calsfoundation@cals.org

Fargo Agricultural School

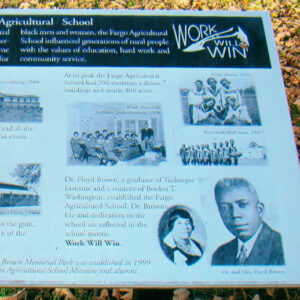

Before the state of Arkansas made public funds available for segregated schools for black children, Floyd Brown, a graduate of Tuskegee Institute, founded and operated the Fargo Agricultural School (FAS) outside Brinkley (Monroe County). From 1920 to 1949, the private residential school offered “training for the head, hands and heart” and high school educations for hundreds of black youth at a time when the United States’ black population averaged five years or less of formal schooling.

In early twentieth-century Arkansas, African-American children were seldom educated beyond the primary grades. In the 1920s and 1930s, most black Southerners were sharecroppers indebted to white landowners to whom they gave a share of their crops for rent. To supplement the family income, women often worked as cooks, housekeepers, laundresses, and nursemaids to the children of white landowners. Doctors, teachers, and clergymen headed only a few rural African-American households, and only two to three percent owned their own houses.

In 1915, Brown, a Mississippi native and recent Tuskegee Institute student, visited Brinkley and found himself drawn to the area. In 1919, Brown returned to Arkansas with $2.85 in his pocket and a plan to transform the educational landscape for black youth in the Delta. Brown financed the purchase of twenty acres of land in Fargo (Monroe County), three miles north of Brinkley, for the establishment of the Fargo Agricultural School, having convinced local supporters to donate the labor and supplies necessary for the construction of classrooms, dormitories, and barns. Classes began on January 1, 1920, and for thirty years, Brown, along with his wife, Lillie Epps Brown—a native of Olyphant (Independence County)—and a small group of dedicated teachers, made the privately owned, nondenominational, coeducational Fargo Agricultural School a unique institution for black children in Arkansas.

(Other secondary and vocational schools for black youth had existed in Arkansas since the 1880s, but these were typically operated by the missionary societies of various Christian denominations. The Freedom Board of the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A., for example, operated the Cotton Plant Academy from the late 1880s until 1932.)

With the apparent blessing of state political leaders and businessmen in the Brinkley area, as attested to by friendly letters addressed to Brown by governors of Arkansas, Brown shaped the curriculum of the FAS to reflect the philosophy of Tuskegee founder Booker T. Washington, as well as the job market for black Southerners. FAS offered a half-day of academic studies—English, music, history, mathematics, and natural sciences. During the other half-day, girls studied childcare, family income management, food preparation, serving and preservation, and sewing. “No matter how poor you are, have something pretty,” Lillie Epps Brown advised her home economics students. Fargo boys learned carpentry, electrical wiring, plumbing, and care of livestock and poultry. They built bookcases, porch swings, and wagon beds; repaired tool handles; and sharpened plows, saws, axes, and hatchets. Floyd Brown made time each week to instruct Fargo students in practical reasoning skills, which he called his “Class in Common Sense.”

Strict standards of conduct were maintained in the FAS dormitories. Girls were housed four to a room in a dormitory with a matron (a faculty member who reported to Lillie Epps Brown). The dean of academic instruction managed the boys’ dormitory. Dormitory supervisors were kept busy enforcing a safe distance between boys and girls at dances and dealing with the usual problems of teenagers.

Brown and the high school choir frequently traveled to elementary schools throughout the Delta to recruit students. Geraldine Purcell Davidson, one of four sisters who attended FAS in the 1930s and 1940s, said her parents “went without proper clothing” to pay Fargo’s $15 monthly room, board, and tuition fees because they “wanted something for their children that they didn’t have.” Brown exhibited a palpable sense of purpose and a strong work ethic, being described by one student as “a black prince.” The school motto, “Work Will Win,” served as the title of a 1994 video documentary about FAS and the lasting impression President Brown made on his young charges.

In 1949, an ailing Brown sold the 800-acre FAS facility to the state of Arkansas. The facility became the Fargo Negro Girls Training School. Brown and his wife moved to Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), where Floyd Brown died in 1961; his widow lived until 1994. Although the Browns were childless, their legacy survives in the memories of hundreds of FAS alumni who attend reunions. A small FAS museum, supported by alumni, was built in 1960 and is located at the Arkansas Land and Farm Development Corporation (ALFDC) facility on the original Fargo Agricultural School grounds.

The Fargo Training School Historic District was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 27, 2010.

For additional information:

Brown, Floyd. He Built a School with Two Dollars and Eighty-Five Cents: His Friends Tell the Story in this Book. Fargo, AR: 1956.

Davidson, Geraldine Purcell. “Interview with Geraldine Purcell Davidson: Fargo Agricultural School.” Audio online at Butler Center AV/AR Audio Video Collection. Geraldine Purcell Davidson Interview (accessed August 19, 2023).

Fargo Agricultural School Museum. Brinkley, Arkansas.

“Fargo Training School Historic District.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Floyd Brown Microfilm Collection. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Freeman, Helaine R. “Fargo School Museum Cultivates Memories of Many Past Glories.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. February 20, 1996, p. 14D.

Hill, Jack, producer. Work Will Win: A History of the Fargo Agricultural School. Video Documentary. Little Rock: Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism, 1994.

Irons, Peter. “Jim Crow’s Schools.” American Educator 28 (Summer 2004): 4–7.

Schnedler, Jack. “Black History Center of Fargo Museum.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 22, 2020, pp. 1E, 6E.

Welch, Dorether M. “Fargo Agricultural School (FAS) (1919–1949): The Hampton-Tuskegee Idea Continued?” PhD diss., University of Missouri–Kansas City, 2003.

Kae Chatman

Little Rock, Arkansas

ALFDC Business Center

ALFDC Business Center  Floyd Brown

Floyd Brown  Fargo Agricultural School

Fargo Agricultural School  Fargo Agricultural School

Fargo Agricultural School  Fargo Agricultural School Ruins

Fargo Agricultural School Ruins  Fargo Basketball Team

Fargo Basketball Team  Fargo Football Team

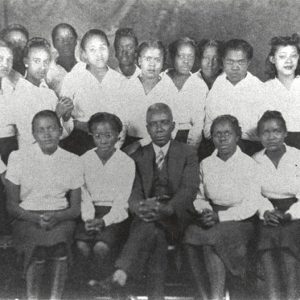

Fargo Football Team  Fargo Girls Chorus

Fargo Girls Chorus  Fargo Girls Dorm

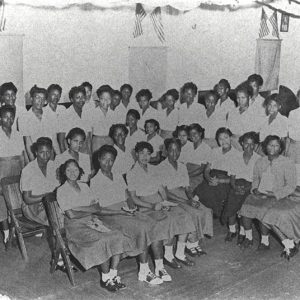

Fargo Girls Dorm  Fargo School Girls

Fargo School Girls  Fargo School Sign

Fargo School Sign  Fargo School Students

Fargo School Students  Fargo Sewing Class

Fargo Sewing Class

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.