calsfoundation@cals.org

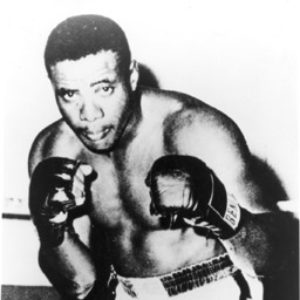

Sonny Liston (1932?–1970)

aka: Charles Liston

Charles “Sonny” Liston was a noted boxer who briefly reigned as Heavyweight Champion after a first-round knockout against Floyd Patterson. However, his career was marred by criminal activity and, later, accusations of mob connections and throwing fights.

Sonny Liston was born on May 8, probably 1932, to Tobe and Helen (Baskin) Liston, African American sharecroppers in rural St. Francis County. He was one of many children—one account lists twenty-two siblings and half-siblings. Liston was raised on heavy farm work, many beatings, and with virtually no schooling. At the age of thirteen, he ran away to St. Louis, Missouri, following his mother, who had left earlier. There, he committed various muggings and robbery. Soon caught (his crimes were inept, spur-of-the-moment, strong arm jobs) and charged with first-degree robbery and larceny, he was sentenced in 1950 to five years in the Missouri State Penitentiary.

In prison, encouraged by Catholic chaplains, Liston took up boxing, where he was an immediate and spectacular success. Paroled in 1952, he had a brief amateur career, winning several Golden Gloves championships and defeating 1952 Olympic heavyweight champion Ed Sanders. Liston turned professional in September 1953, earning his first paycheck in St. Louis with a first-round knockout of Don Smith.

Nine years of steady fighting later, and following additional scrapes with the law (fourteen arrests between 1953 and 1958 and a conviction in 1956 for assaulting a police officer), Liston finally fought Floyd Patterson for the Heavyweight Championship. In the same interval, he had gotten married (in 1957 to Geraldine Clark), moved from St. Louis to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1958, and been questioned by a congressional committee about the takeover of his management by mob elements in 1960. He had earned the title shot with an impressive string of 1959–60 victories over top contenders Cleveland Williams, Nino Valdes, Roy Harris, Zora Folley, and Eddie Machen (all knockouts except for Machen). His ring style was the essence of simplicity; he displayed little finesse but much raw power, especially in his left hand.

The title fight was in Chicago, Illinois, on September 25, 1962, with a wide public pulling for the champ (including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and authors James Baldwin and Norman Mailer). But the champ went down in a hurry: two minutes and six seconds in the first round. Sonny Liston, hard-luck son of Arkansas sharecroppers, was champion of the world. The rematch in Las Vegas, Nevada, on July 22 1963, was another first-round knockout, with Patterson counted out in two minutes, twenty-three seconds.

His time at the summit was brief. Less than a year later, on February 25, 1964, in Miami Beach, Florida, a heavily favored Liston lost his title to upstart Cassius Clay (soon to be Muhammad Ali) when he refused to answer the bell for the seventh round, claiming a shoulder injury. The rematch, in Lewiston, Maine, on May 25, 1965, was even more controversial. Liston went down in the first round, felled by a punch few saw. It was scandal on top of scandal; Liston’s reputation, already tainted by prison time, allegations of mob connections, and charges of sexual assault, never recovered. He continued fighting until June 29, 1970, when he knocked out Chuck Wepner, but he never got another title shot. His final record as a professional was fifty wins, thirty-nine by knockout, and four losses.

Even as champion, Liston was never able to escape his prison beginnings or the allegations of mob connections. He got little good press, even from sports columnists, and was routinely subjected to overtly racist slurs in print: in 1964, Look ran a story titled “Sonny Liston: ‘King of the Beasts.’”

Liston moved to Las Vegas in 1966 and was found dead there on January 5, 1971, when his wife returned to their Las Vegas home from a Christmas visit with her mother. He had been dead for some time. There were rumors of drug peddling, heroin use, and murder, but no answers. The coroner picked December 30, 1970, as the date of death, and Liston was buried in the Paradise Memorial Gardens in Las Vegas under the simplest of epitaphs: “A MAN.”

For additional information:

Assael, Shaun. The Murder of Sonny Liston: Las Vegas, Heroin, and Heavyweights. New York: Blue Rider Press, 2016.

Gallender, Paul. Sonny Liston: The Real Story behind the Ali-Liston Fights. Pacific Grove, CA: Park Place Publications, 2012.

Mee, Bob. Ali and Liston: The Boy Who Would Be King and the Ugly Bear. New York: Skyhorse, 2011.

Steen, Rob. Sonny Liston: His Life, Strife, and the Phantom Punch. London: Aurum Press, 2008.

Tosches, Nick. The Devil and Sonny Liston. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2000.

Robert B. Cochran

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Recreation and Sports

Recreation and Sports World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Sonny Liston

Sonny Liston

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.