calsfoundation@cals.org

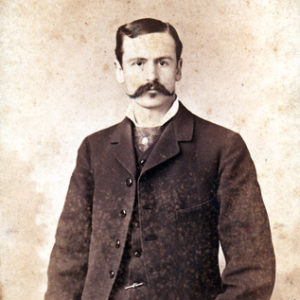

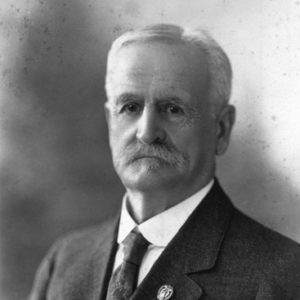

Fay Hempstead (1847–1934)

Fay Hempstead was an attorney, a poet, and a Mason who spent much of his life in the service of the Grand Lodge of Arkansas Freemasons. In addition to his poetical works, he wrote the first school textbook for Arkansas history as well as other historical studies.

Hempstead was born on November 24, 1847, in Little Rock (Pulaski County). His parents were Samuel Hutchinson Hempstead, an attorney and postmaster of Little Rock, and Elizabeth Rebecca Beall Hempstead. Hempstead was educated privately and attended St. Johns’ College, a Masonic institution in Little Rock, from 1859 to 1861. From 1866 to 1868, he studied law at the University of Virginia, returning to Arkansas to practice law. From 1869 to 1872, he was a partner in the firm of George A. Gallagher and Robert C. Newton. He married Gertrude Blair O’Neale of Charlottesville, Virginia, on September 13, 1871. They had seven children.

In 1874, Hempstead became Registrar in Bankruptcy for Arkansas and held this position until 1881, when he was elected Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of Arkansas Freemasons. He spent the rest of his life in service to Freemasonry and was much honored for his work. He was named poet laureate of Freemasonry in 1908, an honor that had previously been accorded only two others, Robert Burns of Scotland (1787) and Robert Morris of Kentucky (1884).

The first volume of his selected poems was Random Arrows (1878). In 1898, 1908, and 1922, further collections were published in Little Rock.

Hempstead’s poetry, like that of many other late Victorians, has not aged well. By the standards of his time, he was an adequate technician. His poems employ a great variety of meters and rhyme schemes. Hempstead used the imagery and rhetoric of an earlier age in poems about contemporary subjects, such as the battles in Manila and Havana, the completion after long delays of the Washington Monument in Washington DC, the threatened extinction of the American bison, and the Memphis Mardi Gras of 1881. But the poems are prone to the archaic language that was despised by the Modernists such as John Gould Fletcher, Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and others of the next generation. The poem “One Hundred Years,” for example, depicts the march of progress through the century of the American republic, describing the railroad Car of Triumph that goes on “bands of compressed steel,” but it is marred by expressions like “God wot!”

For Arkansas readers, however, the subject matter of his poetry holds considerable interest. For example, one long poem, “O-ni-hah-ket,” relates in rhymed couplets a legend of an Indian woman captured by some of Hernando de Soto’s men. Another poem commemorates the Mountain Meadows massacre, and “A New Bethesda” celebrates the mysterious powers of the waters of Hot Springs (Garland County). His collected works contain many “occasional” poems, which, according to the notes that accompany them, commemorate a person or event in Little Rock. One such example is “Woman,” read “at the banquet to General U. S. Grant” in 1880. “A Forsaken Building,” read at a reunion of the alumni of St. Johns’ College in Little Rock, enumerates those fellow students who died in the Civil War. A poem of more than 100 rhymed couplets, titled “De Minimis” (“For the Smallest Thing”), shows how every great thing in nature and in human endeavor has sprung from some lesser origin. This poem was read, presumably by the poet, at the dedication of the Little Rock Commercial College on December 20, 1883.

“The Wrangler” is a response to a series of lectures by J. W. Clarke given in Little Rock. This ambitious long poem is composed in quatrains of rhymed tetrameter. In it, Hempstead attempts to come to terms with the discoveries in geology and biology regarding the origin of the human species and what he calls the “unity of the human race,” questioning whether the Biblical understanding of the “races” of humanity could be justified or whether humanity was one single species. A long note to this poem includes his own conclusion toward a “development theory” that acknowledges God as the starting point of creation, no matter what process followed.

In addition to his poetry, Hempstead published several works on the history of Arkansas and of Freemasonry. In 1889, he published A School History of Arkansas, the first textbook of its kind for use in schools. It contains, in addition to the historical narrative, such textbook apparatus as pronunciation guides, study questions, maps, timetables, and review questions. In 1890, he published A Pictorial History of Arkansas: From Earliest Times to the Year 1890. It begins with the Native American occupants of the region that became Arkansas and takes the history to post–Civil War times. It includes extended histories of each county in the state. He published Historical Review of Arkansas: Its Commerce, Industry, and Modern Affairs (1911), including articles by other specialists. After his appointment to the Masonic secretaryship, he wrote A History of Cryptic Masonry in Arkansas (1922).

Hempstead died in Little Rock on April 24, 1934, and is buried in Mount Holly Cemetery.

For additional information:

Fay Hempstead Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Obituary of Fay Hempstead. Arkansas Gazette, April 25, 1934, p. 1.

Ethel C. Simpson

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Fay Hempstead

Fay Hempstead  Fay Hempstead

Fay Hempstead  Fay Hempstead

Fay Hempstead

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.