calsfoundation@cals.org

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School

The Walnut Ridge Army Flying School was one of seven U.S. Army Air Forces pilot training schools established in Arkansas as part of the nationwide expansion of World War II pilot training. Contract primary flying schools were located in Camden (Ouachita County), Helena (Phillips County), and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). Newport (Jackson County) and Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County) had basic flying schools, while Blytheville (Mississippi County) and Stuttgart (Arkansas County) had advanced twin-engine flying schools. The Walnut Ridge Army Flying School enrolled during its existence 5,310 students, 4,641 of whom graduated.

In early April 1942, a board of three army air forces officers—Lieutenant Colonel Burton Hovey Jr., Lieutenant Colonel John R. Cume Jr., and Captain Blanton Russell—went in search of a new location for an army air forces basic flying school. The site originally planned—in Dyersburg, Tennessee—was deemed unacceptable because it would require moving five million cubic yards of dirt. The three men flew over an area just northeast of Walnut Ridge that looked promising. Returning by car the next day, they looked over the site and checked on public schools, housing, utilities, and transportation. On April 15, 1942, they recommended it for the flight school. The U.S. government approved the recommendation, and construction on the Walnut Ridge Army Air Field began June 20, 1942.

The government paid $305,075 for 3,096 acres. The land housed private homes and the Moran School, a typical two-room rural public school. Forty-five families lived on the land and were forced to move out quickly; their homes were torn down. Landowners were paid an average of $110 an acre for their land, while the sharecroppers and tenant farmers who constituted most of those living on the land were reimbursed for a share of their crop.

To serve the new airfield, five auxiliary airfields were constructed, at Biggers (Randolph County), Pocahontas (Randolph County), Beech Grove (Greene County), Walcott (Greene County), and Bono (Craighead County), taking 2,624 acres of prime farmland. These other airfields were used for safety reasons. There were approximately 250 airplanes based on the field, and students did extensive take-off and landing practice; it would have been risky and impractical for that many airplanes to be in a traffic pattern at one time.

Construction of the airfield brought in 1,500 workers. Walnut Ridge and Pocahontas residents opened their homes to the workers. The mayors and the Boy Scouts worked to find housing for them. Churches and civic groups provided recreational facilities. Residents rented out rooms, garages, and attics to accommodate workers.

Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps units were assigned to several duty stations around Arkansas, including the Walnut Ridge Army Flying School.

Area unemployment had reached more than twenty-five percent during the Depression, but the airfield brought a new prosperity to Lawrence and Randolph counties. People who were once glad to get a dollar a day could make fifty cents to one dollar an hour or more at the airfield. They came from Jonesboro (Craighead County), Monette (Craighead County), Paragould (Greene County), the Ozark foothills, and southern Missouri.

The airfield was activated on August 15, 1942, with the arrival of the initial contingent of key military personnel. Ten days later, 100 troops arrived, but housing was not yet available at the airfield, so they were transported to and from the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp at Five Mile Spring north of Pocahontas for the first thirty days.

Even though the airfield was planned and designed as an army air forces basic flying school, for some time it appeared it would become an advanced glider school. As late as September 1942, preparations were being made for gliders.

Because of the delay in changing sites and the confusion over the glider program, the first three classes of aviation cadets set for Walnut Ridge went to the army airfield in Blytheville, which was being built as an advanced twin engine school. Blytheville was scarcely better prepared than Walnut Ridge. Circus tents were used for operations headquarters and classrooms. The runways were not ready, so flying was done from oil-coated dirt strips.

In late September, the Southeast Training Command, headquartered at Maxwell Field, Alabama, clarified the situation by announcing that twenty cadets from Camden and 102 cadets and three student officers from Decatur, Alabama, would be sent to Walnut Ridge for basic flight training, and the glider program was established at Stuttgart.

Training at Walnut Ridge began on October 12, 1942, and students began training on the BT-13. In less than two years, 5,310 students entered training, and 4,641 graduated. Forty-two students and instructors died in training. The last class graduated on June 27, 1944.

