calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium

The Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium (also called simply the State Sanatorium) was established in 1909 about three miles south of Booneville (Logan County). Once fully established, the sanatorium was a hospital for the treatment of white Arkansans with tuberculosis. By the time the facility was closed in 1973, it treated over 70,000 patients, and in time, its main hospital, the Nyberg Building, became known worldwide for its tuberculosis treatment.

With the passage of Act 378 of the Arkansas General Assembly, a board of trustees was created to oversee the search for land to build a sanatorium. This was a very vital start to create a facility that would, in fact, quarantine a highly pathogenic disease. Tuberculosis, which caused scarring of the lungs and led to many deaths, was spread by the fluids of the respiratory tracts of infected persons; the bacteria that caused it could become airborne when those fluids dried. Before the sanatorium, the mortality rate of the disease was eighty percent. The sanatorium helped to reduce that rate to ten percent.

The search for land began in March 1909, and the site south of Booneville was selected by October. The first patient was admitted in August 1910; by year’s end, the population at the center had reached sixty-four. In 1924, the Belle Pointe Masonic Lodge in Fort Smith (Sebastian County) constructed the Mason’s Building for children, and in 1927, a school was added for the young patients.

In 1938, the legislature passed the Nichols-Nyberg Act, which funded the construction of a new hospital building on the grounds. The act was promoted by Phillips County Representative Leo E. Nyberg, who had tuberculosis and lived at the sanatorium, and by Logan County Representative Lee Nichols. The hospital building, probably the most notable on the grounds, is 528 feet long and five stories tall with a full basement and housed 511 patients. The building also housed doctors’ offices, X-ray facilities, and the employee cafeteria and kitchen, and while it was not common knowledge, the sanatorium morgue was housed there also. The building was named for Nyberg, although he passed away before it was completed in 1941. The facility became known worldwide for tuberculosis treatment as it was one of the most modern and successful facilities of the day. Today, half of the first floor is used for offices, and the rest of the building is closed.

Besides the Nyberg Building, the facility had many structures, including dormitories, staff entertainment buildings, a chapel, a laundry, water treatment plant, and even a fire department. Today, most of the structures are used, and in fact, the fire department still operates within the grounds, and until recently, the Benedictine monks of Subiaco Abbey and Academy operated the chapel. The complex was self-sustaining, housing nearly 300 staff members at the height of its use, and the total population of the center at the time was greater than that of Booneville in the valley below.

In the 1950s, new drugs to treat tuberculosis had resulted in a decline in the center’s patient population. In addition, Dr. Joseph Bates of the Veterans Administration Hospital in Little Rock (Pulaski County) had been conducting research into tuberculosis and, with his colleagues, was able to prove that, with proper treatment, a patient with tuberculosis would be communicable for only two weeks, rather than many months. In 1970, he testified before the Arkansas Legislative Council that treatment at hospitals should be prioritized.

It was decided by the sanatorium administration to operate it as a children’s hospital as well; this continued until the facility closed in 1973. In 1971, the Arkansas General Assembly dissolved the sanatorium as an independent agency and created the Department of Health to oversee it. At the time, the health department was also left in charge of the sanatorium at Alexander (Pulaski and Saline Counties), which was the relocation center for all non-white people with tuberculosis.

On February 26, 1973, the last seven patients were discharged, and on March 13, the legislature approved Act 320, authorizing the facility’s closure and the transfer of control from the Department of Health to the Board of Mental Retardation. On June 30, 1973, the Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium officially closed, and the main gates were left unlocked for the first time in more than sixty years. Today, the facility operates as the Booneville Human Development Center and is classified as a historic site.

While most people who were condemned to live at the center considered it the equivalent of a death sentence, in actuality, the outdoor air on the top of the mountain benefited patients. Treatment—consisting of fresh air, bed rest, and drug therapy—usually lasted from ten months to two years, although some people did stay longer.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium Historic District.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/arkansas-historic-preservation-program (accessed February 7, 2023).

Floyd, Larry C., and Joseph H. Bates. Stalking the Great Killer: Arkansas’s Long War on Tuberculosis. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2023.

Koon, David. “‘Every Day Was a Tuesday.” Arkansas Times, June 17, 2010, pp. 10–15. Online at https://arktimes.com/news/cover-stories/2010/06/17/every-day-was-a-tuesday (accessed February 7, 2023).

Martin, Amelia. “Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium Wildcat Annex.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 21 (September 1997): 12–14.

Petersen, Svend. “Arkansas State Tuberculosis Sanatorium: The Nation’s Largest.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 5 (Winter 1946): 312–329.

Taggart, Sam. The Public’s Health: A Narrative History of Health and Disease in Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Times, 2014.

William Tyrell Leeper

Waldron, Arkansas

Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium

Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium  Administration Office

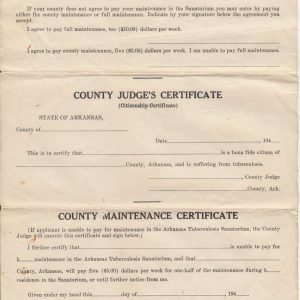

Administration Office  Sanatorium Applicant's Certificate

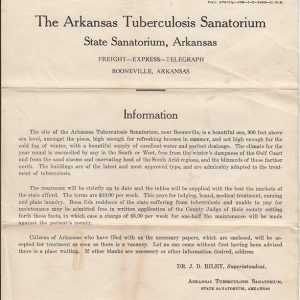

Sanatorium Applicant's Certificate  Sanatorium Flyer

Sanatorium Flyer  Tuberculosis Sanatorium Chapel

Tuberculosis Sanatorium Chapel  Tuberculosis Ward

Tuberculosis Ward

The ATS did not incarcerate individuals. It was not a prison; it was a hospital. If someone tested negative for tuberculosis, they were not admitted. Individuals with mental conditions were sent to the Arkansas State Hospital.

My mother from Rector, Arkansas, was in Booneville. I’d like to find out more about her stay there.

Sanatorium Hill is a documentary about the lives of patients at the institution. It was made in 2001 by Larry Foley and Dale Carpenter of the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville journalism department. It was broadcast on AETN.

My mother, Aleene Lawler Coker, of Hot Springs, Arkansas, was a registered nurse with a new baby at home when she was wrongly incarcerated at the sanatorium. My mother knew that she did not have tuberculosis and told the authorities that she had tested negative and to please let her stay home and take care of her new baby (me) and my daddy who was dying at the time. I am now 53 years old. At the time my mother was finally released, my daddys health had declined and I became a 4-year-old caregiver of two critically ill parents! My father died shortly thereafter; he was the ONLY parent I had ever known. Now I was left to care for my ill mother, who lost her mind at Booneville. There was no care or concern for those of us who were left behind.

My mother and dad both were in this hospital. They met there and got married. There names are Loyd Calley Morgan and Dorothy Ellen Pillow–both were from the east side of Arkansas. Mom lived to be 92 (died of natural causes). Dad died with heart trouble.