calsfoundation@cals.org

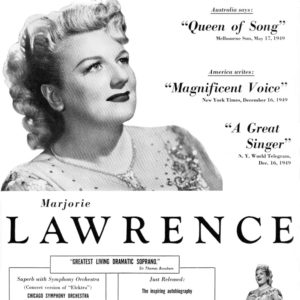

Marjorie Florence Lawrence (1907–1979)

Marjorie Florence Lawrence, an Australian native and star soprano with the Metropolitan Opera Company of New York City, became an exemplar for endurance when she rebuilt her career after being stricken by poliomyelitis (commonly known as polio). Despite the professional opinion that she would never sing again, she started over, first by singing from a wheelchair or platform, and then by managing to stand and sing. The subject of an Oscar-winning motion picture, Interrupted Melody, she later taught at Sophie Newcomb College at Tulane University and for an extended time at Southern Illinois University (SIU) at Carbondale. Beginning in 1941, Lawrence lived outside of Hot Springs (Garland County) and held summer opera coaching sessions at her ranch, Harmony Hills, which advanced the cause of classical music in Arkansas.

Marjorie Lawrence was born on February 17, 1907, at Dean’s Marsh, Victoria, Australia, the fifth of six children of William and Elizabeth Lawrence. After graduating from the local school, she traveled to Melbourne without her father’s permission to study voice with Ivor Boustead. After winning a vocal contest, she studied for three years under Cécile (Madame Dinh) Gilly in Paris, France. In 1932, she made her debut in Monte Carlo as a dramatic soprano, singing Elisabeth in Richard Wagner’s Tannhauser. After more performances at Lille and Nantes, she arrived at the Paris Opera, making her debut there on February 25, 1933, as Ortrud, a mezzo role, in Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin. She then moved back into dramatic soprano roles, singing Brunnhilde in Die Walkure and Gotterdammerung, as well other French and Italian soprano roles. She also recorded for Voix de son maitre (His Master’s Voice). Particularly notable was her rendition of the final scene from Richard Strauss’s Salome, which she sang in Oscar Wilde’s original French text.

On December 18, 1935, she made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, where she soon became a fixture, singing every season until 1940–41. On January 12, 1936, the astonished audience watched when, at the end of Gotterdammerung, she leaped upon her horse and rode into the fires of Siegfried’s funeral pyre. Critics praised her performance of Rachel in Halevy’s La Juive. Lawrence was also busy on the concert circuit; she returned to Australia for a concert tour and also performed at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

On March 29, 1941, she married Dr. Thomas King, a young physician in New York City. Three months later, while rehearsing in Mexico City, she collapsed. Her husband rushed her to Hot Springs in hopes of alleviating her constant pain. First treated at St. Joseph’s Hospital by Dr. George B. Fletcher, she improved to the point that she could go by ambulance daily to the Maurice Bathhouse. It was Fletcher who determined that she had been stricken by polio. Faced with the possibility of nearly total disability, the couple bought a home, which they later named Harmony Hills, from Mary Hedrick that was located on some 500 acres outside of Hot Springs. It remained Lawrence’s home for most of her life, and there she wrote, “We have discovered the real joys of living.”

In hopes of improving her condition, the couple consulted Sister Elizabeth Kenny, an international figure in polio-recovery practices. While Lawrence was being treated by her in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Dr. King learned how to care for Lawrence. One byproduct of these sessions was that Lawrence began to recover the use of her vocal cords. Her first public appearance came on December 21, 1941, at the First Christian Church in Miami, Florida, where the couple had gone for the winter.

Lawrence then worked at rebuilding her career, first on radio in 1942, where, of course, her wheelchair-bound condition was unimportant, and then at a Metropolitan Opera Guild luncheon and at a Town Hall recital. On December 27, 1942, she returned to the Metropolitan, singing from a couch the role of Venus in Wagner’s Tannhauser. She performed in concerts extensively and, in 1943, sang the very demanding role of Isolde in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde in Montreal, with Sir Thomas Beecham conducting. A single Metropolitan performance followed in 1944, but General Manager Edward Johnson (who had partnered Arkansas’s Mary Lewis in her operatic debut at the house in 1926), considered a wheelchair-bound Isolde to be “unsightly.” Support, however, came from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1943: “From an old veteran to a young recruit—my message to you is—‘Carry on!’” She sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” at his 1945 inauguration and later met privately with him.

In 1944, she headed off to the Pacific Theater of World War II, performing for more than 50,000 GIs and “Diggers” (Australians), with special concerts for the critically wounded. The format consisted of her being seated behind a screen that would then be removed at the start of the concert. “Waltzing Matilda,” which she recorded three times, was virtually her signature song. Even in a wheelchair, she still resembled “a big, blond bar maid.”

