moves up to thirty feet.

Since the development of the Richter scale to measure the severity of earthquakes, tremors from the New Madrid Fault have regularly appeared on its charts. The New Madrid zone averages about twenty minor events a month, registering at least a 1.0 on the Richter scale. About once a year, there occurs a tremor up to 3.0, and about once every ten years, there is a quake of 5.0 or greater.

A magnitude of over 6.5 means serious damage throughout the region. In 1895, there was an earthquake called the Charleston Quake after the town of Charleston, Missouri, roughly at its center, where the ground sank and a lake was formed. It was magnitude 6.7, which scientists say could be expected to occur about every eighty years and which would cause severe damage to modern cities such as Little Rock (Pulaski County), Memphis, and St. Louis. The Charleston Quake affected northeast Arkansas as well as neighboring states, though the damage was limited to small buildings, such as farm houses, which were the norm of that time, as opposed to the high-rise buildings in today’s crowded cities. As an example of potential damage, the 1994 Northridge, California, earthquake was a magnitude 6.7, and even though it affected a smaller area than the New Madrid zone, it was one of the nation’s costliest earthquakes with over $15 billion in damage.

According to scientists, a New Madrid earthquake measuring over 7.5 on the Richter scale could generally be expected to take place every 200 to 300 years. Such a quake now would trigger destruction in up to twenty states and cause billions of dollars in damage at population centers. The quakes of 1811–12 were comprised of approximately 2,000 tremors, some of which would measure over 8.0 on today’s Richter scale. For several years afterward, there were hundreds of aftershocks. The only reason there was not a catastrophic loss of life from that earthquake was that the area was very sparsely settled. Witnesses reported upheavals so severe that the Mississippi River ran backwards and changed course. Those quakes also formed Tennessee’s Reelfoot Lake by submerging more than ten square miles of land. In addition, huge tracts of land in northeast Arkansas sank into the earth, creating the “sunken lands,” which were uninhabitable for decades. Rich farmland disappeared into the earth or was covered in sand.

Indications of prehistoric “sand blows” lead scientists to suspect major earthquakes in the New Madrid zone around the years 900 and 1450 AD. Seismologists predict a twenty-five to forty percent chance of another major earthquake (6.0 or above) in the New Madrid seismic zone by the year 2040, with great damage and loss of life. The geologic structure of New Madrid fault zone is made of layers of sedimentary rock, such as limestone, which radiates the tremors—much like hitting a bass drum. Because of this “ripple” effect, an earthquake along the New Madrid fault zone would travel farther and cause more damage than a quake of similar magnitude on the West Coast.

National media attention was drawn to the New Madrid seismic zone in 1990 when the late Iben Browning, described as a retired climatologist and business consultant, predicted a fifty-fifty chance of a major quake on December 3, 1990, based upon his theory of lunar pull and tidal patterns. While there was some minor panic as December 3 approached and passed without event, Browning is today credited with bringing increased earthquake awareness and disaster preparation to the region. There is currently a cooperative effort among the U.S. Geological Survey, state governments, and universities such as the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UA Little Rock), the University of Memphis, and St. Louis University to study the hazards, educate the public, and try to minimize risk to people and property from future quakes.

In Arkansas, Earthquake Awareness Week is sponsored by the Arkansas Division of Emergency Management and is held in early February to disseminate earthquake information statewide. Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee formed the Central United States Earthquake Consortium (CUSEC) in 1983 to improve public awareness and education about earthquakes. CUSEC coordinates multi-state planning for earthquake preparedness, response, and recovery, encouraging its member states to adopt stronger building codes to meet modern earthquake design standards.

For additional information:

Afroz, Mahmud. “Modeling the Peak Ground Acceleration and Assessing the Economic Loss and Casualty Due to Potential Earthquakes of Various Magnitudes in the New Madrid Seismic Zone.” MS thesis, University of Arkansas, 2023. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/5129/ (accessed February 21, 2024).

Center for Earthquake Research and Information. http://www.ceri.memphis.edu/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Dougan, Michael B. Arkansas Odyssey: The Saga of Arkansas from Prehistoric Times to Present. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1994.

Dunahue, James Christian. “Paleoliquefaction and Possible Surface Deformations along the New Madrid Seismic Zone in Yarbro, Arkansas.” MS thesis, University of Missouri–Kansas City, 2019.

Feldman, Jay. When the Mississippi Ran Backwards: Empire, Intrigue, Murder, and the New Madrid Earthquakes. New York: Free Press, 2005.

Friedlander, Jay. “Giant in the Earth.” Arkansas Times 12 (October 1985): 53.

Rathgaber, Michelle. “The Archaeology of Mississippian Vulnerability and Resilience in the New Madrid Seismic Zone.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2019. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3326/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Stewart, David, and Ray Knox. The Earthquake That Never Went Away. Gutenberg-Richter Earthquake Series 2. Marble Hill, MO: Gutenberg-Richter Publications, 1993.

Yang, Yang. “A Seismological Study of the Northern Mississippi Embayment.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2020.

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

New Madrid Fault

New Madrid Fault  New Madrid/St. Francis River Swamp

New Madrid/St. Francis River Swamp

My children and I were prepared in 1990, in Forrest City, Arkansas–school canceled, food and water prepared and stored… My children were by my side and slept with me that night. As a teacher, I was trained to administer emergency healthcare (STACKS of newspaper in my classroom for splints, etc.). When nothing happened, many people became complacent about all the preparations “for nothing,” which is quite alarming to me because I do believe such a catastrophic event is likely to happen before many more months/years. It is already “overdue” and people are not ready for it. We watch our wildlife and saw some evidence of something happening on March 28 or 29, 2024, in Garland County, Arkansas. Likely any such “activity” had to do with our area and not widespread, but it made us wonder.