calsfoundation@cals.org

Jerome Relocation Center

The Japanese American relocation site at Jerome (in Drew County and partially in Chicot County) was listed on the Arkansas Register of Historic Places on August 4, 2010. This Japanese American incarceration camp, along with a similar one built in Desha County, eventually housed some 16,000 Japanese Americans forcibly removed from the West Coast during World War II. The Japanese American population, of which sixty-four percent were American citizens, had been forcibly removed from the West Coast under the doctrine of “military necessity” and incarcerated in ten relocation camps dispersed throughout the inner mountain states and Arkansas. This was the largest influx and incarceration of any racial or ethnic group in Arkansas’s history. The Jerome Relocation Center was in operation for 634 days—the fewest number of days of any of the relocation camps.

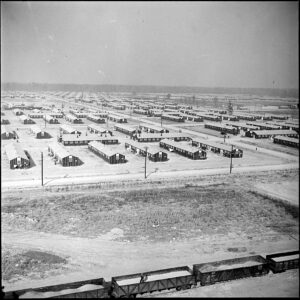

The Jerome site consisted of tax-delinquent lands situated in the marshy Delta of the Mississippi River’s flood plain and was purchased by President Franklin Roosevelt’s Farm Security Administration chief, Eli B. Whitaker. The lands, in dire need of clearing, development, and drainage, were in Drew and Chicot counties. The camp was built eight miles south of the small farming town of Dermott (Chicot County) and was connected by rail to the Rohwer Relocation Center (Desha County) by the Missouri Pacific Railway system. The entire Jerome site encompassed 10,054 acres situated between the Big and Crooked bayous. The A. J. Rife Construction Company of Dallas, Texas, built the Jerome camp at a cost of $4,703,347. In operation from October 6, 1942, to June 30, 1944, Jerome held 8,497 Japanese Americans at its peak. The compound eventually became nearly 500 acres of tarpapered, A-framed buildings arranged into specifically numbered blocks. Each block was designed to accommodate around 300 people in fourteen residential barracks with each barrack (20’x120′) divided into four to six apartments. (This was the traditional military style for barracks, though the internees rebuilt or remodeled the insides.) Each block also included a recreational building, a mess hall, a laundry building, and a building for a communal latrine. All the residential buildings were without plumbing or running water and were heated during the winter months by wood stoves. The camp also had an administrative section that was segregated from the rest of the camp to handle camp operations, a military police section, a hospital section, a warehouse and factory section, a segregated residential section of barracks for white WRA personnel only, barracks for schools, and auxiliary buildings for such things as canteens, motion pictures, gymnasiums, auditoriums, motor pools, and fire stations. The camp itself was partially surrounded by barbed wire or heavily wooded areas with guard towers situated at strategic areas and guarded by a small contingent of military soldiers.

The Jerome Center was officially declared open (although it was not completed) in September 1942, and its population reached 7,932 in January 1943. The project director of Jerome was Paul A. Taylor until the last few months of the camp’s operation. Eli B. Whitaker, former regional director of both camps in Arkansas, assumed duties as project director when Taylor took a higher position in the WRA.

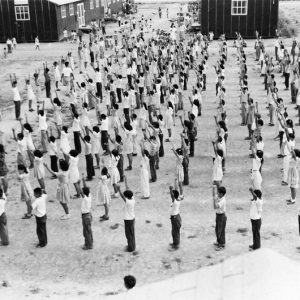

The constant movement of camp populations makes completely accurate statistics difficult; however, as of January 1943, with a population of 7,932 that was engaged predominantly in agricultural work before the war, thirty-three percent of the men and women in the Jerome Camp were aliens—fourteen percent over the age of sixty. Sixty-six percent were American citizens—thirty-nine percent under the age of nineteen. There were 2,483 school age children in the camp—a full thirty-one percent of the total population.

The incarcerated Japanese American youth at the Jerome camp had the most negative reaction to the Army’s forced loyalty and military draft program initiated in February 1943. Several hundred young Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans, born in the U.S.) peacefully marched to the camp director’s building and petitioned against the program.

