calsfoundation@cals.org

Separate Coach Law of 1891

The Separate Coach Law of 1891 (Act 17) was a Jim Crow law requiring separate coaches on railway trains for white and black passengers. The law arose out of the political upheavals of the era, in which the Democratic Party sought to stave off challenges to their dominance by distracting voters with racist concerns, and it further relegated African Americans to the margins of social and economic life.

By the late 1880s, large numbers of angry white farmers threatened to leave the Democratic Party and join new agrarian parties, such as the Union Labor and Populist organizations. Democratic chieftains and established elites tried to allay defections and distract attention from economic and class issues that were beginning to divide the white vote by stoking racial flames.One method of doing so was to call for enactment of “Jim Crow” laws mandating racial segregation. Responding to a resolution adopted in 1890 at the state Democratic convention, as soon as the legislature convened in January 1891, lawmakers introduced bills requiring racially separate passenger coaches on railway trains and waiting rooms in train stations. Party leaders endorsed a proposal by Senator John N. Tillman of Washington County that required railroads to maintain “equal but separate and sufficient” passenger coaches and waiting rooms.

Small companies operating roads less than twenty-five miles long could conform by dividing coaches with a partition; street railways were exempt. Other features not directly related to race were an order for the railroads to provide drinking water at stations and on passenger trains, and a fine for using profane language. Failure to comply would cost companies $100 to $500. The law charged railroad officers with enforcement, on pain of a twenty-five- to fifty-dollar penalty. Passengers refusing to follow the officers’ directions could be fined ten dollars to two hundred dollars.

Proponents said similar legislation in other Southern states had been sustained in court. Legal scholar Charles A. Lorgren has insisted that federal court decisions did not trigger the first wave of separate-coach legislation in the late nineteenth century, but evidence suggests that they were a significant factor in engendering Arkansas’s law. On the Senate floor, Tillman said his bill was “modeled after the Mississippi statute,” which, he noted, had “been tested in the courts and pronounced constitutional.” The statement no doubt alluded to the 1890 case of Louisville, New Orleans, and Texas Railway v. Mississippi, in which the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Mississippi separate-coach law did not impose an undue burden on interstate commerce. In Arkansas, it was mistakenly assumed that the decision had given judicial sanction to the separate-but-equal doctrine.

An initial protest meeting was held January 19, 1891, at the black First Baptist Church in Little Rock (Pulaski County), and more than 600 people attended. A special committee of recognized race leaders—John E. Bush, cofounder of the Mosaic Templars of America; George N. Perkins, an attorney and former city councilman; W. H. Scott, a landowner and former city councilman; Y. B. Sims, pastor of the black First Congregationalist Church; and J. H. Smith, a Little Rock dentist—presented several forceful resolutions, all of which passed unanimously. The resolutions denounced the separate-coach proposal as caste legislation, warned that attempts to determine an individual’s race could lead to embarrassing mistakes, and predicted that segregation would invite rudeness and incivility.

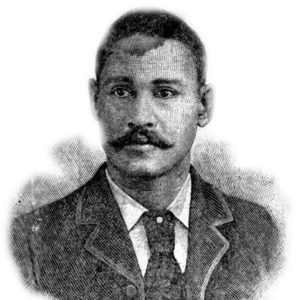

A second protest meeting, held January 27 and chaired by Perkins, met in the House of Representatives chamber of the State House. An estimated 400 black citizens and a few whites attended. The crowd heard four black leaders express disapproval of Tillman’s bill: Joseph A. Booker, president of Arkansas Baptist College; Smith; and two ministers, Asberry Whitman and H. T. Johnson.

Booker attacked the proposal on the grounds that it assumed all black people were alike, that it would shut off blacks from white people and their example, and that it would not produce equal accommodations for black people on the railroads but only result in “race humiliation.” He asked that the legislature require the railroads to offer first- and second-class service open to both races on the basis of ability to pay.

Smith and Whitman’s arguments were similar to Booker’s. Johnson’s speech was not summarized; the Arkansas Gazette reported that it was “characterized throughout by conservatism and eloquence.”

