calsfoundation@cals.org

World War I

aka: The Great War

World War I had less impact on the state of Arkansas than the Civil War or World War II. Still, World War I did deplete the young male population of the state for a time, brought new institutions into the state that continue to the present time, and gave many Arkansans a new view of the world and of Arkansas’s place in an increasingly connected world community.

World War I was the result of many complex factors, including a network of alliances linking the larger powers in Europe and the growing power of nationalism in some regions of the world. The Balkan region of southeastern Europe—which had been part of the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Austrian Empire—was seeking independence with the encouragement of the Russian government; the assassination of Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914, ignited a summer of conflict in Europe and Africa, combat that would involve the United States and last more than four years. Generally called the “Great War” at the time, it involved fifteen nations sending roughly 65 million soldiers into combat, of which 8.5 million were killed, 21 million were injured, and 7.7 million were captured or missing. The war changed governments in Germany and Austria—as well as Russia, with a revolution that created the Soviet Union. The war also brought about new military technology, including barbed wire, machine guns, poisoned gas, armored vehicles, and the increasingly efficient use of submarines and airplanes for military purposes.

When the war first began, the United States and its government were determined to remain outside the hostilities. Aside from its traditional isolationist attitude, the United States was also more concerned about civil war in neighboring Mexico than it was with fighting on other continents. Arkansas soldiers were sent to New Mexico in 1916 to serve as part of a border guard, although they remained on United States territory and did not engage in any fighting. When he ran for reelection in 1916, Woodrow Wilson reminded voters that he had kept the United States out of war. In spite of this, however, Wilson committed the United States to the alliance that included France and Great Britain when war was declared on Germany on April 6, 1917, less than a month after the inauguration that began his second term. Among the reasons for this change in policy was the fact that American ships had been sunk by German submarines, which were attempting to enforce a blockade of the British Isles. The Arkansas National Guard was incorporated into the U.S. Army, and all men aged twenty-one to thirty were required to register for military service. By June 5, 1917, a total of 149,207 Arkansans had registered (only about 600 eligible men failed to register); after the age limit was increased to forty-five the next year, 199,857 Arkansans had registered.

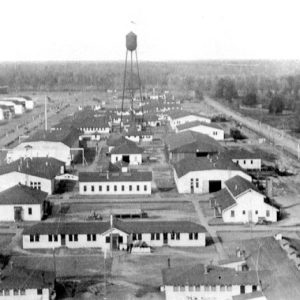

Even before the United States entered the war, the fighting in Europe and elsewhere was affecting Arkansas. Armies needed cotton for uniforms and bandages, increasing the prices paid to cotton growers in Arkansas. Lead and zinc mining increased dramatically in Arkansas during the war years, and a factory in Helena (Phillips County) employed hundreds of workers who crafted rifle stocks from local hardwoods. The sudden enlistment of thousands of Arkansans into the military caused a labor shortage in Arkansas, even as new job opportunities were being provided in the construction of Camp Pike (now Camp Joseph T. Robinson) in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Eberts Field in Lonoke County. Colleges and universities in Arkansas struggled to remain open while most of their students went off to fight; Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) programs often provided the best source of income for institutions of higher education in Arkansas during the war years.

Meanwhile, physical examinations of prospective soldiers revealed chronic health problems in Arkansas, including hookworm, pellagra, and venereal diseases. After the end of the war, several agencies would cooperate to try to reduce or eliminate these sicknesses in Arkansas and other states.

Training of soldiers in Arkansas required larger facilities than the U.S. armed forces possessed at the time. The Little Rock Board of Commerce negotiated an arrangement that raised money to purchase and develop land north of the Arkansas River, now adjacent to North Little Rock. Three thousand acres were purchased outright, and another 10,000 acres were leased. Objections to the new camp included the prevalence of mosquitoes in the area, the lack of a sufficient supply of fresh water, and the lack of adequate transportation to the site. Many of these objections came from the leadership at Fort Logan H. Roots, which had opened on land closer to the Arkansas River in 1897. Money was raised to correct all these problems—at least $325,000, including $187,000 for land acquisition and $60,000 for leases of additional land—and the camp was built and operational before the end of 1917. Camp Pike was named for General Zebulon Montgomery Pike.

Pulaski County hoped also to provide a home for the U.S. Army’s new flying school, but Lonoke County outbid Pulaski County for it. Eberts Field—named for Captain Melchior McEwan Eberts, an early Arkansas aviator—was built during the winter of 1917–18 and began training approximately 1,000 cadets by the spring of 1918. The first graduating class completed its instruction in the middle of November 1918, just days after the fighting ended. The school continued to operate through 1919 before it was decommissioned.

Bond drives were conducted in Arkansas as in other states throughout the course of American involvement in the war. These bonds not only financed the nation’s war effort but also kept awareness of the war high in the minds of most citizens. Purchase of war bonds was described as a patriotic duty, and those who failed to purchase bonds were viewed with suspicion by their neighbors.

