calsfoundation@cals.org

Henry Jackson Lewis (1837?–1891)

Henry Jackson Lewis, who was born into slavery, has been called the first black political cartoonist. His drawings appeared in publications across the nation.

H. J. Lewis was born in Water Valley, Mississippi, in 1837 or 1838. As a child, he fell into a fire, maiming his left hand and blinding his left eye. Nothing further is known about his youth, but by 1872, he was living in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), where he worked as a laborer in the mid- to late 1870s.

By 1879, he was selling drawings of city and Arkansas River scenes to the national publication Harper’s Weekly, and he later sold similar drawings to Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. On October 25, 1882, a Pine Bluff Commercial article referred to him as a “caricaturist and pencil artist” whose sketches “of both imaginary and real scenes are wonderfully correct,” and concluded, “We bespeak for him a brilliant and successful future.”

In November 1882, Edward Palmer, a leading archaeological field investigator for the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, hired Lewis as an assistant. Lewis drew Indian mounds and related scenes, as well as maps for Palmer in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee the rest of that year and in early 1883.

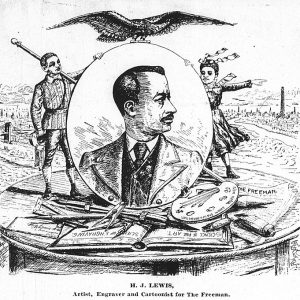

In the mid-1880s, because of a lack of suitable work around Pine Bluff, Lewis went to Little Rock (Pulaski County) and worked at least briefly as a “porter” for the Arkansas Gazette. He later said he learned some artistic techniques from Gazette staff engravers. He also occasionally sold cartoons to the national weekly comic publications Puck and Judge. In January 1889, Lewis moved from Pine Bluff to Indianapolis, Indiana, where he worked for the Freeman, a new “national illustrated colored newspaper.” His wife and seven children soon joined him.

Lewis has been called the first black political cartoonist for his Freeman work. His earlier drawings (February through December 1889) touched on a variety of topics but most notably included several sharp attacks on the policies and personalities of the new Republican administration of President Benjamin Harrison. After October 1889, his cartoons attacking the Harrison administration ceased to appear, perhaps because of economic pressure on the financially troubled Freeman by allies of Harrison, an Indianapolis native. Indeed, no new works by Lewis were published in the Freeman between December 1889 and August 1890.

When Lewis’s drawings reappeared in the paper, they tended to be on humorous subjects or race relations in general, rather than political subjects, except for two cartoons indirectly criticizing Harrison in December 1890 and January 1891. His last published work, a drawing of a new church in St. Louis, appeared in the Freeman on March 28, 1891. By then, his health had declined, reportedly aggravated by the harsh Midwest winters, and he died of a respiratory disease in Indianapolis on April 9, 1891. Obituary notices in the mainstream Indianapolis Journal and in the Freeman referred to him as “a genius,” and the Freeman’s tribute concluded with a wish that he had lived “a completer life, where conditions may not interfere, or man’s narrowness or unfair hatred prevent the full expression of his unique and striking gifts.”

For additional information:

Fellone, Frank. “Drawing on History.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 18, 2015, pp. 1E, 6E.

Jeter, Marvin D. “H. J. Lewis and His Family in Indiana and Beyond, 1889–1990s.” In Indiana’s African-American Heritage, edited by Wilma L. Gibbs. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1993.

———. “H. J. Lewis, Free Man and Freeman Artist.” Commonplace 7 (April 2007). http://commonplace.online/article/h-j-lewis-free-man/ (accessed April 25, 2021).

Jeter, Marvin D., ed. Edward Palmer’s Arkansaw Mounds. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Marvin D. Jeter

Arkansas Archeological Survey

Henry J. Lewis

Henry J. Lewis  Henry Jackson Lewis

Henry Jackson Lewis

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.