calsfoundation@cals.org

Dwight Mission

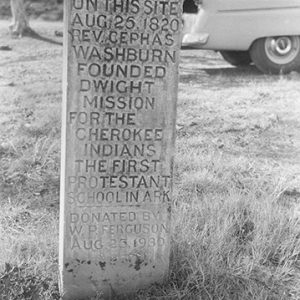

Dwight Mission near Russellville (Pope County) was the first formal Protestant effort directed at the education and conversion of Native Americans in Arkansas and was one of the first Protestant missions established west of the Mississippi. The mission was established in 1820 and operated in Arkansas until 1829.

The mission had been requested by Western Cherokee Principal Chief Tahlonteskee in 1818, when he visited Brainerd Mission in Georgia, sponsored by the American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions (ABCFM), a Presbyterian organization. The Western Cherokee was a diverse group whose previous generation had migrated into Arkansas while fleeing troubles in the Cherokee homeland at the southern end of the Appalachians, and some of the members thought it useful for their children to be formally trained in Anglo-American ways. Not all felt this way, however. By the time Dwight Mission was established in 1820, Tahlonteskee was dead of natural causes. War Chief Takatoka opposed the effort, and it is probably no accident that he suggested the eventual site of the mission be located not far from his own headquarters at Spadra Creek (modern-day Clarksville in Johnson County) so that he could keep it under observation. Even Cherokee leaders who supported the mission—such as Tahlonteskee’s brother Ooluntuskee (also known as John Jolly), who had succeeded him as principal civil chief—had some misgivings. They knew that the effort to convert their children to Christianity might strip them of much of their Cherokee heritage.

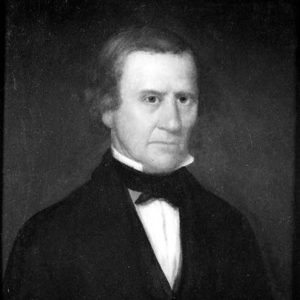

Dwight Mission was located on the west bank of Illinois Bayou about four miles upstream from the Arkansas River. It is marked now by a sign on Highway 64 at a boat ramp that provides access to Lake Dardanelle. No buildings remain, but the cemetery location survives on the hill overlooking the site. The mission was named after Timothy Dwight, who had been president of Yale University and was the first corporate member of the ABCFM. The site was chosen in August 1820 by Cephas Washburn and Alfred Finney, both new young missionaries and New Englanders like most of the rest of the staff. Construction of log residence buildings began soon thereafter. All of the missionary families and additional staff had arrived by December 1821, including one group who had come in a keelboat bought by Washburn and manned by Frenchmen. The school opened on January 1, 1822. Three months later, the mission was resupplied by the Eagle, the first steamboat to reach north of Little Rock (Pulaski County).

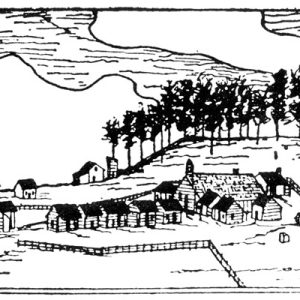

At its fullest expression, the mission station was a completely equipped small town on the Arkansas frontier. These facilities are well documented by a sketch map and plan prepared in 1824 and Washburn’s own 1829 inventory detailing costs and specifications. By 1824, there were at least twenty-four structures, including twelve residences for the missionaries, pupils, hired help, and visitors. Support buildings included a storehouse “containing the charities of a Christian public” (according to a map by Sophronia Hitchcock), one building that was a combination post office and library and drug shop, a dining hall and kitchen facility, and a bell. Craft centers included a blacksmith shop, a lathe shop, and a carpenter shop. Subsistence support buildings housed a farm equipment shed, a corn crib, a smokehouse, a horse stable with yards, a barn, and a harness shed. Several burials had already taken place by 1824 in the cemetery on the hill just west of the mission. The mission also had two gardens; a pasture; fields for row crops, including corn, rye, and oats; two improved springs; and a well.

Student life at the mission included classes in reading, arithmetic, and deportment. For the girls, instruction was given in household skills such as sewing and cooking. The boys were taught farming skills, carpentry, and blacksmithing. On Sundays, adults and children were instructed in Christianity in “Sabbath School,” thus ensuring the melding of the secular and the sacred. The student population varied from twenty to as many as 100. Washburn provided a few anecdotes suggesting that, while the children could be converted, there were difficulties in converting adults, particularly males, and he implied there were not many successes with adults.

When the mission was closed in 1829, it had fifteen residences and twenty-one other buildings. A sawmill and gristmill stood one mile away on Mill Creek with an accompanying house and outbuildings. The residences for the missionaries and the students were full-fledged structures with log walls, stone chimneys, and porches. While it was in operation, the mission served as a school, as a base for preaching efforts by Washburn and others at outlying Cherokee settlements, and as an informal center for medical care.

The mission continued operation in Arkansas until the end of summer 1829, when it was shut down for the move to Indian Territory after the Cherokee ceded their Arkansas lands with the Treaty of 1828. A mission substation had been established on the Mulberry River by May 1828, but the cession treaty ended this effort. Dwight Mission was relocated in late 1829 to near Sallisaw, Oklahoma. It continued with some interruptions as an Indian school supported by Presbyterians until 1948, when it was closed because of other opportunities that then existed for Indian children. The “new Dwight” continued to operate as a Presbyterian meeting facility and summer church camp until 2021, when it was acquired by the Cherokee Nation.

For additional information:

Coleman, Michael C. “Not Race but Grace: Presbyterian Missionaries and American Indians, 1837–1893.” Journal of American History 7 (June 1980): 41–60.

“Dwight Mission.” Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=DW001 (accessed April 17, 2023).

Jones, Dorsey D. Cephas Washburn and his Work in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Journal Series, 1944.

Markman, Robert Paul. “The Arkansas Cherokees: 1817-1828.” Ph.D. diss., University of Oklahoma, 1972.

Payne, Betty, and Oscar Payne. Dwight, A Brief History of Old Dwight Cherokee Mission 1820–1953. Tulsa: Dwight Presbyterian Mission, 1954.

Turrentine, G. R. “Dwight Mission.” Arkansas Valley Historical Papers 25 (1962): 1–11.

Vance, David L. Early History of Pope County. Mabelvale, AR: Foreman Payne Publishers, 1970.

Washburn, Cephas. Reminiscences of the Indians. Conway, AR: Oldbuck Press, Inc., 1993.

Leslie C. Stewart-Abernathy

Arkansas Archeological Survey

Dwight Mission

Dwight Mission  Dwight Mission Monument

Dwight Mission Monument  Cephas Washburn

Cephas Washburn

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.