calsfoundation@cals.org

Ku Klux Klan (after 1900)

The original Ku Klux Klan (KKK) formed sometime between 1865 and 1866 in Pulaski, Tennessee. Nathan Bedford Forrest, the first acknowledged Klan leader, took actions to disband the organization in 1869. A resurgence in Klan activity occurred starting in 1915, and states such as Arkansas were home to newly forming Klan groups during the 1920s. By 1955, the threat of school integration ushered in a new Klan era even though independent Klan groups were a fixture on the American landscape in some way or another from the 1920s on.

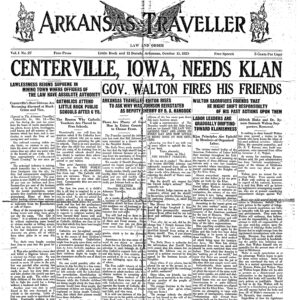

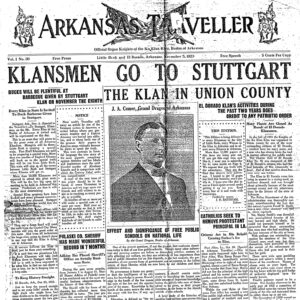

One of the first official Klan acts in Arkansas was a donation to the Prescott (Nevada County) Christmas fund in December 1921. Shortly thereafter, other Klan groups formed with the goal of “cleaning up” local communities—an example set by groups in Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana. Leaders used the Klan as a device to regulate morals and to uphold Victorian standards, especially for women. Bigotry, the Red Scare, and anti-unionism were also important issues for the 1920s Klan in Arkansas and other Southern states. Eventually, enforcement of the prohibition of alcohol became one of the Klan’s leading goals. In 1922, Klansmen in Union County torched saloons that had sprung up after the oil boom, and local bootleggers became a target for Klan reprisals. The state’s Klan newspaper, Arkansas Traveller, was first published in that same county starting in 1923.

Strikes on the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad brought the Ozark region of Arkansas to the attention of early Klan organizers. They effectively targeted the communities of Paragould (Greene County), Jonesboro (Craighead County), Harrison (Boone County), Heber Springs (Cleburne County), and Marshall (Searcy County) as sites for Klan activity. Local resentment toward strikers, as manifest especially in a Harrison riot, enabled the Klan to become entrenched in this part of the state. With support from concerned citizen groups, the Klan was able to gain a following in non-urban Arkansas based on restoring the local economy, severely sanctioning union strikers and their sympathizers, and running bootleggers out of town. However, opposition did emerge, most notably in the publication of The Eagle, an anti-Klan newspaper based in Marshall in the 1920s.

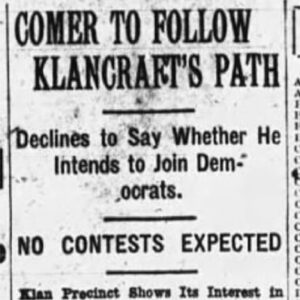

According to historian Charles C. Alexander, the first chartered Arkansas Klan organization was formed during the early 1920s in Little Rock (Pulaski County). The group reportedly retained 7,800 male members during its zenith. More typical of the urban Klan movement of the time, the Little Rock Klan organization was powerful enough to influence local and county politics through “elimination primaries.” In 1922, a slate of Klan-endorsed candidates gained control of Pulaski County politics under the leadership of Exalted Cyclops James A. Comer. Little Rock was also home to a national women’s Klan order that formed in 1923 as an adjunct to the men’s group. Two junior Klan groups were established in 1924 in Little Rock and Arkadelphia (Clark County) as well.

Internal battles and money troubles eventually weakened the Little Rock Klan, and it was in shambles by 1926. Economic woes brought on by the Great Depression further weakened Klan groups throughout the South, and the national Klan organization in Georgia ceased operations in 1944 due to tax problems. During the years following school integration and the end of Jim Crow, Klan groups across the South fragmented due to infiltration by law enforcement, internal conflicts, and lawsuits by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC).

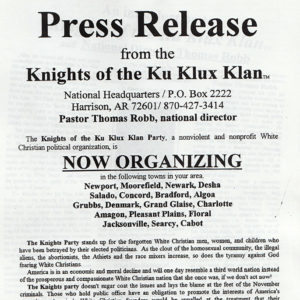

According to the SPLC, a number of KKK groups are active in Arkansas. The group in Boone County, the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, operates under the auspices of Pastor Thom Robb’s Christian Identity ministry. Also known as the Knights Party, the group is considered to be one of the better-organized Klan organizations in the South. Robb’s group is relatively active and continues to sponsor annual events for its members and invited guests, such as a retreat held in April 2009 in the area of Zinc (Boone County) and South Lead Hill (Boone County), which reportedly attracted about fifty people.

In 2016, the Arkansas-based Klan organization made national news when Thom Robb, writing in the Klan newspaper Crusader, endorsed Republican Party candidate Donald Trump for president of the United States.

For additional information:

Alexander, Charles C. “The Ku Klux Klan in Arkansas 1922–1924.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 22 (Autumn 1963): 195–214.

———. The Ku Klux Klan in the Southwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

———. “White-Robed Reformers: The Ku Klux Klan Comes to Arkansas 1921–1922.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 22 (Spring 1963): 8–23.