On September 1, 1944, the airfield was transferred to the Department of the Navy and operated as the Marine Corps Air Facility, Walnut Ridge. The marines trained only briefly, using SBD-5s and FG-1D Corsairs. Marine Attack Squadron 513 transferred from Oak Grove, North Carolina, to Walnut Ridge on September 14, 1944, and then moved to Mojave, California, on December 4, 1944. The facility was decommissioned on March 15, 1945.

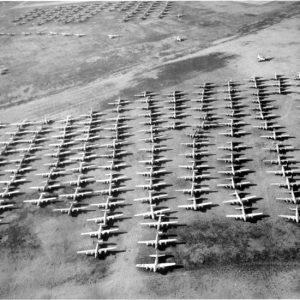

As the war ended, the U.S. Army Air Forces and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation revived the Walnut Ridge Army Air Field. With the war over, it seemed there would be no more need for so many military aircraft, and since the jet airplane had just been developed, many of them were considered obsolete. The government needed places to store and sell these planes. Six sites were selected—five for army air forces planes and one for navy and marine planes. Surplus sales were also conducted at several other much smaller facilities. Walnut Ridge was an ideal site because of the large land area and large parking ramp. The planes came in droves, with as many as 250 arriving in a single day. An estimated 10,000 to 11,000 warplanes were flown to Walnut Ridge in 1945 and 1946 for storage and sale. At least sixty-five of the military’s 118 B-32 heavy bombers were flown to Walnut Ridge, many straight from the assembly line.

In September 1946, the Texas Railway Equipment Company bought 4,871 of the aircraft stored at Walnut Ridge—primarily fighters and bombers—to scrap them. The bid price was $1,817,738. Two giant smelters were constructed to melt the scrap aluminum, which was formed into huge ingots for shipping. In about two years, the planes were all scrapped. When the salvage was completed, the air field proper, along with about sixty percent of the land, was turned over to the city of Walnut Ridge to be used as a public airport. All runways are still active in the twenty-first century, and one was extended to 6,000 feet.

The Walnut Ridge Army Flying School Museum was formed in 1999 to preserve the air field’s rich history. A documentary on the airfield’s history, Wings of Honor, was produced in 2005.

For additional information:

Green, Gwen. “Army Airfield Gave Walnut Ridge its Niche in World War II History.” Lawrence County Historical Journal 9 (Fall 2004): 5–7.

Hackworth, Bill. “History of the Walnut Ridge Army Airfield.” Lawrence County Historical Quarterly 8 (Fall 1985): 20–24.

Lawrence County Historical Society. Lawrence County, Arkansas: 1815–2001. Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 2001.

Walnut Ridge Army Air Field. http://www.walnutridgearmyairfield.com/ (accessed August 2, 2023).

Harold Johnson

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School Museum

Aviation

Aviation Military

Military Walnut Ridge Army Air Field

Walnut Ridge Army Air Field  Walnut Ridge Army Flying School

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School  Walnut Ridge Army Flying School

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School  Walnut Ridge Army Flying School B-32s

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School B-32s  Walnut Ridge Army Flying School BT-13

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School BT-13  Walnut Ridge Army Flying School Fighter Planes

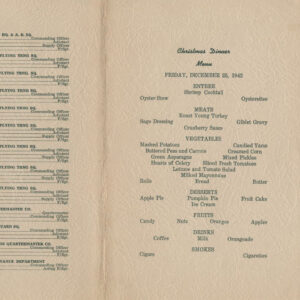

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School Fighter Planes  Walnut Ridge Flying School Menu

Walnut Ridge Flying School Menu

My father’s family lived in Tuckerman and were sharecroppers. My dad and my uncle used to tell stories of the pilots training there at the Walnut Ridge Army Flying School (my uncle was about eight at the time and my dad about twelve). They would go swimming/fishing to the Black River or White River and watch the pilots practice. They liked to see the low-flying pilots wave back to them while picking cotton. They were even the first (according to them) to run up on a crashed aircraft. Meeting a pilot was a boyhood highlight they still spoke about as adults, and it gave me a sense of history, eventually leading me to this site! Thanks for publishing!