calsfoundation@cals.org

Ku Klux Klan (Reconstruction)

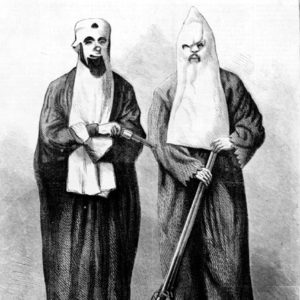

The Reconstruction era in Arkansas witnessed the first of many incarnations of the state’s most well-known white supremacist organization, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). In the years after the Civil War, African Americans not only had to struggle to achieve equality under the law, but—along with their white supporters—they had to endure intimidation, whippings, shootings, and murders. Although much of the racial violence was random, it was also during this time that the KKK began its long history of using violence to achieve political ends.

The Ku Klux Klan first appeared in Arkansas in April 1868, just a month after African Americans voted in Arkansas elections for the first time. A year earlier, Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts, which put Arkansas under federal military supervision and required the state to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment and adopt a new state constitution that included black suffrage. Because ex-Confederates were not allowed to vote or hold office, many white people (who tended to be Democrats) were excluded from the ratification process and the formation of a new state government. In the March general election, Arkansas voters approved a state constitution, and Republican candidates won the governor’s office and eighty-two of eighty-three seats in the legislature. On April 2, the legislature ratified the Fourteenth Amendment.

With the new constitution, the Republican-dominated government, and the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Democratic-controlled government of 1866 and 1867 was displaced. In response to this political upheaval—particularly the guaranteed suffrage of African-American men and the disfranchisement of ex-Confederate Democrats—the Ku Klux Klan soon surfaced and began terrorizing the state’s freedmen and their supporters, as it had in other Southern states. Threatening KKK flyers appeared on the street corners of Little Rock (Pulaski County) in April 1868, and the Klan’s presence quickly spread across the state.

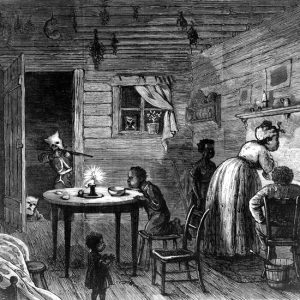

Klan members terrorized members of the black community by whipping, beating, and intimidating them, by taking their guns, and by breaking up their religious gatherings. The Klan also attacked Freedmen’s Bureau agents, military officials, state legislators, and other white people associated with the Republican Party or the protection of African Americans. One of the most notable acts of violence occurred when U.S. Representative James Hinds was assassinated and state Representative Joseph Brooks was seriously wounded in Monroe County.

The KKK’s violence and intimidation reached their peak in the months leading to the November 1868 general election. The Klan used violence to try to disrupt voter registration and intimidate prospective Republican voters. In the three months before the election, the governor’s office received reports of more than 200 murders.

After the election, Republican Governor Powell Clayton acted aggressively to address the threat from the KKK. In his November 24 address to the General Assembly, Clayton said that the “reign of terror” being inaugurated threatened to “obliterate all the old landmarks of justice and freedom and to bear us onward to anarchy and destruction.” Clayton declared martial law in ten counties that he deemed to be in a “state of insurrection.” Over the summer, he had raised a militia of Union sympathizers and former slaves, giving Arkansas the most active black militia movement of any Southern state. The militia quickly moved into the ten counties under martial law, as well as other troubled counties.

Over the next three months, the state witnessed major clashes between the militia and the Ku Klux Klan in places such as Woodruff, Conway, Craighead, Greene, Fulton, and Mississippi counties. The militia was successful as it fought, arrested, disarmed, and killed Klan members, and hundreds of remaining Klan members began fleeing to Tennessee and other surrounding states. Because of this quick success, by February 6, 1869 martial law was lifted in all counties except Crittenden, where it was lifted the first week in March.

Soon, order was restored throughout the state, and on March 13, 1869, the General Assembly passed a law that made the Ku Klux Klan illegal. With the militia, Clayton accomplished more than any other Southern governor in suppressing the Klan’s activities, and the organization virtually ceased to exist in Arkansas throughout the rest of Reconstruction.

For additional information:

Blevins, Brooks. “Reconstruction in the Ozarks: Simpson Mason, William Monks, and the War That Refused to End.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 77 (Autumn 2018): 175–207.

Finley, Randy. From Slavery to Uncertain Freedom: The Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas, 1865–68. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Moneyhon, Carl. The Impact of Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

Trelease, Allen W. White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971.

Brian D. Greer

Washington DC

Dollar, William, and "Fed" Reeves (Murders of)

Dollar, William, and "Fed" Reeves (Murders of) Humphries, Ban, and Albert H. Parker (Murders of)

Humphries, Ban, and Albert H. Parker (Murders of) Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan  Ku Klux Klansmen

Ku Klux Klansmen

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.