calsfoundation@cals.org

Howard Jacob Simon (1902–1979)

During the 1920s and 1930s, Howard Jacob Simon was a nationally celebrated painter in oils and watercolors and an illustrator in sketches and woodcut prints. In Arkansas, he was best known for his drawings and woodcuts that illustrated Charlie May Simon’s books and the book Back Yonder, An Ozark Chronicle by Wayman Hogue, Charlie May Simon’s father.

Howard Simon was born on July 22, 1902, in New York City to Samuel Simon, a salesman of general merchandise, and Bertha Simon. He had one brother. Before he was fifteen, Simon knew that he wanted to be an artist. He went daily to the National Academy of Design. He then spent two years at the New York Academy of Arts and drawing for New York newspapers. By the time he was seventeen, he had saved enough money to go to Paris to live and study art for five years.

Simon studied for several years under Jacques Alexander at Académie Julian in Paris. In 1926, he met and married Charlie May Hogue, who was in Paris studying sculpture.

Simon’s career began in earnest in Paris, where he made drawings of the beggars living under the bridges. He learned his woodblock technique from Japanese instructors. Upon returning from Paris, he and his wife settled into a small studio in San Francisco, California, in 1928.

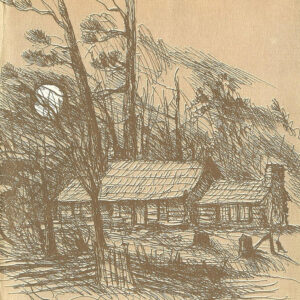

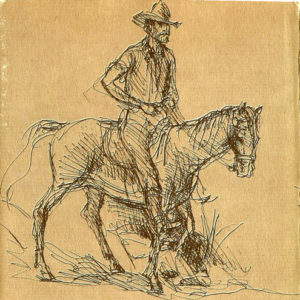

From 1930 to 1935, the Simons lived outside Hollis (Perry County), having moved to Arkansas because of Charlie May’s desire to live as her ancestors had, and built a log cabin. Simon made sketches of the natives, bartering the sketches for services, food, or items they had made. Living in the hills gave Simon the models he needed to illustrate Wayman Hogue’s Back Yonder and many of his wife’s books. In fact, the woodcut titled “Square Dance” was created straight from a dance that he and Charlie May gave for their neighbors. He also illustrated an edition of François Rabelais’s work, François-Marie Arouet de Voltaire’s Candide, and Oscar Wilde’s The Nightingale and the Rose.

Simon divided his time between Arkansas and his native New York, where he served on the art faculty of New York University for twenty years. While in Arkansas, Simon confined himself to woodcuts and etchings rather than oils and watercolors. He often left the hills for art shows in New York, Little Rock (Pulaski County), and Memphis. His work was exhibited at the Smithsonian as well as in New York and San Francisco and was represented abroad at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Simon was a full member of the California Society of Etchers.

Simon kept his ties to Arkansas for much of his life even though he and Charlie May divorced in 1936, partly because Howard did not like living the life of a homesteader. Simon continued illustrating Charlie May’s books for many years. When he was asked to design woodcuts to be published in the Arkansas Gazette for Arkansas’s Centennial celebration in 1936, he designed a woodcut depicting the Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto and his men.

Simon’s second wife was Mina Lewiton, also a writer of children’s literature, whose works he illustrated. They had one daughter. Mina died in 1970. Simon later married Pony Bouche. They had no children.

In 1970, Simon published the autobiographical Cabin on a Ridge, which details the five years of Simon’s life in Arkansas, the building of his log cabin, and the life of the mountain people. Charlie May is not mentioned in this account. Simon’s 500 Years of Art in Illustration was published by the World Publishing Company in 1942. It covers art from the 1400s to the 1940s in many countries.

In 1971, Simon joined the faculty of the Barlow School in Amenia, New York, and became the chairman of the art department in 1972. He had a stroke in August 1979, and in June 1979, the Barlow School dedicated a new building, the Simon Art School, to him. At the time of his death, he was artist-in-residence at the school.

Simon died in White Plains New York on October 15, 1979.

For additional information:

McConnel, Carolyn Cherry. “An Artist Goes Native.” Arkansas Gazette. March 6, 1932, pp. 1, 5.

Obituary of Howard Simon. The New York Times. October 17, 1979, p. 23D.

Simon, Howard. Cabin on a Ridge. Toronto: The Ryerson Press, 1970.

Jody Parsons

Bella Vista, Arkansas

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Cabin on a Ridge

Cabin on a Ridge  Centennial Celebration Woodcut

Centennial Celebration Woodcut  Granny Harris

Granny Harris  Old Man with Pipe

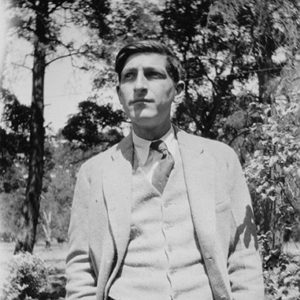

Old Man with Pipe  Howard Simon Self-Portrait

Howard Simon Self-Portrait  Charlie May and Howard Simon

Charlie May and Howard Simon  Howard Simon

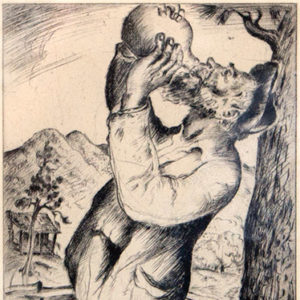

Howard Simon  Uncle John Takes a Drink

Uncle John Takes a Drink

Howard Simon was my first art teacher at NYU in the ’60s. He commented that my sketch of the male model was like that of Glotzius. “Glotzius”? When I went home and looked up Glotzius, I thought, “Sure enough!” My early experience with drawings and artwork attest to the fact that art skill need not necessarily be taught. My first-grade teacher, Julia Rafkin, P.S. 199, Brooklyn, May 1942, sent a letter to my mother, saying, “Carol definitely has talent in art.” Now, during a fifty-year art career, I have art included in the V&A Museum, Hermitage Museum, Zimmerli Museum, Spencer Museum, NYC Library Print Collection, Rockefeller Collection, IBM, MSK, and Carnegie Corp. I do art to surprise myself, and I do!!

In the 1940s, Howard Simon taught at the School of Industrial Art, a vocational high school in New York City, where I was one of his devoted pupils. Mr. Simon was an extraordinarily gifted and inspiring teacher; our group of serious wanna-be artists who were privileged to know him will never forget him. He was also most kind, taking a warm interest in our home lives and our general well-being. Once a week, he had an after-school Illustration Club. There were students there who probably had never read a book in their lives who were reading and illustrating Dostoyevsky. He often had us draw from the model and encouraged us to sketch, sketch, sketch wherever we were. And so we didon the bus, in the subway, the dentists waiting room, during our lunch hour, and of course at home after school. We loved going to schoolweekends and vacations were a punishment. I recall how after our vacations, wed return to school dragging bags and suitcases full of our sketches to show to Mr. Simon. His daughter, Bettinawhom I remember as a little girl being dragged off the field on May Day in Van Courtland Park because she couldnt dance around the Maypole with the big girlsgrew up to be a doctor in Philadelphia.