calsfoundation@cals.org

Flu Epidemic of 1918

aka: Influenza Epidemic of 1918

A deadly influenza outbreak began in 1918 and spread around the world, killing more people than any other outbreak of disease in human history. In Arkansas, the flu killed about 7,000 people, several times more than the state lost during World War I. This flu’s history remains significant today as world health officials seek to prevent an outbreak of a similar influenza epidemic mutated from swine or “bird flu” from poultry.

In the fourteenth century, Italian doctors noted a mysterious illness that often turned into an epidemic. They called it the influentia in medieval Latin, believing it was caused by an adverse influence of the stars or alignment of the planets. By the eighteenth century, it was called influenza di freddo, or “influence of the cold,” as Italian doctors thought it might be caused by a chill. French doctors called it la grippe (from the word “seize” or “grasp,” as the illness tenaciously gripped its victims). The disease was very quick, very contagious, and had the ability to mutate into different strains, so treatment for one strain might not work for another. Modern researchers have also discovered the flu’s ability to mutate from animals to humans.

Scientists theorize that the 1918 strain may have begun in rural Haskell County, Kansas, where people lived close to their pigs and poultry. With the entry of the United States into World War I on April 6, 1917, men were drafted and sent to large training camps before being transported to Europe. In February 1918, after visiting their families in Haskell (where there were reports of people dying from severe flu) several soldiers on leave reported back to duty at Camp Funston, part of the Fort Riley complex in eastern Kansas.

In early March 1918, a soldier at Camp Funston went on sick call complaining of headache, sore throat, muscle aches, chills, and fever. By noon, more than a hundred men joined him. Within a month, 1,000 were sick, and almost fifty soldiers were dead. They were strong, healthy young men whose lungs filled with fluid so quickly they drowned, sometimes within twelve hours of feeling sick. Because the lack of oxygen in the blood seemed to turn the victims dark blue, purple, or black, comparisons were drawn to the “Black Death” (most likely bubonic plague) of the Middle Ages. The 1918 flu would go on to kill more people in one year than the Black Death did in a century.

Conditions in 1918 were perfect for spreading the disease as civilian war workers moved around the country, draftees were sent to overcrowded training camps, and soldiers were shipped off to war in the cramped, stuffy holds of troop ships, which became known as “floating caskets.” Influenza spread to American cities and rural areas alike, as well as to the battlefields of France before spreading throughout Europe. It killed eight million Spaniards with terrible speed. Because the press in Spain, a neutral country, was not censored into ignoring the epidemic as combatant countries did (for fear of lowering morale), it became known as the Spanish Flu.

In Arkansas, the flu ultimately killed more than 7,000 people. It may also have had more far-reaching consequences: the port city of Brest in France, where almost half of all U.S. soldiers disembarked, had survived an epidemic of a milder flu strain earlier in 1918, but as John M. Barry states, “the first outbreak with high mortality occurred in July, in a replacement detachment of American troops from Camp Pike, Arkansas.”

Camp Pike (renamed Camp Robinson in 1937) in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) was established in 1917 for army basic training. While about eighty percent of Arkansans lived on farms in 1918, Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and the nearby Little Rock (Pulaski County) area each had more than 30,000 residents. With 52,000 men at Camp Pike, its infirmary began admitting up to a thousand men a day. The camp was sealed and quarantined, and the commandant ordered that the names of the dead not be released to the press. Still, more than 500 civilian cases soon appeared in the Little Rock area. J. C. Geiger, U.S. Public Health Service officer for Arkansas, downplayed the threat to the state with reassuring statements (possibly to avert a panic), even after he caught the flu and his wife died of it. Arkansas officials did little to prepare for the epidemic, partly based on Geiger’s reassurances and the lack of press coverage in wartime.

The disease spread to rural areas of Arkansas, where many deaths likely went unreported. It cannot be determined how many rural residents died because of several factors: lack of medical care in isolated areas, no telephones or other means of communication, lack of literacy skills to record the deaths, and no cemetery records, since many were buried in unmarked graves in family burial grounds. Sometimes entire families, too weak to draw water or cook their own food, died of the disease, thirst, or starvation. Country people, who were known for helping each other during illnesses, generally could not or would not help their neighbors in 1918 either from being too sick themselves or out of fear.

Race was also a factor in the high death rate. In response to pleas from Arkansas and elsewhere, one national medical publication stated, “No colored physicians available.” It was noted nationwide that there seemed to be a higher mortality rate among African Americans than whites, possibly because of a lack of medical care. The actual numbers probably went unrecorded in Arkansas as well as overseas, where one report stated that “a considerable number of American negroes…have contracted Spanish influenza and died in French hospitals.” It is not known how many a “considerable number” of the nameless dead might be. Nor is it known how many black sharecroppers on Arkansas plantations went untreated or died unrecorded. People with the best chance of survival were those who took to bed soon after the first symptoms, stayed in bed for several weeks, and had the best care. Across the nation, the poor died in larger numbers than the rich, and Arkansas was probably no exception.

