calsfoundation@cals.org

Sunken Lands

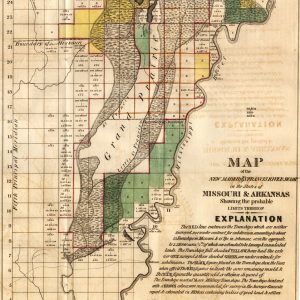

The term “sunken lands” (also called “sunk lands” or “sunk country”) refers to parts of Craighead, Mississippi, and Poinsett counties that shifted and sank during the New Madrid earthquakes which took place between 1811 and 1812. Because the land was submerged under water, claims to property based on riparian rights by large landowners generated controversy which lasted decades and ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court.

When the New Madrid earthquakes began in December 1811, the territory which is today northeastern Arkansas was sparsely populated. An early chronicler described the earthquakes’ effect as the ground moving like waves on the land, when suddenly the earth would burst, sending up huge volumes of water and sand, leaving chasms where the earth had burst open. Huge lakes were created (such as Tennessee’s Reelfoot), and near the St. Francis River in northeast Arkansas, vast tracts of land sank as far as fifty feet into the earth or disappeared into the river.

The quakes continued through March 1812, and land continued to sink in much of today’s Craighead, Mississippi, and Poinsett counties. Those surveying the damage in canoes recorded their shock at seeing forests of tall trees submerged in the murky water with only the tallest branches visible. Lakes replaced hills, and huge fissures filled with stagnant pools. For miles, the quakes caused land to sink beneath the level of the surrounding countryside. The once bountiful northeast Arkansas—filled with verdant forests, abundant game, and fertile ground—became a swamp.

The remoteness of the region, scarcity of settlers, and lack of communication made accurate damage reports impossible for years. Survivors of the quakes took stock of what remained and often abandoned what was left of their homes. Meanwhile, the U.S. government was enticing soldiers into service during the War of 1812 with promises of land grants in the rich areas west of the Mississippi, including northeastern Arkansas.

After the war, veterans and other homesteaders headed west to the Arkansas Territory. Many arrived after surviving the journey and found that their land grant was underwater, habitable only by the snakes and mosquitoes that were rampant. But those who continued farther west were rewarded for their tenacity, encountering the highest point in northeast Arkansas, Crowley’s Ridge, where many chose to stay.

However, for those homesteaders who braved the snake- and mosquito-infested sunken lands out of tenacity or desperation, other battles were just beginning. The land surveys of the area were taken before the earthquakes changed the face of the region, with tracts of arable land now huge lakes bordering on the property owned by large planters. The plantation owners now claimed riparian rights (a real estate term pertaining to ownership of land on the banks of a body of water) for the bordering acreage. Those who wished to develop the area sought to drain the sunken lands for cultivation. The St. Francis Levee District was created by the state of Arkansas in 1893, with large planters in control of the board. Similar drainage districts were organized through the early 1900s in other areas of the disputed land, estimated at between 60,000 and 300,000 acres.

In 1908, the U.S. Department of the Interior announced plans to open the area for homesteading, attracting a number of settlers. Soon, lawsuits disputing ownership of the sunken lands were filed in local, state, and federal courts, and ultimately to the U.S. Supreme Court by large landowner Robert E. Lee Wilson. When there were decisions favorable to small homesteaders, powerful landowners worked to change Arkansas law. In 1921, a federal law was passed to grant large planters “preferential rights” to purchase disputed areas of the sunken lands, and the state legislature enabled their control of the drainage districts. Small farmers were faced with heavy drainage taxes, along with the disastrous Flood of 1927 and Great Depression beginning in 1929. Many lost their land and found themselves in the self-perpetuating sharecropper system, which was entrenched in the region for generations.

Through such innovations as the Marked Tree Siphons, built in 1939, the sunken lands became more habitable. Due to modern drainage techniques, towns in the region have prospered, including Lake City (Craighead County), Turrell (Crittenden County), Lepanto, Marked Tree, Trumann, and Tyronza (all in Poinsett County). A loop off U.S. 63 takes travelers through the region, extending more than thirty miles along the St. Francis River Floodway, an area that has become nationally famous for hunting and fishing as the St. Francis Sunken Lands Wildlife Management Area.

The Marked Tree Siphons are on the National Register of Historic Places and offer a look at flood-control devices throughout the area’s history. Several museums spotlight the history of the sunken lands, including those in Lepanto, Marked Tree, and Trumann.

For additional information:

Dew, Lee A. “The J.L.C. & E.R.R. and the Opening of the ‘Sunk Lands’ in Northeast Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Spring 1968): 22–39.

Whayne, Jeannie M. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor and Federal Favor in Twentieth Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996.

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

Buffalo Island

Buffalo Island Geography and Geology

Geography and Geology Levees and Drainage Districts

Levees and Drainage Districts Big Lake National Wildlife Refuge

Big Lake National Wildlife Refuge  New Madrid/St. Francis River Swamp

New Madrid/St. Francis River Swamp

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.