In 1945, she toured Europe, singing the same mixture of songs and arias that she had featured in the Pacific. She thought she had done poorly during a command performance at Buckingham Palace until she realized the audience members were wearing gloves. Subsequently, she sang with a number of English orchestras and added a new role, Amneris in Verdi’s Aida, first at the Cincinnati Opera Company and then at the Opera in Paris. In occupied Germany, with Russians present, she sang with the Berlin Philharmonic in a program that included Tatania’s “Letter Scene” from Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, as well as her perennial concert favorite, the finale to Gotterdammerung. By 1947, her recovery had reached the point that she could stand and sing. This accomplishment was first displayed in a concert performance of Richard Strauss’s Elektra with the Chicago Symphony conducted by Artur Rodzinski.

Meanwhile, she had been working on her autobiography. Interrupted Melody: The Story of My Life (1949) became a bestseller and, in 1955, was the basis for an Oscar-winning motion picture (for best writing, story, and screenplay). Eleanor Parker (who was nominated for an Oscar) played Lawrence, and soprano Eileen Farrell supplied the vocal numbers. Because Lawrence was best defined as a mezzo who had been induced to take on dramatic soprano roles and Farrell was a soprano, viewers got a slightly distorted notion of Lawrence’s singing. The southern premiere of the film took place at the Malco Theatre in Hot Springs in 1955.

Lawrence moved into television, hosting a television show from 1953 to 1954. She sang publicly during a 1966 visit to Australia, and her last recording, appropriately of “Waltzing Matilda,” was made there in 1976.

In 1957, Lawrence became artist-in-residence at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, where she taught voice at Sophie Newcomb College. In 1960, she moved to SIU in Carbondale, where she became professor of voice and director of opera workshops, remaining there until 1973. Summer workshops were held at Harmony Hills and included students from SIU and other schools. At the conclusion of the workshops, Lawrence presented her students in a public concert in the ballroom of the Arlington Hotel. She also sang with the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra.

In 1974, she began teaching at Garland County Community College (now National Park College) in Hot Springs and joined the faculty at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) in 1975. Ohio University at Athens made her a doctor of humane letters in 1969, and in 1977, she became a dame Commander of the British Empire (CBE).

Lawrence died on January 13, 1979, in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Hot Springs.

Lawrence was one of the major operatic figures during her pre-polio days. Her career is documented by studio recordings ranging in date from 1928 to 1976 and by recorded radio broadcasts from the 1930s to 1950. Her courageous struggle with her disability highlighted the importance of a disease for which at that time there was no cure and no means of prevention. In her memoirs, and then as touched up by Hollywood, Lawrence gave this tragedy a voice and a face. When she attended the gala that marked the opening of the new home for the Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center, her students and admirers provided the funds that gave the hall wheelchair accessibility.

For additional information:

Davis, Richard. Wotan’s Daughter: The Life of Marjorie Lawrence. Adelaide, Australia: Wakefield Press, 2012.

Hogarth, Will, and R. T. See. “Marjorie Lawrence: A Tribute in the Form of a Discography.” The Record Collector 32 (January 1987): 3–18. Extensions, additions, and corrections to the discography appear in The Record Collector 33 (November 1988): 300–303; and The Record Collector 34 (May 1989): 98–100.

Jackson, Paul. Saturday Afternoons at the Old Met: The Metropolitan Opera Broadcasts, 1931–1950. Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1994.

Kolodin, Irving. The Story of the Metropolitan Opera, 1883–1950. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1953.

Lawrence, Marjorie. Interrupted Melody: The Story of My Life. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1949.

“Marjorie Florence Lawrence.” Australian Dictionary of Biography. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lawrence-marjorie-florence-7115 (accessed August 19, 2023).

Mamie Ruth Abernathy

Hot Springs, Arkansas

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Marjorie Lawrence Ad

Marjorie Lawrence Ad  Marjorie Lawrence

Marjorie Lawrence  Marjorie Lawrence

Marjorie Lawrence  Maurice Bathhouse

Maurice Bathhouse

I have very fond memories of living in Harmony Hills during the early 1940s. My father managed the estate, and our family enjoyed a splendid lifestyle during those years. Dr. King and Dr. Fletcher were very influential in my future career selections. Dr. King cured my brother of his stuttering problems. Ms. Lawrence was kind and warm.

Just saw the movie Interrupted Melody on TV–very well done and inspirational. Thank you! I am seventy-nine and from St. Louis; as a kid, I fished in Arkansas.