The American Red Cross also began its activity in Arkansas during World War I. The first Arkansas chapter of the Red Cross was formed in Garland County in 1917, followed by one in Pulaski County that same year and another in northeastern Arkansas the following year, but Red Cross activities took place in every part of the state. Contributions of money were solicited, and women gathered to prepare bandages and other supplies for the soldiers, including handkerchiefs, pajamas, and socks. African-American groups participated as completely and as enthusiastically as white groups in these activities. So popular was the work of the Red Cross that, in May 1918, a citizen of Saline County was publicly beaten for daring to speak against its efforts.

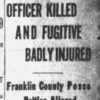

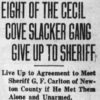

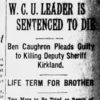

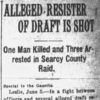

Other Arkansans also suffered because of unpopular attitudes toward the war. Groups of Russellites (who would later adopt the name Jehovah’s Witnesses) refused to participate in the national war effort because of their concerns that loyalty to the United States might conflict with loyalty to God. In Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County), five Russellites were jailed and then taken from the jail, tarred, feathered, and driven out of town because of their refusal to support American war efforts. In July 1918, in an event that became known as the Cleburne County Draft War, shots were fired while local authorities tried to register Bliss Atkinsson for the draft at his father’s home. The Atkinssons and their friends retreated to the wilderness, where they hid while more than 200 officials (including soldiers from Camp Pike, who brought two machine guns) sought them. After a few days, the Atkinssons surrendered to authorities. According to records, 8,732 men in Arkansas either evaded the draft or later deserted.

Suspicion of the state’s German Americans also led to a few isolated instances of violence. On April 13, 1917, local government officials arrived at the Subiaco Abbey in Logan County, seeking to destroy the abbey’s radio to prevent the monks from receiving messages from the government of Germany. The next year, in Lutherville (Johnson County), Pastor Roerig of the Lutheran Church was driven from his house and threatened by gunmen. Some Lutheran and Catholic congregations began worshiping in English rather than in German, and the German National Bank and German Trust Company in Little Rock changed their names to the American National Bank and American Trust Company.

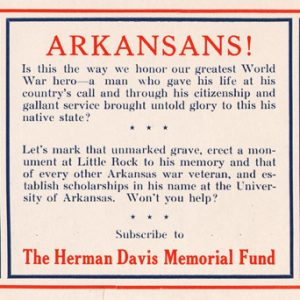

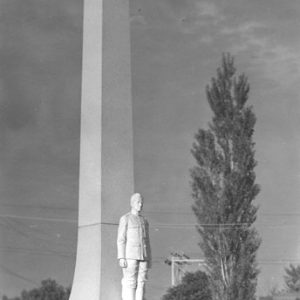

War heroes from Arkansas included Herman Davis of Manila (Mississippi County), who earned several awards for his actions in France and is memorialized by Herman Davis State Park. Oscar Franklin Miller of Franklin County, who was included with Davis on General John J. Pershing’s list of 100 heroes from World War I, won the Medal of Honor, as did Marcellus Chiles and John Pruitt. John McGavock Grider of Osceola (Mississippi County)—for whom the airport in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) is named—and Field Eugene Kindley of Pea Ridge (Benton County) were important fliers in the Army Air Force during the war.

Because the United States entered the war nearly three years after it began, American casualties in the war were far fewer than those of European nations. From Arkansas, 71,862 soldiers served in the war; according to registration cards, 18,322 of these soldiers were African Americans and two were Native Americans. Out of these soldiers, 2,183 died (more than half from illnesses rather than war injuries), and 1,751 were injured.

An indirect result of the war led to far more deaths, however. Relocation of thousands of people caused the spread of an influenza virus known as the Spanish flu. Outbreaks of flu at Camp Pike prompted quarantine of the camp, but the disease still spread throughout the state. Approximately 7,000 Arkansans died of the flu in 1918, more than triple the number of lives lost in the war.

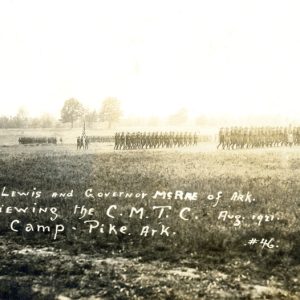

The end of the war brought thousands of returning soldiers to Arkansas, men who had seen violence and mayhem and who had become familiar with other parts of the world. Colleges and universities welcomed new and returning students. Prices fell for cotton, lead, and zinc. Camp Pike was deeded to Arkansas under the condition that 6,000 acres continue to be used for military purposes and could be reclaimed by the U.S. government. Other land was returned to its earlier owners. The camp continued to be used as the headquarters of the Arkansas National Guard and also housed Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers in the 1930s. A civilian training program also continued at the site until the end of the 1930s; known as the Civilian Military Training Camp (CMTC), it was a four-year course (one month each summer). The cadre was provided by the Army Reserves. Colonel Harry S. Truman, future U.S. president, was commander of the Camp Pike CMTC from August 17 to August 30, 1933. The Red Cross remained active in Arkansas and was present to provide aid during the Flood of 1927, the Drought of 1930–31, the Flood of 1937, and later catastrophes.