In Arkansas, many voters were too sick or afraid to go out on the rainy election day of 1918. The proposed state constitution, which contained provisions for women’s suffrage and prohibition of alcohol, was defeated in part because of low voter turnout, though informal surveys before election day are inconclusive as to whether the constitution might have passed otherwise.

When the state confirmed 1,800 cases of influenza in October 1918, the Arkansas Board of Health put the state under quarantine, despite Geiger’s continued reassurances (“Situation still well in hand”) and helpful hints (“Cover up each cough and sneeze; if you don’t you’ll spread disease”). Pulaski County lifted the quarantine on November 4, 1918, with county boards of health responsible for lifting restrictions in rural areas, though public schools remained closed statewide, and Arkansas children under eighteen were confined to their homes for another month.

After the war ended on November 11, 1918, there was more press attention to the epidemic. Arkansas remained in the grips of influenza through much of 1919, though the death rate began to drop, except in rural areas, where more new cases were reported in south Arkansas beginning in late November 1918.

By the time it ended in 1919, the flu claimed at least 675,000 Americans. About 7,000 Arkansas deaths were recorded, out of the state’s population of roughly 1,700,000, though the exact number of deaths, especially among blacks and in rural areas, may never be known. It is believed that the number of deaths worldwide could be as high as fifty to a hundred million, with an unusually high incidence of death in healthy young adults.

The epidemic disappeared almost as suddenly as it struck. Milder types of influenza have followed, such as “swine flu” and the Asian and Hong Kong varieties, challenging medical science to treat each new form. Today, science confronts the avian flu, since there is evidence that the 1918 began in poultry and/or pigs. In Arkansas as elsewhere, with better communication and lack of media censorship for “patriotic” reasons, as there was during World War I, life-saving information might be disseminated more effectively.

For additional information:

“1918.” Arkansas Times 12 (June 1986): 73.

Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. New York: Viking, 2004.

Getz, David. Purple Death: The Mysterious Flu of 1918. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2000.

DeBlack, Thomas A. “Epidemic!: The Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918 and Its Legacy in Arkansas.” In The War at Home: Perspectives on the Arkansas Experience during World War I. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Hendricks, Nancy. “PLAGUE!: The 1918 Influenza Epidemic in Arkansas.” In To Can the Kaiser: Arkansas and the Great War, edited by Michael D. Polston and Guy Lancaster. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2015.

Hogan, J. B. “Fayetteville and the Influenza Epidemic of 1918.” Flashback 71 (Fall 2021): 106–119.

Influenza Encyclopedia. https://www.influenzaarchive.org/ (accessed July 20, 2020).

Jarvis, Lauren. “In the Grippe of Influenza: Arkansas and the Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1918.” Arkansas Military History Journal 14 (Winter 2020): 4–9.

Kolata, Gina. Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus That Caused It. New York: Touchstone, 2001.

Nutt, Tim. “1918: A Different Pandemic.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 21, 2020, pp. 1D, 6D.

Prewitt, Taylor. “When the Flu Hit Fort Smith.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 43 (September 2019): 14–22.

Scott, Kim Allen. “Plague on the Homefront: Arkansas and the Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Winter 1988): 311–344.

Taggart, Sam. “The Deadliest Month: The Spanish Flu of 1918 in Rural Arkansas.” The Saline 33 (Spring 2018): 18–27.

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

Leon Kendall Bostwick, Flu Victim

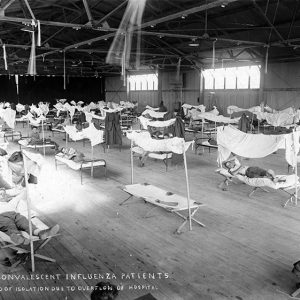

Leon Kendall Bostwick, Flu Victim  Flu Patients

Flu Patients

(Told to James R. Teeter by his mother, Neva Taylor Teeter of Conway, Ark., on July 17, 2001, three years before her death at age 94.) In 1918, almost everybody who lived in the small community of Center Valley adored baby James Taylor, nearly one. That is, until the flu pandemic of 1918 began to sweep the world, eventually spreading to the entire Taylor household. James soon developed pneumonia. With most members of the family sick, Aunt Velma Parker (sister of Jamess mother) came from Russellville to help. When Neva (then eight) and her older brothers Roy and Earl walked into the kitchen one morning, Velma was crying inconsolably. Hes gone, honey, Velma said to Earl. The babys death was devastating. Jamess mother was so despondent and sick with the flu (she almost died that week) that Jamess funeral service was held at her bedside. At the time of Jamess death, the weather was wet and cold, and roads were in terrible condition. Nobody thought Mr. Nugent, the undertaker in Russellville, could get to Center Valley with a casket and his burial coach (hearse). But he pulled up to the house in his horse-drawn coach to take the casket to Old Baptist Cemetery. Before leaving for the cemetery, Neva told her father that she had some nickels and dimes that she wanted to put in the casket in case James should ever need to buy something. Her father watched as she placed her monetary wealth in the casket beside James. Nevas grandfather, who seemed to be taking Jamess death harder than anybody else, had loaded hay into the back of his buggy. When he tossed the hay on top of the casket, people asked why he had done this. He replied, I cant stand hearing the sound of dirt hitting our sweet baby.