The first of the ten relocation camps to close, Jerome was used as a German POW camp until the end of the war in Europe. Today the site is mostly used as farmland, although a monument marks the former camp. The remnants of the hospital smokestack can also be seen south of the monument. An internment camp museum opened in McGehee (Desha County) in 2013.

For additional information:

Anderson, William G. “Early Reaction in Arkansas to the Relocation of Japanese in the State.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 23 (Autumn 1964): 196–211

Bearden, Russell E. “The False Rumor of Tuesday: Arkansas’s Internment of Japanese-Americans.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Winter 1982): 327–339.

———. “Life Inside Arkansas’s Japanese American Relocation Centers.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Summer 1989): 169–196.

“Home Movie: 010114: Jerome, Arkansas Relocation Center, ca. 1944.” Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/010114Jerome_201710 (accessed February 26, 2021).

Howard, John. Concentration Camps on the Home Front: Japanese Americans in the House of Jim Crow. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Imahara, Walter M, and David E. Meltzer, ed. Jerome and Rohwer: Memories of Japanese American Internment in World War II Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

Kim, Heidi, ed. Taken from the Paradise Isle: The Hoshida Family Story. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2015.

Life Interrupted: The Japanese American Experience in WWII Arkansas. http://ualr.edu/lifeinterrupted-2race/ (accessed January 8, 2021).

Maude H. Boen Collection. University of Central Arkansas Archives and Special Collections, Conway, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://uca.edu/archives/m87-06-maude-h-boen-collection/ (accessed March 17, 2021).

Sata, Frank T., with Naomi Hirahara. Kagoshima 9066 Westridge: The Life and Art of J. T. Sata, a Japanese Immigrant in Search of Western Art. Altadena, CA: Raymond Press, 2020.

Time of Fear. VHS, DVD. PBS Home Video, 2004.

Wu, Hui. “Writing and Teaching behind Barbed Wire: An Exiled Composition Class in a Japanese-American Internment Camp.” College Composition and Communication 59, no. 2 (December 2007): 237–262.

WWII Japanese American Internment Museum. McGehee, Arkansas. http://rohwer.astate.edu/plan-your-visit/museum/ (accessed January 8, 2021).

Russell E. Bearden

White Hall, Arkansas

Kochiyama, Yuri

Kochiyama, Yuri Camp Shelby Dance

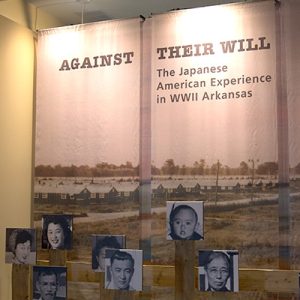

Camp Shelby Dance  Japanese American Internment Museum

Japanese American Internment Museum  Japanese American Internment Museum Display

Japanese American Internment Museum Display  Jerome Buildings

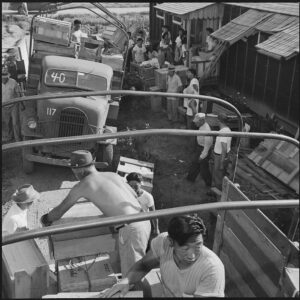

Jerome Buildings  Jerome Closing

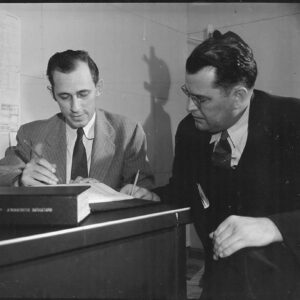

Jerome Closing  Jerome Directors

Jerome Directors  Jerome Relocation Center School Children

Jerome Relocation Center School Children  Jerome Relocation Center Hospital Crew

Jerome Relocation Center Hospital Crew  Jerome Relocation Center Children

Jerome Relocation Center Children  Jerome Relocation Center

Jerome Relocation Center  Jerome Relocation Center

Jerome Relocation Center

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.