Almost all the black members of the legislature vigorously fought the separate-coach bill. In the Senate, the burden of opposition fell on the only black member, Republican George W. Bell of Desha County. Initial debate occurred on January 29 before a packed audience in the galleries, in a dramatic exchange between Tillman and Bell. Answering Tillman’s appeal for passage of his bill, Bell denied the need for separate coaches stating: “The negroes have been riding upon and within the same coaches, in common with all other races, in this state for more than eighteen years” without serious trouble. Bell concluded with an appeal for good will between African Americans and whites, and pictured the advent of a new dawn in the South.

His moving oratory may have upset the stereotypes of many whites at the Senate debates, but their surprise was probably nothing compared to the shock of those who listened to the militancy of the chief black spokesman in the House, John Gray Lucas of Jefferson County. After receiving a law degree from Boston University in 1887, Lucas had returned to Arkansas and won appointment as U.S. commissioner for the state’s Eastern Federal Judicial District. In 1891, he was serving what would be his only term in the legislature. Lucas spoke before his fellow lawmakers on February 17. He believed that the social philosophy of the bill’s sponsors was contrary to the most advanced Western thought and that segregation went against the grain of the fundamental American principle of personal liberty.

The final legislative tally showed that the bill enjoyed insurmountable support. In the Senate, it carried by a vote of twenty-six to two, with only Bell and a white Union Laborite, F. P. Hill, voting against it. The Senate even adopted an amendment, over the objections of the bill’s author and the sponsoring committee, that prohibited black nurses from riding in the same railway car with their white charges and employers.

By the time the bill went before the House, it was apparent it would pass. The House nevertheless rejected a proposed amendment that would have extended coverage to streetcar lines, probably because of the influence of urban business interests.

In the House, the bill passed seventy-two to twelve. Only two white House members voted against passage: William A. Carlton of Newton County and J. F. Henley of Searcy County, both mountain Republicans. By contrast, of the eleven black House members, only the sole black Democrat, Benjamin F. Adair of Pulaski County, voted for passage.

Adoption of the separate-coach law was a watershed development in Arkansas race relations. Paradoxically, though the device of separate coaches was new, the purpose of the law was to preserve the old: to renew the ancient distinctions of caste, which were already beginning to decay in the cities and towns. Despite well-organized black resistance, Arkansas began a journey into the past. For Arkansas’s black citizens, the mournful cries of the train whistles in 1891 were both reminders of time gone before and omens of things to come.

Once enacted, the separate-coach law would remain on the statute books for the next eighty-two years. In 1955, however, the Federal Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) decreed that all racial segregation on interstate passenger trains and buses must end by January 10, 1956. The ICC ruling also applied to waiting rooms in railway and bus stations. Since almost all railway passenger service in Arkansas at the time involved interstate transit, the ruling had an immediate and sweeping impact. The practical collapse of the old Jim Crow system led finally to the repeal of the 1891 separate-coach law through the enactment of Act 253 (section 5) of the Arkansas General Assembly in 1973.

For additional information:

Graves, John William. “The Arkansas Separate Coach Law of 1891.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Summer 1973): 148–165.

———. “The Arkansas Separate Coach Law of 1891.” Journal of the West 7 (October 1968): 531–541.

———. “Jim Crow in Arkansas: A Reconsideration of Urban Race Relations in the Post-Reconstruction South.” Journal of Southern History 55 (August 1989): 421–448.

———. Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban-Rural Context, Arkansas, 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Kousser, J. Morgan, ed. “A Black Protest in the ‘Era of Accommodation’: Documents.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 34 (Summer 1975): 149–175.

John William Graves

Henderson State University

Joseph A. Booker

Joseph A. Booker  John Bush

John Bush  John Gray Lucas

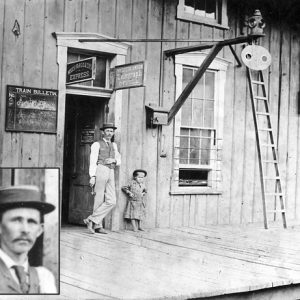

John Gray Lucas  Segregated Waiting Room

Segregated Waiting Room  Segregated Waiting Room Door

Segregated Waiting Room Door

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.