For additional information:

Allen, Desmond Walls. Index to Arkansas’s World War I Soldiers. 7 vols. Conway, AR: Arkansas Research, Inc., 2002.

Arkansas and the Great War. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. http://bc-digital.org/arkansas-and-the-great-war/index.html (accessed December 6, 2023).

Arkansas World War I Centennial. https://www.arkansasheritage.com/learn/commemorative-programs/wwi-centennial-commemoration (accessed December 6, 2023).

Carruth, Joseph. “World War I Propaganda and Its Effects in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56 (Winter 1997): 385–398.

Christ, Mark K., ed. The War at Home: Perspectives on the Arkansas Experience during World War I. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Craig, Robert D. “Jackson County Supports World War I.” Stream of History 51 (November–December 2018): 13–43.

Finley, Randy. “Black Arkansans and World War One.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49 (Autumn 1990): 249–277.

Hanley, Ray. Camp Robinson and the Military on the North Shore. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

Herndon, Dallas T. Centennial History of Arkansas. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1922.

Hill, Elizabeth Griffin. Faithful to Our Tasks: Arkansas’s Women and the Great War. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2017.

Nieser, Tracy. “The History of Camp Pike, Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 41 (Fall 1993): 64–71.

Polston, Michael David. “Armistice in Arkansas.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 28, 2018, pp. 1H, 6H.

Polston, Michael D., and Guy Lancaster, eds. To Can the Kaiser: Arkansas and the Great War. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2015.

Polston, Mike. “‘Dear Home Folks’: The Camp Pike Letters of an Iowa Sammy in the Great War.” Pulaski County Historical Review 62 (Fall 2014): 70–76.

———. “‘The Time for Rejoicing Has Begun: Little Rock and the End of the Great War.” Pulaski County Historical Review 63 (Fall 2015): 91–93.

Robertson, Brian K. “‘Enough Scalps… to Paper a Room in the Kaiser’s Palace’: The World War I Letters of Maxwell J. Lyons.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 76 (Winter 2017): 308–333.

Robertson, Brian K., ed. “Duane Swift, Conscientious Objector in World War I.” Independence County Chronicle 59 (July 2018): 20–36.

Schmidt, Kyra. “Hello Girls on Strike: Telephone Operators, the Fort Smith General Strike and the Struggle for Democracy in Great War Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2020.

Willis, James F. “The Cleburne County Draft War.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 26 (Spring 1967): 24–39.

Steven Teske

CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Arkansas Colored Auxiliary Council of Defense

Arkansas Colored Auxiliary Council of Defense Arkansas Council of Defense

Arkansas Council of Defense Atkinson, Willie Emmett

Atkinson, Willie Emmett Bolling, Raynal Cawthorne

Bolling, Raynal Cawthorne Bradford, William Claude

Bradford, William Claude Briggs, Clinton (Lynching of)

Briggs, Clinton (Lynching of) Cooke, Charles Maynard "Savvy," Jr.

Cooke, Charles Maynard "Savvy," Jr. Horner, Elijah Whitt

Horner, Elijah Whitt Hospital Unit T

Hospital Unit T Little Rock Aviation Supply Depot

Little Rock Aviation Supply Depot Little Rock Picric Acid Plant

Little Rock Picric Acid Plant Logan County Draft War

Logan County Draft War McLaughlin, William Heber

McLaughlin, William Heber Military

Military Newton County Draft War

Newton County Draft War Polk County Draft War

Polk County Draft War Searcy County Draft War

Searcy County Draft War Spirit of the American Doughboy Monuments

Spirit of the American Doughboy Monuments World War I Markers and Memorials

World War I Markers and Memorials African American WWI Draftees

African American WWI Draftees  William Claude Bradford

William Claude Bradford  Ida Joe Brooks

Ida Joe Brooks  Charles Brough

Charles Brough  Camp Pike

Camp Pike  Camp Pike Dance

Camp Pike Dance  Camp Pike Nurses

Camp Pike Nurses  Camp Pike

Camp Pike  Herman Davis Funeral

Herman Davis Funeral  Herman Davis Memorial Flyer

Herman Davis Memorial Flyer  Herman Davis Monument

Herman Davis Monument  Eberts Field Airplane

Eberts Field Airplane  Eberts Training Field Gunnery Plane

Eberts Training Field Gunnery Plane  Eberts Training Field

Eberts Training Field  Field Kindley

Field Kindley  Little Rock Aviation Supply Depot

Little Rock Aviation Supply Depot  Paragould Recruits

Paragould Recruits  SATC Inductees

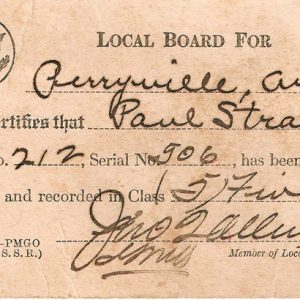

SATC Inductees  WWI Draft Card

WWI Draft Card  World War I Soldiers

World War I Soldiers  World War I Soldiers

World War I Soldiers

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.