calsfoundation@cals.org

Trail of Tears

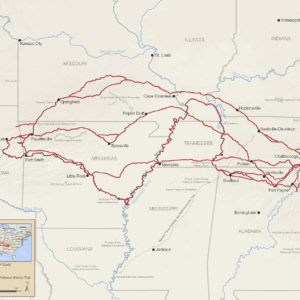

“Trail of Tears” has come to describe the journey of Native Americans forced to leave their ancestral homes in the Southeast and move to the new Indian Territory defined as “west of Arkansas,” in present-day Oklahoma. Through coerced or fraudulent treaties, Indians had been given the choice of submitting to state jurisdiction as individuals or moving west to preserve their sovereign tribal governments. The metaphoric trail is not one distinct road, but a web of routes and rivers traveled in the 1830s by organized tribal groups from Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Tennessee. All of these trails passed through Arkansas.

During the decade after passage of the federal Indian Removal Act in 1830, an estimated 60,000 Indians, African slaves, white spouses, and Christian missionaries traveled through Arkansas. The estimate includes 21,000 Creek (whose descendents prefer to be called Muscogee), 16,000 Cherokee, 12,500 Choctaw, 6,000 Chickasaw, 4,200 Florida Indians now collectively identified as Seminole, and an unknown number of emigrants from various smaller tribes.

They traveled upriver on contracted steamboats and along primitive roads. Large caravans and small independent groups rode west with wagonloads of possessions, herds of horses. Others walked barefoot, wearing thin, ragged clothes. Weather was often a fateful factor as Arkansas experienced some of its coldest winters and driest summers during that decade. Supplies of food, fodder, and firewood were arranged along the way by the military, private contractors, or tribal leaders. Even with physicians assigned to most removal groups, many died from infectious diseases such as cholera, dysentery, measles, and smallpox. No one knows how many are buried on the trail or even exactly how many survived.

The description “Trail of Tears” is thought to have originated with the Choctaw, the first of the major Southeast tribes to be relocated, starting in 1830. But it is most popularly connected with the October 1838 to March 1839 journey organized by the Cherokee Nation. In that tribe’s language, the trek is known as nunahi-duna-dlo-hilu-i—“the trail where they cried.”

The majority of Cherokee had been fighting removal in court and in Congress trying to overturn an 1835 treaty signed by a small, unauthorized group. But when the Georgia Guard rounded up families after the May 1838 treaty deadline, and after federal authorities began transporting Cherokee Indians west on steamboat, tribal leaders conceded defeat and asked that the Cherokee Nation be allowed to supervise its own removal.

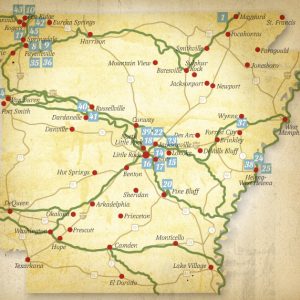

Thirteen overland detachments of about 1,000 Cherokee each were assembled. Most of these wagon trains are thought to have followed similar routes across northwest Arkansas, entering the state just east Pea Ridge (Benton County) and then veering west near Fayetteville (Washington County). In 1987, Congress recognized this so-called Northern Route of the Cherokee as the land route of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. Signs designating the Auto Tour Route of the national trail are posted along highways in Benton and Washington counties. One Cherokee Nation detachment of about 1,200, led by John Benge, is known to have followed a separate route across north-central Arkansas, entering at the Current River in Randolph County, repairing wagons at Batesville (Independence County), and passing through Fayetteville. A separate pro-treaty group of about 660, led by John Bell, traversed the state on the military roads connecting Memphis, Little Rock (Pulaski County), and Fort Smith (Sebastian County).

Principal Chief John Ross with the final Cherokee Nation detachment of about 228 took the water route commemorated by the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail—along the Tennessee, Ohio, Mississippi, and Arkansas rivers. His wife, Elizabeth (or Quatie), died aboard the Cherokee-owned steamboat Victoria shortly before reaching Little Rock, where she was buried.

Unlike the Northern Route, which is solely Cherokee, the Arkansas River segment of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail was traveled by other exiled Indians, including the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole.

North Little Rock (Pulaski County)—then merely the opposite side of the Arkansas River from Little Rock—was state’s most active site during Indian Removal. Detachments of Choctaw, Muscogee, Chickasaw, and Cherokee arrived overland on the Memphis to Little Rock Road. Choctaw and Chickasaw were ferried across the river to proceed down the Southwest Trail. Others continued overland north of the river on the military road to Fort Gibson or south of the river to Fort Coffee, both in Indian Territory. Florida Indians captured during what came to be known as the Second Seminole War moved through Arkansas mostly by water.