Arkansas Ku Klux Klan Materials. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Barnes, Kenneth C. “Another Look behind the Masks: The Ku Klux Klan in Bentonville, Arkansas, 1922–1926.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 76 (Autumn 2017): 191–217.

———. Anti-Catholicism in Arkansas: How Politicians, the Press, the Klan, and Religious Leaders Imagined an Enemy. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2016.

———. The Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Arkansas: How Protestant White Nationalism Came to Rule a State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2021.

———. “The Ku Klux Klan in Faulkner County, 1921–1924.” Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings 56 (Fall/Winter 2014): 20–39.

Blevins, Brooks R. “The Strike and the Still: Anti-Radical Violence and the Ku Klux Klan in the Ozarks.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Winter 1993): 405–425.

Conant, Eve. “Rebranding Hate in the Age of Obama.” Newsweek, May 4, 2009.

Cope, Graeme. “‘The Master Conspirator’ and His Henchmen: The KKK and the Labor Day Bombings of 1959.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 76 (Spring 2017): 49–67.

Deaton, Ron. “The Clark County Ku Klux Klan Debates of 1922–23.” Clark County Historical Journal (2015): 33–39.

Holley, Donald. “A Look behind the Masks: The 1920s Ku Klux Klan in Monticello, Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Summer 2001): 131–150.

Jackson, Kenneth T. The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915–1930. Chicago: Elephant Paperbacks, 1992.

Lancaster, Guy. “Many a Civil Monster: Lynching and the Ku Klux Klan in Hot Springs, 1922.” The Record (2019): 4.1–4.22.

MacLean, Nancy. Behind the Mask of Chivalry: The Making of the Second Ku Klux Klan. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

McVeigh, Rory. The Rise of the Ku Klux Klan: Right-Wing Movements and National Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Starbird, J. C. “Ku Klux Klan in Krawford Kounty.” The Heritage 21 (March 1978): 9–10.

Dianne Dentice

Stephen F. Austin State University

American Krusaders

American Krusaders Anti-Catholicism

Anti-Catholicism Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Hate Groups

Hate Groups Labor Movement

Labor Movement White Revolution

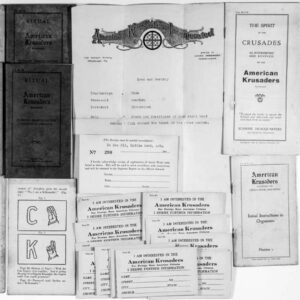

White Revolution American Krusaders Ephemera

American Krusaders Ephemera  AOUW Building

AOUW Building  The Arkansas Traveller

The Arkansas Traveller  The Arkansas Traveller

The Arkansas Traveller  Comer Article

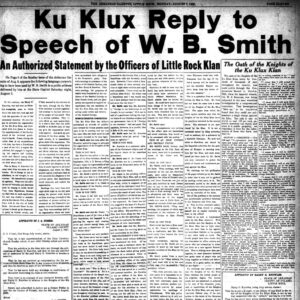

Comer Article  Comer Speech Response

Comer Speech Response  Robbie Gill Comer

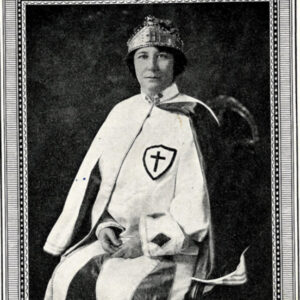

Robbie Gill Comer  Robbie Gill Comer

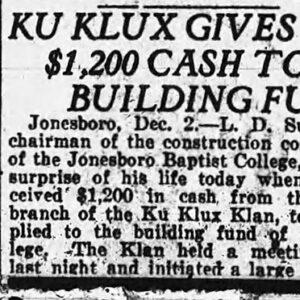

Robbie Gill Comer  KKK Donation

KKK Donation  KKK Press Release

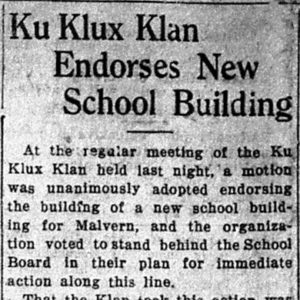

KKK Press Release  KKK School Endorsement Article

KKK School Endorsement Article  Klan Haven Orphanage

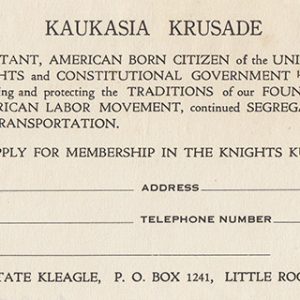

Klan Haven Orphanage  KKK Application

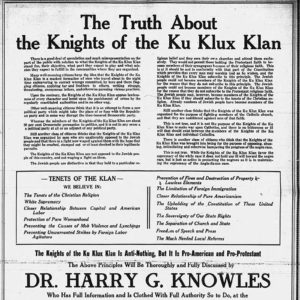

KKK Application  KKK Ad

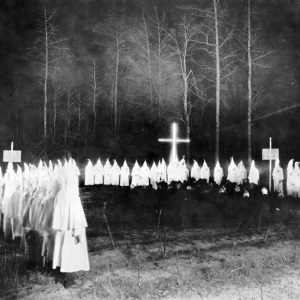

KKK Ad  Ku Klux Klan Rally

Ku Klux Klan Rally  Ku Klux Klan Rally

Ku Klux Klan Rally  William Frank Norrell

William Frank Norrell  WKKK Headquarters

WKKK Headquarters

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.