Many detachments traveled a combination of land and water routes. Steamboat passengers stranded by low water on the Arkansas River often had to finish the journey on foot if they could not hire wagons. Other removal routes begun on water and completed overland were on the White River to Rock Roe (Monroe County) and the Ouachita River to Camden (Ouachita County).

The movement of large groups of Indians through sparsely populated Arkansas incited fear and greed. For the most part, detachment leaders tried to keep the emigrants and the residents separated and especially keep whiskey peddlers and gamblers out of the Indian encampments. Suppliers were often accused of price-gouging. Indians were accused of raiding corn fields and burning fence rails as firewood. Both groups accused the other of stealing horses. At one point, Governor James Conway called out the militia because a detachment of Muscogee was not moving fast enough to suit him.

New research is helping to pinpoint the locations, the events, and the impact of the Trail of Tears in Arkansas. Identifying routes is sometimes a matter of identifying what roads would have been wagon-worthy. Maps, newspaper reports, diaries, and government documents such as ferry receipts have helped. But still there are many unanswered questions.

The Trail of Tears Association (TOTA), a nine-state volunteer network of institutions and individuals, is headquartered in Little Rock. As a support group for the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, TOTA helps the National Park Service with research and interpretation. The Sequoyah Research Center at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) has amassed a unique collection of government removal documents from the National Archives. The Department of Arkansas Heritage and its Arkansas Historic Preservation Program have used old maps and modern technology to locate surviving road segments and add them to the National Register of Historic Places.

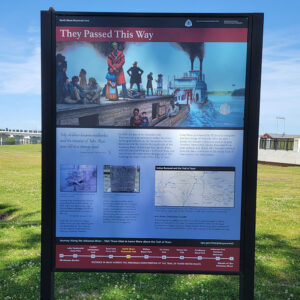

Perhaps the earliest marker recognizing a route of the Trail of Tears was placed at Marion (Crittenden County) in 1931. Other vintage markers are at Colt (St. Francis County), De Queen (Sevier County), Fayetteville, and Springdale (Washington County). Recent interpretive markers have been placed at Helena (Phillips County), North Little Rock, Cadron (Faulkner County), Russellville (Pope County), Fort Smith, Pea Ridge National Military Park, and Village Creek State Park, with more likely to be placed in the future.

For additional information:

Duffield, Lathel F. “Cherokee Emigration: Reconstructing Reality.” The Chronicles of Oklahoma 80 (Fall 2002): 314–347.

Foreman, Grant. Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1972.

<Inskeep, Steve. Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab. New York: Penguin, 2015.

Journey of Survival: Indian Removal through Arkansas. http://www.journeyofsurvival.org/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Musick, Pat, with Jerry Carr and Bill Woodiel. Stone Songs on the Trail of Tears: The Journey of an Installation. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

Sequoyah Research Center. University of Arkansas at Little Rock. http://ualr.edu/sequoyah/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. http://www.nps.gov/trte (accessed July 28, 2023).

Kitty Sloan

Arkansas chapter, Trail of Tears Association

Dover to Clarksville Road

Dover to Clarksville Road  Trail of Tears

Trail of Tears  Trail of Tears Map

Trail of Tears Map  Trail of Tears Marker

Trail of Tears Marker  Trail of Tears Sign

Trail of Tears Sign

Thank you for the great information regarding the Trail of Tears. I have spent a lot of time along the Arkansas River, particularly in North Little Rock below the Big Dam Bridge. I was aware the trail had history here but knew little of the facts. For the last month and a half, much of my spare time was spent carving an Indian figure out of a stump I have looked at for about five years. Many mornings I listened to Native American music while the sun came up or when chiseling away. Regretfully, I’m about finished now, so I will move on and find a new project. My time spent finishing my Indian carving will be full of thoughts of the people who might have passed through here.

I have a family story that I had Indian relatives living in northern Mississippi. They were mostly white, but people knew they had Indian (I think Cherokee) blood, so they were ordered to leave with one of the last groups that left on the Trail of Tears. The story goes that the woman, later known as “Little Grandmother,” kept a little cup tied around her neck. When they got to the Wattensaw River she took a drink of the water and thought it had healthful powers. They made a plan to escape in this area. They traveled by night and hid the children under baskets during the day. I think they made their way to the Des Arc, Arkansas, area. They say when “Little Grandmother” was close to death she told her son if she had one more drink of that good Wattensaw water she believed she could live another year. The only names I know might be connected to this story are from my Guess, Eiland, or Perry family lines.